It’s not just the United States and western Europe facing down the threat of xenophobia.![]()

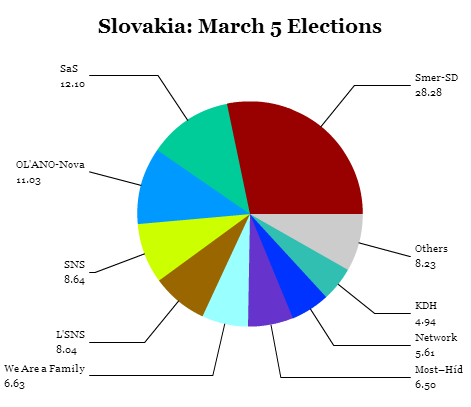

Slovakia’s voters on Saturday delivered a victory to prime minister Robert Fico and the center-left Smer–sociálna demokracia, (Direction/Social Democracy), which has governed Slovakia since a landslide win in 2012.

But Fico, who lost a 2014 presidential bid to businessman Andrej Kiska, saw his majority eliminated, and Smer-SD will hold just 49 of the 150 seats in the Národná rada (National Council).

Meanwhile, an openly ultranationalist, far-right party, Ľudová strana – Naše Slovensko (L’SNS, People’s Party/Our Slovakia), accurately described as a neo-Nazi party, won 8% of the vote and 14 seats in the new parliament after waging a campaign attacking not only the waves of African and Middle Eastern migrants arriving in Europe, but NATO, the European Union, the European security alliance with the United States and same-sex unions.

Marian Kotleba, who won a shock victory in regional elections in 2013 in Banska Bystrica in the center of the country, often wears a uniform modeled after the Nazi-backed puppet state that governed Slovakia during World War II. Despite the party’s radical politics, Kotleba emphasized economic opportunity and corruption, corralling the same kind of ‘anti-establishment’ sentiment that’s gripped much of Europe and the United States.

The L’SNS is not to be confused with the Slovenská národná strana (SNS, Slovak National Party), which also embraces a hardline nationalist stand on immigration. The SNS will return to the National Council after a four-year absence, when it most recently aligned itself with Smer-SD as a partner in Fico’s first government from 2006 to 2010.

Politically, that will not be difficult for Fico, a center-left populist who has enacted progressive economic policies in Slovakia (which enjoyed GDP growth of 3.6% in 2015) but who is increasingly opposed to Syrian and other migrants in Slovakia, aligning himself with hardline right-wing figures like Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán. Fico earlier this year bragged about monitoring every single Muslim in Slovakia. Though few refugees view Slovakia as a top destination, Fico has argued that an influx of even a handful of Muslims could endanger Slovaks.

Kiska, who now holds the presidency, has argued that because Slovakia draws so few refugees, Fico’s harsh anti-Muslim rhetoric is unwelcoming and unkind. In light of the disappointing result for Smer-SD, Fico may have wished that he focused on the fruits of his government’s economic policies instead.

The SNS, which now holds 15 seats, would not bring Smer-SD a ruling majority, however, so Fico may have to broaden his appeal to one of five parties that lie within Slovakia’s deeply fractured center-right.

Fico’s largest rival will be Sloboda a Solidarita (SaS, Freedom and Solidarity), an economically liberal party. With 21 seats in the new parliament, it benefited from the collapse of the more traditionally center-right Kresťanskodemokratické hnutie (KDH, Christian Democratic Movement), which lost all 16 of its seats after falling below the 5% proportional representation threshold. But its leader, Richard Sulík, a former National Council speaker and member of the European Parliament, has ruled out any coalition with Fico.

As far as that goes, so have the other four center-right parties that all won between 10 and 19 seats in Saturday’s election, though a coalition among all five would only net 72 seats, just shy of a majority.

The election leaves the shape of Slovakia’s next government very much in doubt, joining Spain and Ireland, which are both engaged in coalition talks after elections that left their own respective parliaments sharply divided among multiple parties. With Slovakia set to take the reins of the rotating, six-month European Union presidency in July, Kiska may push instead for a unity, caretaker government to get Slovakia through the end of 2016. If he succeeds, it may not be his presidential rival, Fico, who leads that coalition.