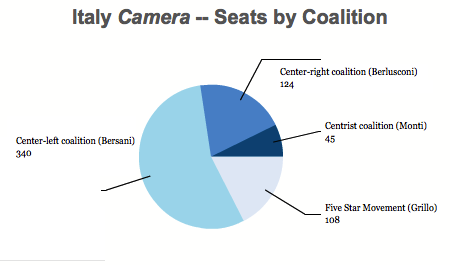

With the failure of centrosinistra (center-left) leader Pier Luigi Bersani to form a government after a week of talks, Italian president Giorgio Napolitano now faces a tough 24 hours of consultations with the other key players in the Italian parliament.![]()

The path now becomes perilous — for Napolitano, above all, who remains just about the only respected public official left in Italy:

- Of course, as I noted earlier today, upon further consultation with the various players on Friday, Napolitano could give Bersani, the leader of the Partito Democratico (PD, Democratic Party), more time to cobble together a government. That doesn’t seem so incredibly likely to succeed.

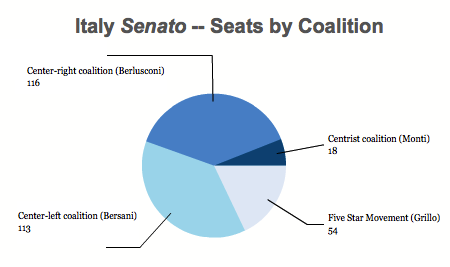

- Napolitano could also appoint Bersani as prime minister to try to win a vote of confidence in the upper house of the Senato, essentially daring Silvio Berlusconi’s centrodestra (center-right) coalition to reject him, though it seems unlikely that Napolitano would do so if there’s a chance Bersani would lose the vote. If Bersani loses, he’ll be left as a discredited caretaker prime minister, and Napolitano will have suffered a political defeat as well, limiting his future maneuverability.

- Another option is simply to leave prime minister Mario Monti (pictured above shaking hands with Italian senator Emma Bonino) in place as a pro forma caretaker — this is the ‘Belgian’ option: a parliament with no real government. That could well cause Italian bond yields to rise or otherwise call into question Italy’s capability for long-term reform. That’s especially true if you think the eurozone is primarily a political crisis rather than an economic one.

Another option, of course, would be for Napolitano to appoint a new technocratic prime minister, though that carries risks as well, especially coming after the political rejection of Monti’s pro-reform, centrist coalition in the February elections. Monti was appointed as a technocratic prime minister in November 2011 with the support of both the PD and Berlusconi’s Popolo della Libertà (PdL, People of Freedom). In late 2011 and early 2012, Monti’s government instituted reforms to reduce tax evasion, increased taxes, pension reform that reduces early retirement, and he instituted some modest labor reforms as well, though they’ve not had the sweeping effect Italy’s economy may need to revitalize its labor market.

But Monti’s government stalled and Italy went to early elections in February when Berlusconi and the PdL pulled its support from Monti’s government, and Berlusconi and Beppe Grillo, leading the protest Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S, the Five Star Movement) actively ran against Monti’s reforms and attacked Monti as little more than an errand-boy for Brussels and Berlin.

So if neither Bersani nor Monti appear workable choices, to whom could Napolitano turn in the event of yet another technocratic government? Such a government would have a very limited mandate for, say, electing a new president (which the new parliament must accomplish in May 2013 before new snap elections could even be held), carrying out the execution of Italy’s 2013 budget and perhaps even overseeing a change in the election law.

Here are seven potential candidates to keep an eye on in the days ahead: Continue reading Seven people who could be appointed Italy’s next technocratic prime minister