It was always a stretch to believe that there was enough room in France’s government for both Arnaud Montebourg and Manuel Valls.![]()

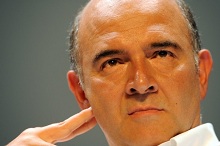

Montebourg, who represents the unapologetically socialist wing of France’s Parti socialiste (PS, Socialist Party), received a promotion in April as economy minister when French president François Hollande reshuffled his cabinet and replaced former prime minister Jean-Marc Ayrault with Valls. At the time, it was hardly clear that Montebourg deserved it after picking fights with prominent foreign businessmen in both the United States and India and waging an avowedly protectionist ‘Made in France’ campaign while serving as minister for industrial renewal. Montebourg (pictured above), with a charming grin, trim figure and a wavy swath of dark hair, who last weekend shared a photo of Loire Valley red wine on his Facebook feed, fits neatly into the American stereotype of the preening, tiresome, French socialist.

* * * * *

RELATED: Who is Manuel Valls? Meet France’s new prime minister

RELATED: Sapin, Royal, Montebourg headline new French cabinet

* * * * *

Valls, meanwhile, is leading Hollande’s government at a time when the Socialist administration is turning even more to the center, with a much-heraled (if hokey) ‘Responsibility Pact’ that aims to cajole French businesses into hiring a half-million new workers with the promise of a €40 billion payroll tax cut, financed by an even greater €50 billion in spending cuts. Though he’s regularly touted as a reformer, it’s more accurate to say that the Spanish-born Valls is a tough-minded ‘third way’ centrist who wants to rename the Socialist Party, which he considers too leftist. As interior minister, he showed he could be just as tough on immigration and crime as former conservative president Nicolas Sarkozy. When he became as prime minister in late March, Valls had the highest approval rating by far of any cabinet member. Today, his approval is sinking fast — an IFOP poll last weekend gave Hollande a 17% approval rating and Valls just 36% approval.

But Valls always had the support of Hollande and allies like finance minister Michael Sapin, and it was clear even in the spring that Montebourg was destined to become more isolated than ever in the Valls era.

It took less than five months for the cabinet to rupture. Montebourg publicly challenged Hollande over the weekend to rethink his economic policy in light of new data that show France’s economy remains stagnant — growing by just 0.1% in the last quarter, far below Hollande’s already-anemic target of 1%. Montebourg has also criticized Germany for encouraging austerity policies throughout the eurozone that he and other left-wing European politicians and economists blame for weakening the continent’s economic growth since the 2008-09 financial crisis.

In response, Valls orchestrating a dramatic resignation on Monday morning, though Hollande has given him a mandate to form a new government that won’t include Montebourg or allies like education minister Benoît Hamon and culture minister Aurelie Filippetti.

The drama surrounding this week’s reshuffle is hardly welcome so soon after Valls’s initial appointment, and Hollande risks a wider revolt on the French left that could endanger his agenda in the Assemblée nationale (National Assembly), where Socialist rebels could join legislators from the center-right Union pour un mouvement populaire (UMP, Union for a popular movement) in opposition to his agenda. Valls will introduce the 2015 budget in the autumn, and if he fails to pass it later this year, his government could fall and Hollande might be forced to call snap elections that the Socialists would almost certainly lose. Continue reading Valls-Montebourg fissure could bring early French elections