For decades, presidential politics in parliamentary democracies were boring affairs — if popular elections were even held for the position, they typically featured technocrats or independents. Politicians, if they ran for what are mostly ceremonial presidencies, would be episodes that ended a successful political career. ![]()

That’s still generally the case in western Europe — presidents like former Labour firebrand Michael D. Higgins in Ireland, one-time foreign minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier in Germany, and the charismatic communist Giorgio Napolitano in Italy all ended (or are ending) their political careers as figureheads.

But increasingly, in emerging democracies in eastern Europe, it’s becoming a power play for popular prime ministers to wage campaigns for a previously ceremonial presidency, using the ‘mandate’ of popular election as a bid to suffuse the presidency with far more than ceremonial power.

It is a gambit that’s worked in the Czech Republic and in Turkey, where presidents Miloš Zeman (since 2013) and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (since 2014) have succeeded, to some degree, in shifting some power from the parliamentary branch of government to the presidential. The Czech Republic remains a parliamentary democracy, but Zeman, who is running for reelection in 2018, shrewdly took advantage of the country’s first direct presidential elections to carve a new role for the Czech presidency in domestic and foreign policymaking. Erdoğan not only won the Turkish presidency, but hopes to formalize constitutional changes to enshrine presidential power in a high-stakes April 16 referendum.

It failed in Slovakia, where sitting prime minister Robert Fico lost the 2014 presidential election to independent businessman and philanthropist Andrej Kiska. So it’s a power move that can sometimes backfire — Fico managed to remain Slovakian prime minister, but his center-left party dropped from 83 seats to 49 in the National Assembly in last March’s parliamentary elections after a swing of 16% away from Fico’s party.

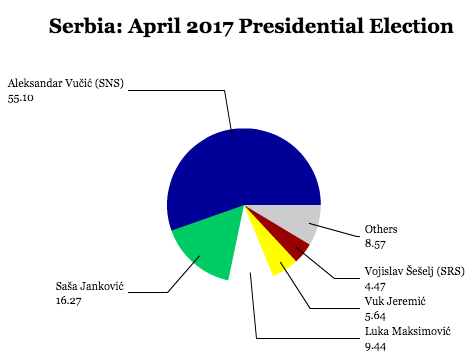

There will be no such regrets for prime minister Aleksandar Vučić, who easily won a first-round victory with 55% of the vote among an 11-candidate field, cementing control of the Serbian government not only in the hands of the ruling Serbian Progressive Party (Српска напредна странка / SNS), but, in particular, under the personal command of Vučić, who nudged incumbent Tomislav Nikolić to stand aside from a reelection bid in late February.

It will make Vučić even more powerful than Boris Tadić, a center-left and pro-EU leader who similarly dominated Serbian politics as president from 2004 to 2012. Though Nikolić narrowly defeated Tadić five years ago in a runoff, Vučić (and not Nikolić) held more sway over Serbian government over the last half-decade, increasing his grip on power over a series of three parliamentary elections between 2012 and 2016. Vučić’s presidential victory means that power is now likely to swing (once again) to the Novi Dvor, the Serbian presidential palace.

Over the next two months, as he prepares to take the presidential oath on May 31, Vučić, who remains prime minister for the time being, is likely to choose one of several cabinet members as his successor — leading names include two independents appointed by Vučić to his cabinet, finance minister Dušan Vujović or public administration minister Ana Brnabić (who would not only be Serbia’s first female prime minister, but its first openly lesbian one, too). Nikolić, over the weekend, hinted that he would retire from party politics altogether, which would seem to eliminate him as prime minister. Former justice minister Nikola Selaković, a rising star within the SNS, is also often mentioned.

After nearly a decade of pro-European rule under Tadić and his allies, the Progressives slowly started consolidating power after winning the most seats (73) in the May 2012 parliamentary election. The SNS immediately joined a coalition with the smaller Socialist Party of Serbia (Социјалистичка партија Србије / SPS), which had also gained many seats in the same election. To win the Socialists’ support, the SNS permitted its leader, Ivica Dačić, to serve as prime minister, with Vučić serving as his deputy prime minister. In the same election, Nikolić narrowly won the Serbian presidency.

Two years later, the Progressives were so confident in their position that they triggered snap elections in March 2014, a decision that rewarded the party with a staggering landslide, giving it 158 seats in the 250-member National Assembly. This time, it was Vučić who became prime minister, with Dačić taking a demotion to deputy prime minister and foreign minister.

Vučić once again called snap elections in April 2016 and the SNS once again dominated the polls, retaining 131 seats in the National Assembly (with their Progressive coalition partners winning another 29) on a mandate for ‘stability.’

Notably, the once-dominant pro-European and center-left Democratic Party (Демократска странка / DS) fell to just 16 seats after Tadić left the DS in 2014, upon losing the leadership, to form a new party. The Democrats fell behind even the far-right Serbian Radical Party (Српска радикална странка / SRS), a nationalist group that returned to parliament for the first time since 2012, after Nikolić and many of the party’s more moderate members left in 2008 to form what is today the Progressive Party. To an even greater degree than in 2012 and 2014, the 2016 elections left the mainstream opposition to the Progressive-led coalition divided and weaker than ever.

Saša Janković, an independent candidate who from 2007 until earlier this year served as the country’s ombudsman, an authority created in 2005 to protect citizens’ rights and freedoms, finished far behind in second place, though he valiantly called it a ‘beginning’ for a new opposition in Serbia. That remains to be seen.

But its 25-year-old comedian Luka Maksimović, the parody candidate of a satirical political movement, ‘Hit it Hard,’ mocking Serbia’s political elites and running in character under the pseudonym of ‘Ljubiša Preletačević’ or simply by his nickname, ‘Beli,’ (the ‘White One,’ a nod to the candidate’s white suit) who making the most waves. Beli finished in third place with nearly 10% of the vote after dominating the presidential campaign on social media:

[Beli] comes complete with fake university diploma, wealth that is unaccounted for and a tendency to make empty populist promises to win votes. And all that while wearing his trademark all-white suit.

Last year, after the local elections in April, the spoof political group unexpectedly came second in Mladenovac, one of 17 municipalities in the Belgrade City Assembly. The suprise showing launched Beli as an instant celebrity.

It wasn’t the most robust field — Vucic’s level of support was larger than any president’s since Vojislav Koštunica (57.7%) in December 2002, also the last validated election not to advance to a runoff.

Serbia officially became a candidate for EU membership in March 2012, shortly before the Progressives returned to power in that year’s parliamentary election, though Nikolić (once closer to Russian than to European leaders) and Progressive leaders have so far embraced EU membership as a goal. Negotiations opened in early 2014 and are ongoing, though Serbia has only opened eight of 35 chapters for EU accession. By and large, the carrot of EU accession has so far calmed tensions between Serbia and Kosovo, though Belgrade continues to refuse to recognize Kosovar sovereignty.

In line with longtime cultural and political ties with Russia, however, Serbia’s government has also reached out to Moscow in ways that the earlier Democratic Party government did not. For example, Belgrade today doesn’t support ongoing EU sanctions against Russian president Vladimir Putin’s government, and Vučić last week — just days before the election — traveled to Moscow for a high-profile meeting with Putin to demonstrate the close relations between Russia and Serbia.

Despite the outreach to Moscow, Vučić has doubled down on Serbian efforts to comply with the standards necessary to bring the country into the European Union, even at a time when anti-EU sentiment is on the rise. Vučić is wagering that Serbia can prove itself a vital link, economically and geopolitically, between the European Union and Russia — a relationship at a post-Cold War nadir. Though EU accession has dropped in popularity among the Serbian electorate, Vučić remains committed to his project of bringing ‘stability’ to Serbia, which includes keeping the country on the path toward accession. Two weeks before he met with Putin, Vučić also met with German chancellor Angela Merkel, sending a message of reassurance about Serbia’s commitment to the European Union as well as the rest of the western Balkan countries that also hope to achieve EU membership.

Critics argue that Vučić, who served as information minister to the late and controversial president Slobodan Milošević, has undermined the judiciary and the media within Serbia. They fear that as the European Union turns inward, with the ongoing challenges of negotiating the United Kingdom’s EU exit and with an increasingly unreliable American ally in the Trump administration, EU officials will be more lenient to Serbia as a key conduit to the Balkans and, indeed, to Russia. Protestors gathered Monday across Belgrade and other major cities denouncing the rise of a Vučić-led dictatorship, but Vučić on Monday was already off to a meeting of Balkan leaders in Sarajevo, including the sitting Croat member of the Bosnia-Herzegovina tripartite presidency and other leading officials.

Far behind in fourth and fifth place were Vuk Jeremić, now an independent (formerly of the Democratic Party) and a former foreign minister, and Vojislav Šešelj, the controversial ultranationalist leader of the Serbian Radical Party who spent 11 years in detention and on trial for his role in war crimes.