It’s not as if the European Union needed to plan another landmine to explode the agreed “fiscal compact” from last December which, broadly speaking, would require EU countries to maintain a structural deficit of less than 0.5% of nominal GDP annually. ![]()

With the anti-austerity candidate leading the polls in France and with Greek parliamentary elections scheduled for the spring, there is no shortage of political events that could cause yet another crisis in the eurozone. And after so many countries (including Germany!) violated the 1997 Stability and Growth Pact’s budget deficit rule (no more than 3% of GDP) throughout the 2000s, you might remain skeptical that any country would hew for very long to a 0.5% budget rule.

So the last thing anyone in Brussels wanted to hear was Dublin’s insistence last week that the fiscal compact will require an Irish referendum prior to its ratification.

Yet last week, Irish Taoiseach Enda Kenny announced that, on advice from the Irish attorney general, Ireland will be required to hold a referendum on the fiscal compact treaty. It was previously thought (hoped?) that an Irish referendum might not be necessary. Given that British prime minister David Cameron announced that the UK would veto the amendment of existing EU treaties, and the decision of the Czech Republic not to join the final version, the treaty is not a formal EU treaty, but an intergovernmental treaty among the remaining 25 EU members.

Under Crotty v. An Taoiseach in 1987, the Supreme Court of Ireland decided that any significant changes to any EU treaties to which Ireland accedes require an amendment to the Irish constitution prior to ratification, and therefore subject to a referendum.

Currently, polls indicate that 60% of Irish voters support the treaty, but the referendum date has not yet been announced and opponents will have ample time to mobilize.

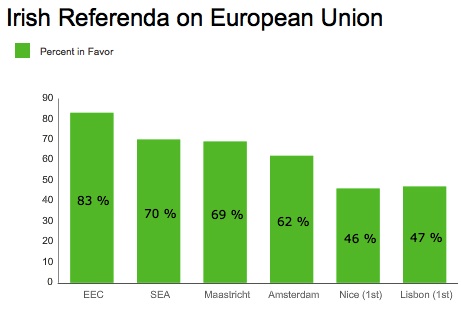

If you look at the trajectory of the first-shot Irish referenda on various EU treaties, you would not necessarily be optimistic:

- The first two referenda on the EU — the decision to join what was then the European Economic Community (May 1972) and the decision to enact the Single European Act (May 1987) — passed with very strong support: 83.1% and 69.9%, respectively.

- The next two referenda — approving the Maastricht Treaty (June 1992) on the single currency and the Treaty of Amsterdam (May 1998) also passed with strong, if slightly less, support: 69.1% and 61.7%, respectively.

- The next referendum in June 2001 on the Treaty of Nice was less successful. On a turnout of just 35%, fully 53.9% of voters rejected the treaty. After Ireland secured the Seville Declarations to the Treaty of Nice recognizing Ireland’s military neutrality, and after a much more vigorous campaign in favor of the treaty, the Irish electorate in March 2002 approved the treaty on a vote of 62.9%.

- While Ireland never held a vote on the EU constitution (French and Dutch voters stalled the momentum in rejecting the constitution in May and June 2005), it held a vote on the EU constitution’s successor, the Treaty of Lisbon. Again, in June 2008, Irish voters rejected the Lisbon Treaty by a 53.4% margin. Again, after Irish leaders secured further concessions in negotiation with EU leaders on the issues of national taxation, Irish neutrality, and other Irish constitutional provisions, Irish voters were given a second chance to “get it right,” and again, in October 2009, 67.1% of the Irish electorate approved the Lisbon Treaty.

In both the Nice and Lisbon cases it could be said that Irish voters were registering disapproval with national governments (especially in 2008, with voters none too pleased with personal finance scandals that had forced then-Taoiseach Bertie Ahern to resign). But increasingly, referenda have been seen as an opportunity for Irish voters to voice their disapproval with the recent direction of the European unification project.

Given past practice with both Nice and Lisbon, there’s also now a moral hazard and a hold-up problem for the EU — because Irish will hold the only referendum on the treaty, Irish voters have every incentive to vote down the treaty initially to force Irish leaders to drive a harder bargain. Sure enough, a EU bureaucrat yesterday noted that the Irish are now known for a tendency to vote twice, even if Kenny is promising that this will be a one-time-only referendum.

The stakes could not be higher. On one hand, an Irish “no” vote could send markets reeling at an intergovernmental EU apparatus that is only as strong as its weakest link.

On the other hand, an Irish “no” vote could also cause significant blowback for Ireland. It could endanger future bailouts for Ireland, whose government assumed the debts of Irish banks that collapsed in 2008, leading Ireland into the headwinds of a continent-wide sovereign debt crisis and necessitating an EU bailout in late 2010. At worst, it could even lead to Ireland’s withdrawal from the euro.

So how is the Irish political landscape shaping up?

Kenny, who leads the center-right Fine Gail party, will support the treaty, as well as his coalition ally, the more leftist Labor Party.

Éamon Ó Cuív, the deputy leader of the opposition Fianna Fáil, the centrist party that has held power most often in Ireland’s post-independence history, has resigned as deputy leader and party spokesman on communications, energy and natural resources because he opposes the treaty. Micheál Martin, the Fianna Fáil leader, however, has announced the party’s support for the treaty.

Meanwhile, Gerry Adams, the leader of the republican Sinn Féin party, has denounced the treaty as an austerity straightjacket, arguing that it runs counter to Irish republicanism. Socialist Party TD Joe Higgins called the government ‘treasonous’ today for trying to frighten the public into a yes vote. So while no organized movement — like 2008’s Libertas movement — has emerged to oppose the treaty yet, there’s still time and opportunity.

Yes, but, Kevin, this new agreement doesn't have to be passed unanimously, right? So are you sure you're not exaggerating the effect of a referendum defeat?