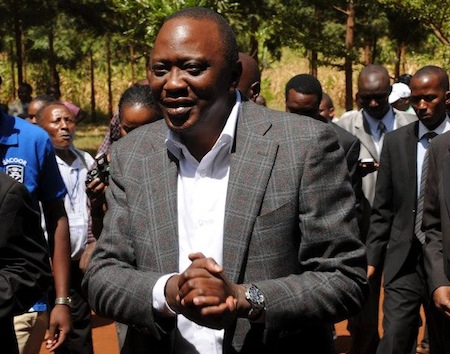

With all constituencies now in, Uhuru Kenyatta has been elected the fourth president of Kenya with 50.03% of the vote, triumphing over prime minister Raila Odinga, who won 43.28%, avoiding an April runoff by just 4,099 votes.

Kenyatta is the son of Kenya’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta, and is the candidate of the Jubilee coalition, an alliance of parties featuring mostly Kenyans of Kenyatta’s own Kikuyu ethnic group and the Kalenjin ethnic group of his running mate, William Ruto, who will now become vice president. Kenyatta ran for president — and lost by a wide margin — in 2002 to the outgoing president, Mwai Kibaki. He served briefly in the current government as finance minister from 2009 to 2012.

Odinga, the son of Kenya’s first vice president, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, was the runner-up in the 2007 presidential election that was widely believed to have been fraudulent. Following the post-election tumult, Odinga was appointed prime minister in 2008 in a power-sharing agreement with Kibaki. He was the candidate of the Coalition for Reforms and Democracy (CORD) alliance, comprise of Odinga’s Luo ethnic group and other ethnic groups.

What comes next?

The International Elections and Boundaries Commission is set to meet early Saturday morning, Nairobi time, to audit the results and announce an official winner.

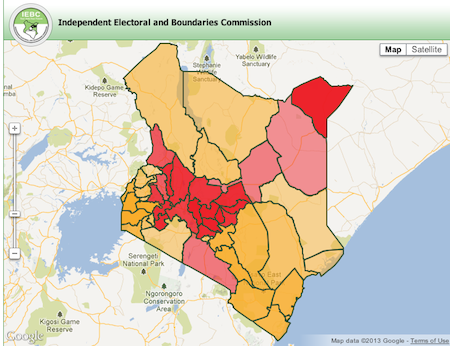

First off, provided that this count stands (and it’s the final count, not the provisional count, so it should, pending a court challenge from Odinga), Kenyatta needs to strike a tone of unity to avoid any chance of a repeat of the violence that followed the previous election. There’s not much of a hint that violence will erupt, but 50.03% is an incredibly narrow margin, Odinga’s Luo ethnic group will be unhappy to have been shut out once again from power, and it’s clear that Kenya remains very much split on ethnic lines in terms of governance. Nonetheless, there are a lot of reasons why, this time around, Kenya is unlikely to repeat anything like what happened in 2007-08.

Secondly, it appears that Kenya will avoid anything similar to the power-sharing of the last five years, with the Jubilee coalition set to take control of both houses of Kenya’s parliament. Under a new constitution adopted in 2010, Kenya will have for the first time a bicameral parliament, with both a National Assembly and a Senate, each of which has allotted a set number of seats particularly for women.

Thirdly, there’s the matter of an indictment of each of Kenyatta and Ruto for crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Court and the awkward position of Kenya’s head of state accused of atrocities pending trial in The Hague. Governments in Europe and the United States will need to find a way to work with Kenyetta, though, because Kenya, with 40 million people, and a relatively stable nation, is a key regional partner for all sorts of strategic, humanitarian and economic purposes. The next hearing for Kenyatta, however, was postponed until June, and given the relative weakness of the case, there’s a chance prosecutors may simply drop the case altogether.

Finally, of course, there’s the matter of governing Kenya — Kenya faces sluggish growth and high unemployment, especially among its explosively robust young population, and that will (or should) certainly be at the top of Kenyatta’s governing agenda. Corruption should come a close second, and the joke is that Kenyatta, thought to be the richest man in Kenya, is so wealthy that he’s particularly immune to corruption.

Kenyatta will also oversee the continuation of reforms that began under Kenya’s new 2010 constitution, including the coordination of the Independent Land Commission and its recommendations for sorting out the mess of land ownership in Kenya and determining the best economic use for land with no titles — or too many titles. He will also sort out the minor issues that arise from devolution — under the 2010 constitution, Monday’s elections also saw each of Kenya’s newly drawn 47 counties elect their own governors and county-wide assemblies.