A surprisingly tighter race than expected for Argentina’s presidency is making it more likely that frontrunner Daniel Scioli will win outright in the first round on Sunday, October 25.![]()

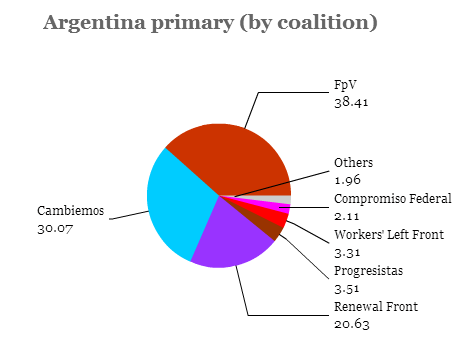

Back in August, Scioli, the outgoing governor of Buenos Aires province and the presidential nominee of outgoing president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and the governing Frente para la Victoria (FpV, the Front for Victory), demonstrated his strength by winning around 38.5% of the vote in Argentina’s somewhat unique ‘open primary’ contest.

His nearest contender was Mauricio Macri, the more conservative and economically liberal outgoing mayor of Buenos Aires, who is leading a broad center-right coalition called Cambiemos (which loosely translates as “Let’s change”), which won about 30% of the vote (including the other challengers who competed with Macri for the coalition’s presidential nomination).

Far back in third place was Sergio Massa, one of Kircher’s first cabinet chiefs, now the mayor of Tigre and the leader of an alternative peronista group, the Frente Renovador (FR, Renewal Front), which won just 20.5% of the vote.

* * * * *

RELATED: Kirchner 2019 comeback could

complicate Scioli presidential bid

RELATED: Scioli leads in Argentine presidential race after primaries

* * * * *

A one-time frontrunner after leading his new group to the top result in Buenos Aires province during the 2013 midterm elections, Massa’s appeal seems to have stalled through 2014 and earlier in 2015. His electoral alliance choices turned out to be weaker than expected, and he lacks the voter base that both Scioli (as leader of Argentina’s most populous province) and Macri (as leader of Argentina’s capital city) can boast. Moreover, as Kirchner’s approval ratings improved over the course of 2015, so did Scioli’s standing, as he won back disaffected peronistas who might otherwise be tempted to join Massa’s alternative group.

Since August, Scioli continues to lead the pack, while the movement in the race has come in the battle for second place — most polls are now showing that Macri is losing votes and that Massa is gaining. There are many potential reasons.

Explaining the Massa popularity surge

It could be that Argentines feel that Macri is still too close, ideologically speaking, to the economic neoliberalism of the 1990s that many voters feel was responsible for destroying the economy in 1999-2001.

It could be that Macri has been tarred by association with Fernando Niembro, a businessman who had been one of the coalition’s leading congressional candidates from Buenos Aires until suspending his campaign in September following an indictment on money laundering charges. That connection has made it hard to argue that Macri will make doing business in Argentina more efficient, transparent or graft-free.

It could be that Macri has done so much to signal that he will not introduce radical change that voters are doubting his authenticity, ability or resolve. He’s already pledged not to re-privatize the Argentine state oil company, YPF, or the airline company Aerolíneas Argentinas. If there’s one thing that Macri is not, it’s a peronista. But he has spent much of the post-primary period embracing peronismo. Earlier this month, Macri even unveiled a new statue of Juan Perón in the capital, awkwardly arguing that he shared the values of peronismo:

“I am not a Peronist but I have social justice in my heart,” Macri said as he unveiled the statue of Peron last week. “I want to invite all Peronists to work with us to create the Argentina we all dream about.”

But Massa’s improvements could also come from a belief that Massa represents a better chance for gradual ‘change,’ with a better shot of defeating Scioli if the race continues to a runoff on November 22. There are still real doubts about Scioli’s ability to run an independent administration with so many Kirchner loyalists in key positions, including the vice presidency. Continue reading Tactical voting considerations cloud outcome of Argentine presidential election