When elections were called in Italy late in 2012, the centrosinistra (center-left) coalition united around Pier Luigi Bersani thought, on the basis of polls that showed Bersani (pictured above, left) with a wide lead, that it was nearly assured that they would easily win a five-year mandate to govern Italy.![]()

Instead, they may have won just a five-day mandate to show that they can win a confidence vote in both houses of Italy’s parliament.

The leader of Italy’s Partito Democratico (PD, Democratic Party), Pier Luigi Bersani, will have the first formal opportunity to form a government after three days of talks between Italy’s president Giorgio Napolitano (pictured above, right) and the various party leaders, including former technocratic prime minister Mario Monti, who ran on a platform of extending his reform program; former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi, whose centrodestra (center-right) coalition nearly outpaced Bersani’s coalition; and Beppe Grillo, the leader of the Movimento 5 Stelle (the Five Star Movement), who himself did not run for a seat in the Italian parliament.

Napolitano, in a rare speech today, pleaded for a solution, arguing that institutional stability is just as important as financial stability.

Yesterday, Bersani called for a grand ‘governo di cambiamento,’ a government of change that would draw from all of the parties in the parliament. It’s not immediately clear, however, what exactly Bersani would do with such a government or that the announcement would significantly shake up the coalition talks.

Bersani will have until March 26 — Tuesday — to show that he can pull together a patchwork vote of confidence. Otherwise, Napolitano will conduct further talks with the party leaders in search of a Plan B.

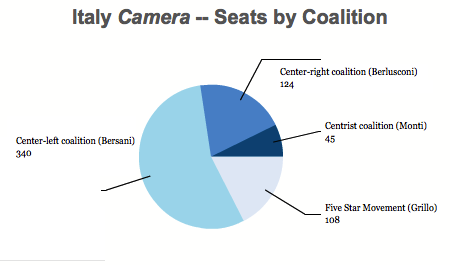

In the February 2013 elections, the centrosinistra won an absolute majority of the seats in the 630-member Camera dei Deputati (House of Deputies) because under Italian election law, the winner, by whatever margin, of the nationwide vote automatically wins 54% of the seats. So Bersani commands a majority in the lower house, though he does so after winning a surprisingly narrow victory (29.54%) over Berlusconi’s centrodestra (29.18%) and Grillo’s Five Star Movement (25.55%):

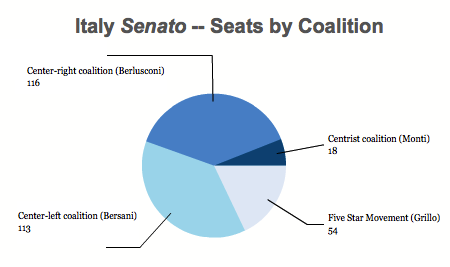

The current crisis of governance in Italy springs from the fact that there’s no similar ‘national winner’s bonus’ for the upper house, the Senato, where the centrodestra actually won more seats than the centrosinistra. That’s because there’s a regional ‘bonus’ — the party with the most support in each of Italy’s 20 regions is guaranteed an absolute majority of the senatorial seats in that region. As Berlusconi’s coalition won so many of the contests in Italy’s largest regions (i.e., Piedmont, Sicily, Campania), however narrowly, he won the largest bloc in the Senato:

In the immediate aftermath of the election results, I argued that Italy faced essentially four paths for a government:

- A Bersani-Monti minority government.

- A Berlusconi-Bersani ‘grand coalition.’

- A formal or informal Bersani-Grillo alliance.

- Snap elections (after the election of a new president).

Since then, we haven’t seen an incredible amount of action, because the parliament only sat for the first time last weekend, when it elected speakers to both the lower and upper houses. None of those are likely to happen in any meaningful sense, but there are small variations on each that could keep Italy’s government moving forward, if only for a short-term basis to implement a narrow set of reforms (e.g., a new election law) and to elect a new president — Napolitano’s term ends in May.

So with the clock ticking for Bersani’s chances of becoming prime minister and leading a government, where do each of those options still stand? Continue reading Pier Luigi Bersani has five days to build an Italian government