As global politics takes its strongest lunge towards ultranationalist populism in the postwar era, Croatian voters on Sunday delivered a fresh (if narrow) mandate to a conservative party now headed by a moderate and technocratic former diplomat.![]()

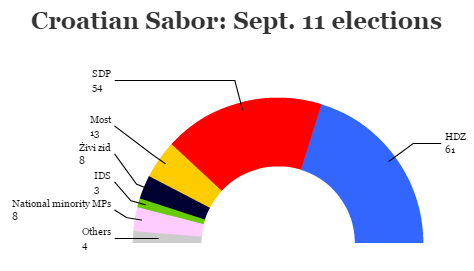

In a repeat of last November’s elections, the conservative Hrvatska demokratska zajednica (HDZ, Croatian Democratic Union) placed first but short of the absolute majority that it needed to govern alone.

Just as after last year’s elections, it will now look to form a coalition with Most nezavisnih lista (Bridge of Independent Lists), a reformist and centrist party formed in 2012 that fared slightly more poorly in the September 11 parliamentary election than last year. Nevertheless, Most continues to hold the margin of power for the next Croatian government, and it’s very likely to join an HDZ-led coalition. Together, the HDZ and Most are just two seats short of a majority, which they might pick up from independents MPs.

Andrej Plenković, a mild-mannered diplomat, is the HDZ’s fresh-faced leader, and he’s part of a rising generation of Croatians who came of age, politically speaking, long after Yugoslavia’s breakup. Though he leads the Croatian right in what has become an increasingly nationalist moment, Plenković’s career is rooted in foreign policy and diplomacy, not populist politics. A longtime member of the bureaucracy in Croatia’s ministry of foreign and European affairs, Plenković served for five years as deputy ambassador to France, then as secretary of state for European integration from 2010 to 2011, shortly before Croatia acceded to the European Union. Since 2013, he has also served as a member of the European Parliament (after a brief two-year stint in the Croatian national parliament).

* * * * *

RELATED: Reform-minded Most party set to play kingmaker in Croatia

* * * * *

Yet as the aftermath of the 2015 election showed, coalition agreements are easier conceived than executed. After 76 days of negotiations, the HDZ and Most agreed in January 2016 to form a coalition headed by a non-partisan prime minister, Tihomir Orešković, a dual Canadian national and pharmaceutical businessman. Tasked with a nearly impossible project to boost GDP growth and cut Croatia’s debt, the government seemed to be on track to meet its goals.

Nevertheless, the government lasted just five months.

The HDZ’s leader at the time, Tomislav Karamarko, and deputy first prime minister under Orešković, was implicated in a conflict-of-interest scandal over his wife’s interest in Hungary’s state oil company. The long saga ended with increasingly difficult relations between Karamarko and Most‘s leader, Božo Petrov. Karamarko refused initially to resign, angering Petrov. Eventually, the crisis led to a vote of no confidence in the Orešković government, with the support of both the HDZ and the center-left Socijaldemokratska partija Hrvatske (SDP, Social Democratic Party of Croatia).

That set the stage for the snap elections on September 11, and the SDP obviously hoped that the scandal would restore it to power. But with Karamarko out as HDZ leader, that didn’t happen, and the SDP’s leader since 2007, Zoran Milanović, who served as prime minister from 2011 to 2016, stepped down in the aftermath of the SDP’s disappointing showing. It didn’t help that he was caught in a secret recording disparaging Bosnian and Serbian leaders.

This time around, Plenković is making it clear that he wants no ‘political experiments,’ — i.e., any coalition will feature Plenković, and not a technocratic outsider, as prime minister. As much of the conflict between the HDZ and Most involved Karamarko, however, Plenković could credibly forge a much more stable government.

Turnout fell drastically from just 10 months ago — from 60.82% last November to just 52.59% last weekend, perhaps a warning to politicians in Spain considering its third election within the same 12-month period.

But more alarming is the significant rise in hard-right nationalism in Croatia, just as throughout other parts of Europe. Zlatko Hasanbegović, the former HDZ culture minister in Orešković’s short-lived government, has made some particularly troubling comments praising Ustaše, an interwar fascist organization in Croatia responsible for the murder of thousands of minorities, including Roma, Jews and Serbs, in the 1930s and early 1940s. Increasingly, the Croatian right is embracing some of the symbols and chants of Ustaše. Karamarko and his allies, who tried to move the HDZ more to the right, in part enabled much of the recent turn to Croatian nationalism. That, along with Milanović’s disparaging comments, has complicated Zagreb’s relations with Balkan neighbors like Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina.

It seems unlikely that Hasanbegović will be a member of the next Croatian government.

Notably, Živi zid (Human Shield / Living Wall), a populist, outsider, anti-trade and eurosceptic group won eight seats, entering the Sabor, the Croatian unicameral parliament for the first time. Though it’s more leftist, and it’s not particularly interested in lionizing Ustaše, it indicates the growing disenchantment of Croatian voters with the two mainstream parties.

All of which is reason to encourage Plenković’s success.

He hopes to emulate the centrist, cooperative approach of German chancellor Angela Merkel. That appears to have helped him, as party leader for just four weeks and a little-known figure within his own country, to win over skeptical voters. But he also benefits from credibly representing a clean break from Karamarko and former disgraced HDZ prime minister Ivo Sanader, the latter convicted in 2011 on corruption charges.

Though Plenković hopes to boost an economy that continues to recuperate from recession and joblessness, he also plans to introduce tax reform and build on the fiscal accomplishments of the prior government. If he succeeds, even moderately, it could give him credibility to tamp down the most hard-right elements within the HDZ, thereby smoothing relations at a time when Balkan cooperation is crucial on refugee policy and ongoing EU accession talks for Croatia’s neighbors.

While Croatia’s unemployment is at an eight-year low, it’s still hovering at just above 13%, and while the economy is now expected to grow by slightly more than 2% this year, public debt has now crept up to just over 85% of GDP, binding the next government to take a more conservative approach to spending.