After Iceland’s election last month, I pointed to a trend in European politics that I called the European three-step, which goes something like this:![]()

- Left-wing government presides over initial economic collapse in 2008-09 in aftermath of global financial crisis

- Right-wing government defeats leftists in election, only to preside over more painful economic effects of eurozone crisis, continued European recession and painful budget cuts and tax increases.

- Left-wing government returns back to power in second election despite unenthusiastic electorate that has begun looking for more radical alternatives.

That pattern doesn’t exactly fit what happened in Bulgaria’s election over the weekend, but it comes fairly close:

So after blazing into office after the July 2009 elections with a landslide victory, prime minister Boyko Borissov and his center-right Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB, Граждани за европейско развитие на България) clawed their way to a narrow plurality of the vote over former Sergei Stanishev and the center-left Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP, Българска социалистическа партия), which governed from 2005 to 2009.

So after blazing into office after the July 2009 elections with a landslide victory, prime minister Boyko Borissov and his center-right Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB, Граждани за европейско развитие на България) clawed their way to a narrow plurality of the vote over former Sergei Stanishev and the center-left Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP, Българска социалистическа партия), which governed from 2005 to 2009.

Bulgaria’s electorate turned out in lower numbers than at any time since Bulgaria emerged from the Iron Curtain in 1989.

Maybe that’s fitting, because Bulgaria’s electorate is also smaller than at any time since the 1980s — its 7.5 million population has dropped by about 1.5 million people in the past quarter century. Bulgaria’s actually in decent fiscal shape for the time being — its public debt is low (only about 18% of GDP) and its budget deficit is below 2% of GDP. But in just about every other way, Bulgaria is in deep trouble.

As a perennial contender with Romania as the poorest nation in the European Union, Bulgaria’s shrinking population, rising unemployment, flatline GDP growth (the economy just barely grew in 2012) and rising energy costs have left Bulgarians suffering some of the worst effects of Europe’s ongoing recession. A wiretapping and eavesdropping scandal had already plagued Borissov’s government throughout the campaign before the discovery of 350,000 fake ballots in the lead-up to the election that have also left Bulgarians with little confidence in either major party to address what amounts to an existential challenge for Bulgaria.

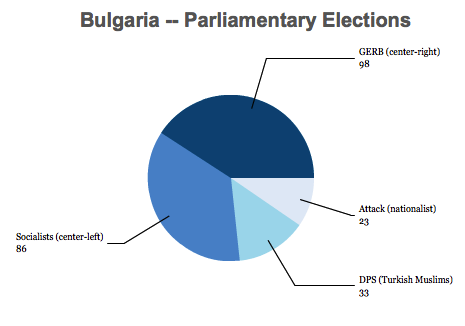

GERB won 30.53% of the vote to just 26.65% for the Bulgarian Socialists, which translates into 12 greater seats for GERB than the Bulgarian Socialists (98 to 86), but it’s a far cry from the 22% gap between the two parties that had left GERB with a nearly three-to-one advantage (117 to 40) in Bulgaria’s 240-seat, unicameral National Assembly (Народно събрание).

Although GERB will technically be the largest bloc in the National Assembly, Stanishev (pictured above) seems likely to return as prime minister in a coalition with the third-largest party, the Movement for Rights and Freedoms (DPS: Движение за права и свободи), an economically liberal party that represents ethnic Turks and other Muslims and that has indicated it would support the Bulgarian Socialists. Together, however, the two parties would have just 119 seats, two short of a majority.

That’s because GERB is unlikely to be able to govern on its own, and it’s loathe to form a coalition with Attack (Политическа партия Атака) is a far-right, anti-European nationalist party. Despite the horrid economic conditions in Bulgaria, though, support for Attack actually dropped since 2009 from about 9.4% to 7.3%, though it gained two seats for a total of 23 after Sunday’s election. Together, GERB and Attack would only command a bare one-vote majority, and Borissov would likely prefer new elections than to govern in a weak coalition with a noxious far-right partner like Attack.

GERB and the Bulgarian Socialists have ruled out a ‘grand coalition’ between the two of them, and the DPS has ruled out any kind of coalition with Attack, which makes sense given Attack’s virulent anti-Turk and anti-Roma positions.

But that doesn’t mean that Stanishev can’t find a couple of votes from GERB, perhaps, to push him into office, at least for a short while. Otherwise, new elections are all but inevitable, though it’s unclear what exactly a new round of elections would mean for Bulgaria’s policy options.

Given that Bulgaria still uses the lev and not the euro, the silver lining is that Bulgaria’s political turmoil won’t spin off yet another cardiac-clenching eurozone crisis moment. But Europe nonetheless should be quite concerned, especially in light of the erosion of nascent legal and democratic institutions in nearby Hungary and Romania.