For all the comparisons to Greece’s debt crisis, there’s one simple solution that many Puerto Ricans and mainland policymakers are prescribing to solve the commonwealth’s own financial crisis — and it’s not available to Greece or any other eurozone members. ![]()

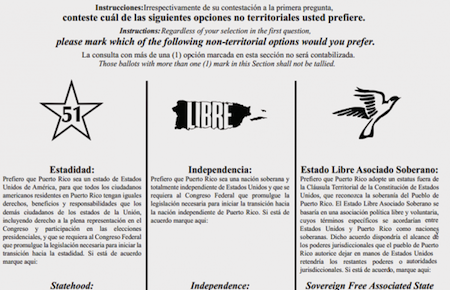

Puerto Rico could simply become the 51st American state.

For the past 63 years, it’s been an estado libre asociado — a self-governing commonwealth that lies uncomfortably between a state and a territory, with bespoke elements unique to Puerto Rico, both good and bad.

Republican presidential contender and former Florida governor Jeb Bush supports statehood and in 2012, both US president Barack Obama and his rival, former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney said they would support it if a clear majority of Puerto Ricans want statehood — Puerto Rico held a status referendum in the same election year. Pedro Pierluisi, Puerto Rico’s Democratic-affiliated non-voting delegate to the US House of Representatives, made the case for it in an op-ed in The New York Times earlier this month.

* * * * *

RELATED: The next debt crisis in the United States may

require a Puerto Rico bailout

RELATED: Could Puerto Rico really become the 51st US state?

* * * * *

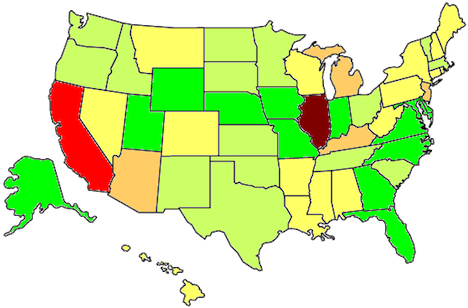

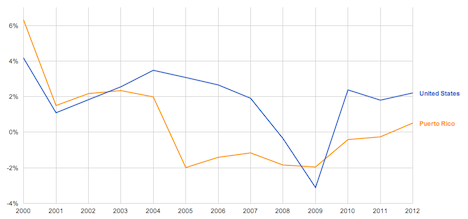

It’s true that both the Greek and Puerto Rican crises share much in common. Both governments are tethered to monetary policies that aren’t necessarily optimal. Functionally, that means neither Athens nor San Juan have a currency that they can depreciate to spur exports. Neither the European Central Bank nor the Federal Reserve can realistically be expected to tailor monetary policies to local needs. That, in turn, has exacerbated the effects from the economic forces of the past decade — the 2008-09 subprime crisis in the United States and the 2009-10 sovereign debt crisis in Europe, along with the economic pain of a nearly decade-long recession, rounds of tax increases and spending cuts, and accompanying rises in unemployment and downward pressure on wages. Lower growth, of course, means lower revenues and higher budget deficits — and more borrowing means higher yields that are now sucking Puerto Rico into a downward spiral. Alejandro García Padilla, its governor, made clear in late June that he believes the island’s $72 billion in debt is unsustainable.

In both scenarios, Greeks (through the Schengen zone) and Puerto Ricans (through the universal grant of US citizenship made in 1917 to allow Puerto Ricans to fight in World War I) can relocate to more economically prosperous European and American regions with ease. Migration means that fewer Puerto Ricans are left to service the growing debt — or build businesses and communities that can provide the revenues to fund schools and infrastructure. The island’s population is creeping downward; from a peak of 3.83 million in 2004, it was down to just 3.55 million last year. The pace of emigration is rising — to about 50,000 annually.

There are key differences as well between Greece and Puerto Rico.

Puerto Rico’s status is a relic of the late colonial era, and the United States acquired the island in 1898 as a result of its war against Spain (in Cuba, the Philippines and elsewhere). From the beginning, full-fledged independence has never been a popular option among Puerto Ricans. But nationalist sentiment rose so strongly by 1950 that two pro-sovereignty activists, Oscar Collazo and Griselio Torresola, attempted to assassinate US president Harry Truman.

The US policy response, Operation Bootstrap, adopted throughout the following decade to industrialize the island, transformed Puerto Rico into a more modern, urban place, even as American businesses consolidated the island’s farmland. But it never whisked Puerto Rico into a miraculous Caribbean Singapore, and it decimated small-scale agriculture.

Puerto Rico also suffers from the classic ‘island effect’ that economists sometimes describe of countries where dependence on imports and higher transport costs artificially increase the cost of living — a condition that’s often found throughout the Caribbean and islands, but that also affects Israel, a country surrounded by hostile Arab states with virtually no cross-border trade.

Most important of all, there’s no real talk of ‘PRexit,’ because no one believes that Puerto Rico could just abandon the ‘dollarzone.’ There’s no plan sitting in US treasury secretary Jack Lew’s desk that outlines the potential steps because it’s so much more implausible than a ‘Grexit.’

García Padilla is right that the crisis, decades in the making, is due to political factors as well as economic. Default may come soon — the Puerto Rican government says it doesn’t have enough cash to make a scheduled August 1 payment of nearly $170 million. That could launch a messy years-long default process, with the island trying to force haircuts on its bondholders. If San Juan can’t demand debt relief, protracted litigation might result in court rulings forcing Puerto Rico’s government to prioritize creditors over the salaries of public servants — galvanizing so much economic suffering that it would draw international condemnation over America’s neocolonial version of Greece.

There’s no effective Chapter 9 process for Puerto Rico, unlike for US municipalities, so the alternative of an orderly Detroit-style restructuring, isn’t available. The Obama administration, moreover, has made it clear that it doesn’t support a bailout — and it’s not clear that Republicans in Congress would be willing to provide the funds for any bailout.

So calls for statehood, in both Puerto Rico and on the mainland, and on the left and right, are on the rise, and predictably so. But as genuine as those calls might be, it’s a very, very unlikely result– and that will likely be true for a long time.

Here’s why. Continue reading Four reasons why Puerto Rico won’t become a state anytime soon