Nearly 7,000 people have died in the Philippines since controversial president Rodrigo Duterte launched his ‘drug war’ last July, following his insurgent populist victory.![]()

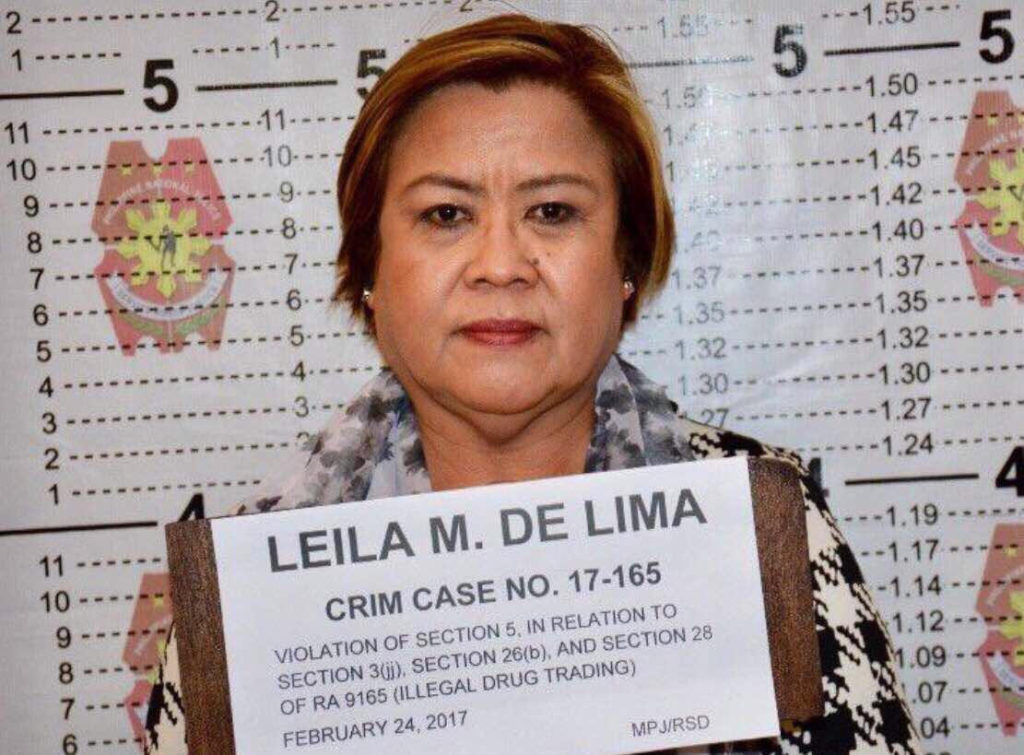

Last week, the chief domestic critic of Duterte’s human rights record, senator Leila de Lima, was imprisoned on charges of drug-related corruption — charges that have been widely met with disgust from human rights groups who say that her arrest is politically motivated.

Since taking power, Duterte has bragged about killing drug dealers himself when he served as mayor of of Davao City, all while encouraging police (and others) to engage in extrajudicial killings of suspected drug dealers. Last September, Duterte threatened to kill up to 3 million drug addicts, likening himself to Adolf Hitler.

As human rights watchdogs across the world continue to sound alarms, Duterte’s encouragement is already showing signs of spiraling out of control, with far more suspected criminals killed at the hands of vigilante groups than the official police. A South Korean businessman was strangled to death in policy custody, forcing even the sharp-tongued Duterte to pause for a moment. Nevertheless, Duterte has pledged to continue his aggressive campaign through the end of his six-year presidential term in 2022. His blunt speaking, often in vulgar terms, has brought him popularity with an electorate that elected him to be tough on crime and on drug use. Even as Duterte risks becoming an international pariah over human rights, Philippines still give him an 83% approval rating as of the beginning of 2017.

De Lima, who previously served as the chair of the Philippine Commission on Human Rights under former president Gloria Macagapal-Arroyo and as the country’s justice secretary under Benigno (‘NoyNoy’) Aquino III from 2010 to 2015, has called Duterte a ‘murderer’ and a ‘sociopathic serial killer.’ De Lima has led the fight against Duterte’s drug war from the Senate, the 24-member upper house of the Philippine Congress. Last September, Duterte’s allies removed her from the Senate’s Justice and Human Rights Committee, where she hoped to investigate the abuses of the drug war, most notably the extrajudicial killings.

The two politicians have a difficult history. In 2009, when she was still heading the human rights commission, De Lima first investigated rumors of ‘death squads’ in Davao City, where Duterte served as mayor for over two decades, for the first time in 1988, prior to his election to the presidency last May.

Upon surrendering to authorities Friday morning, De Lima embraced her new, jarring role as one of the world’s most prominent political prisoners: Continue reading De Lima’s arrest represents sharp turn against Philippine rule of law