Two small African neighboring countries. Both are densely populated with between 10 and 12 million people. Both have emerged from Tutsi-Hutu civil wars in the past two decades. ![]()

![]()

Burundi’s president Pierre Nkurunziza seems headed for a difficult and bloody reelection against the will of a large segment of the Burundian people and arguably in violation of the constitution’s prohibition on serving more than two consecutive terms. Though Nkurunziza unconvincingly argues he is running for his second term under the current constitution, the Arusha Accords that ended Burundi’s civil war made it clear that Nkurunziza should get up to a decade in power — not 15 years (or, potentially, more).

Nkurunziza’s push for a third term resulted in a brutal crackdown over the past 18 months amid growing political violence, twice necessitating the delay of an election originally scheduled for June. When election results, the first of which are scheduled to be announced later Friday, show that Nkurunziza easily won reelection, many Burundians will refuse to recognize the victory, and there’s a chance that Burundi could collapse into greater violence — or even civil war.

* * * * *

RELATED: Rwandan election highlights tension between ethnic, economic stability and authoritarianism

RELATED: Nkurunziza’s reelection effort brings violence in Burundi

* * * * *

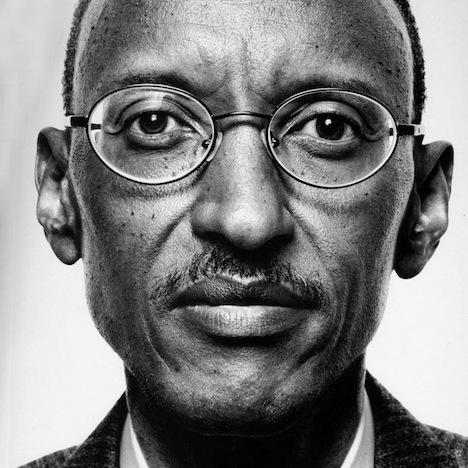

Next door in Rwanda, however, president Paul Kagame seems preparing for reelection in 2017, notwithstanding constitutional term limits. Unlike Nkurunziza, if Kagame (pictured above) does find a way to seek another term, he will largely do so to the widespread acclaim and genuine approval of the Rwandan people — and with the assent of Rwanda’s Chamber of Deputies, which passed a law earlier this week that will allow Kagame to run for a third term in his own right, in response to a petition signed by 3.7 million Rwandans.

While Nkurunziza has suffered international condemnation for pushing forward with reelection, Kagame will almost certainly receive far less scrutiny if, as expected, he runs for another term in 2017.

Kagame isn’t immune to political repression — the ruling Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) controls an effectively one-party country where opposition leaders or journalists are harassed or imprisoned, sometimes to the point of exile.

So what’s with the double standard? Continue reading Why Kagame’s reelection in Rwanda will be different than Nkurunziza’s