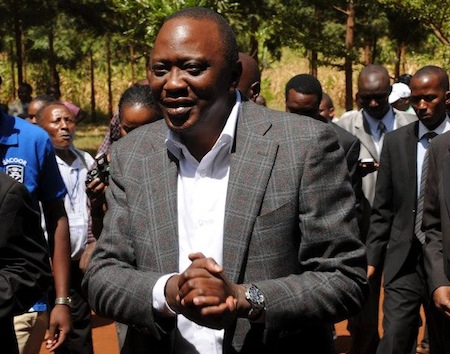

UPDATE: Kenyan president Uhuru Kenyatta has made a statement about today’s assault on Nairobi’s Westgate Mall, which has killed 39 people. Declaring terrorism a ‘philosophy of cowards,’ and declaring Kenya will respond in a manner ‘as brave and invincible as the lions on our coats of arms,’ Kenyatta responded with grace, strength and compassion, rallying the unity of the Kenyan people.

The despicable perpetrators of this cowardly act hoped to intimidate, divide and cause despondency among Kenyans. They would like us to retreat into a closed, fearful and fractured society where trust, unity and enterprise are difficult to muster. An open and united country is a threat to evildoers everywhere.

It’s worth watching in full:

* * * * *

Today’s attack on Nairobi’s Westgate Mall — perhaps the deadliest terrorist attack in Kenya since the 1998 assault on the US embassy in Nairobi — is the first crisis of the nascent presidency of Uhuru Kenyatta.![]()

![]()

![]()

Al-Shabab, the Somali militant group, has taken responsibility for the attack. The assailants, who attacked the mall with a combination of machine guns and grenades, may have killed over 30 people and injured many more. It’s not the first time the radical Somali group has threatened Kenya — and it follows an al-Shabab attack in July 2010 in Kampala, Uganda, that killed 74 people within a peaceful crowd that had gathered to watch the 2010 World Cup finals.

Al-Shabab’s rationale lies in the Kenyan invasion of Jubaland, the semi-autonomous tract of southern Somalia, in October 2011 and its subsequent role as part of an African Union peacekeeping force in Somalia. But the sudden attack on a shopping mall full of civilians — including expatriates, women and children — is a senseless and asymmetrical act of terrorism.

Even as we remember the victims of today’s tragedy and even as our thoughts remain with Nairobi police, Kenya Defense Force officials and hospital and health care workers carrying out rescue and recovery efforts, Kenyan policymakers face some weighty and difficult days ahead.

Kenyatta (pictured above, left) wasn’t president at the time of Kenya’s initial invasion, and he didn’t ask for this conflict when he was elected in March 2013 as Kenya’s fourth post-independence president.

But the challenge is his first serious crisis as president. That’s not to say that the challenges of boosting Kenya’s economy or maintaining the calm and orderly process of sorting out land reform in Kenya. But Kenyatta’s response to the Westgate killings places the Somali question at the heart of his administration, even amid signs that Somalia’s central government based in Mogadishu, with strong support from the African Union and Western governments, is making tentative strides (at least compared to more than two decades of civil war and state failure following the fall of strongman Mohamed Siad Barre in 1991).

It’s not an enviable position for Kenyatta.

If Kenyatta withdraws into what has been the traditional comfort zone of Kenya’s military and civilian leadership, it will mean that the most powerful (and still, even after today, by far the most stable) east African country is backing away from its vital role in solving east Africa’s most pressing regional security challenge. But if Kenyatta launches a hasty, retributive wave into southern Somalia in the weeks or months ahead, he could also risk drawing Kenyans further into a quagmire — with the possibility of future al-Shabab terrorist attacks within Kenya. Striking the right balance will be crucial.

Continue reading Westgate Mall siege the first test of Uhuru Kenyatta’s mettle as Kenya’s new president

Continue reading Westgate Mall siege the first test of Uhuru Kenyatta’s mettle as Kenya’s new president