As widely expected, Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party of Japan (LDP, or 自由民主党, Jiyū-Minshutō) surged to an overwhelming victory in Sunday’s national elections in Japan to determine half of the seats (121) in the House of Councillors, the upper house of the Diet (国会). While the victory wasn’t enough to give the LDP a two-thirds supermajority in both houses of the Diet, it was enough to usher in a new era of continuity, with the government of prime minister Shinzō Abe (安倍 晋三) set to consolidate power after winning election in the lower house, the House of Representatives, last December.![]()

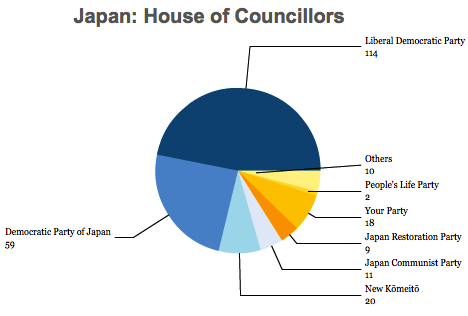

The result leaves the LDP, together with its ally, the Buddhist conservative New Kōmeitō (公明党, Shin Kōmeitō) with a majority in the upper house, and that will give the LDP the ability to push through legislation without needing to compromise in the House of Councillors and it makes Abe the strongest Japanese prime minister since Junichiro Koizumi (小泉 純一郎) in the early 2000s and ends a seven-month period of a ‘twisted Diet,’ with control of the upper house still in the hands of the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ, or 民主党, Minshutō).

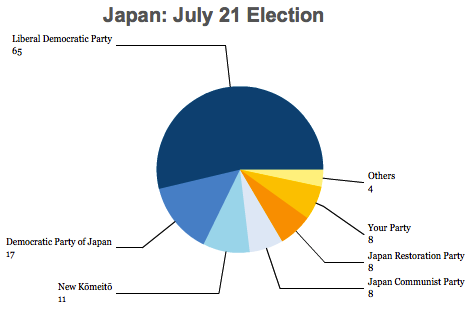

But the LDP looked set to fall just below an absolute majority in its own right:

In contrast, the LDP holds 294 seats in the 480-seat House of Representatives, and together with the 31 seats of New Kōmeitō, holds a two-thirds majority. That the LDP doesn’t hold an equally impressive advantage in the upper house is due to the fact that only half of the seats in the House of Councillors were up for election yesterday and, among those 121 seats, the LDP’s dominance is clear:

That also means that the Democratic Party doesn’t face an immediate wipeout, and it will remain the chief opposition party — in fact, their 59 seats in the House of Councillors is actually more than the 57 seats they currently hold in the House of Representatives. That will give the DPJ a legislative base from which it can attempt to rebuild itself as a political force and to position itself for 2016, when Japan’s next elections are likely to come. Banri Kaieda, a fiscal hawk who assumed the party’s leadership after its December 2012 defeat, will stay on for now as leader.

But the Democrats weren’t the only losers on Saturday. It was perhaps an even more difficult election for the Japan Restoration Party (日本維新の会, Nippon Ishin no Kai). A merger between the two smaller parties of Osaka mayor Tōru Hashimoto (橋下徹) and right-wing, nationalist former Tokyo governor Shintaro Ishihara (石原慎太郎), it emerged with 54 seats in the House of Representatives in December to become as the third-largest party. But it won just eight seats on Saturday, and the party now seems likely to split up. That’s largely due to Hashimoto’s awkward comments suggesting U.S. soldiers in Okinawa should be permitted to use prostitutes and controversial comments that largely defended the ‘comfort women’ system, whereby Japanese soldiers forced women in enemy countries to serve as sexual slaves. But it’s also due to the fact that nationalist tensions stemming from a standoff with the People’s Republic of China over the Senkaku Islands (Diaoyu Islands in Chinese) have calmed somewhat since last December.

One success story was the Japanese Communist Party (JCP, or 日本共産党, Nihon Kyōsan-tō), which won eight seats on Saturday, bringing its total to 11. Founded in 1922, the JCP has not been a strong force in recent years. Though it has left its Marxist roots in the past, it has gained a modest amount of strength since the 2008 global financial crisis and it supports ending Japan’s military alliance with the United States.

But beyond the horse-race dynamics of Saturday’s result, what can we expect from Japanese policy in the next three years? Here’s a look at eight key issues that are likely to dominate the LDP’s agenda, at least in the near future. Continue reading Quivering for the fourth arrow of Abenomics (and other Japanese policy matters)