Voting under the penumbra of an ongoing political crisis in the United Kingdom following last Thursday’s referendum, in which a bare majority of British voters chose to leave the European Union, Spanish voters in Sunday’s general election — the second in seven months — fell back on established parties instead of more radical newcomers.![]()

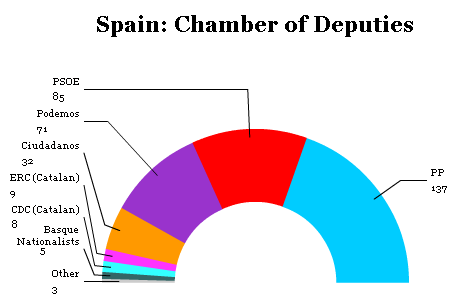

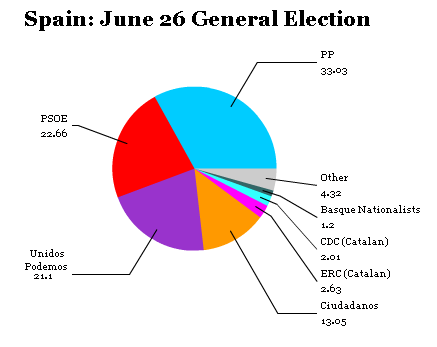

Despite polls (and even exit polls) that predicted the rise of Unidos Podemos, a joint ticket of Spain’s far-left communists and Podemos, the newer anti-austerity movement, the ticket won the same number of seats in the lower house of Spain’s parliament, the 350-member Congreso de los Diputados (Congress of Deputies), than it had after the December general election.

Forecasts that Unidos Podemos would overtake the center-left Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE, Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party) proved wrong. The PSOE, under the leadership of Pedro Sánchez, remains the largest leftist force in Spanish politics.

Unfortunately for Sánchez, the PSOE fell further behind the governing center-right Partido Popular (PP, the People’s Party) of prime minister Mariano Rajoy, which won 137 seats — a 14-seat increase since the December 2015 elections. Those gains came mostly as a result of record-low turnout and a subtle migration back to Rajoy’s party from the upstart, liberal Ciudadanos, which lost eight seats in last Sunday’s voting.

So what next? In an election where voters largely returned the same verdict, Spain’s political class is now looking at another round of coalition talks as a country with a traditional two-party system now copes with four major parties.

At the heart of these talks, however, is the PSOE, which is now positioned as the leading swing vote between Spain’s conservatives and Spain’s hard left. No matter what comes next for Spain, the PSOE will almost certainly determine the outcome.

So as Spain’s political leaders get down to the business of coalition talks in the days and weeks to come, the most important factor to keep in mind are the PSOE’s political incentives (and, to a lesser degree, Sánchez’s incentive to remain PSOE leader in the hopes of winning a future election).

Roughly speaking, there are still three options available to Spain, just like after the last election:

- a German-style ‘grand coalition’ between the PP and the PSOE (or a more informal arrangement whereby the PSOE allows a PP-led minority government to rule),

- a Portuguese-style ‘coalition of the left’ that incorporates the PSOE, Unidos Podemos and possibly Ciudadanos, or

- a failure of coalition talks and a third set of elections, as happened in Greece in the summer of 2012.

Though the PSOE ultimately outpolled Unidos Podemos, it spent most of the leadup to the June elections terrified that Unidos Podemos would usurp its role as the traditional party of the Spanish left. This is the party’s worst nightmare, because it is exactly what happened in Greece — PASOK, for decades the leading party of the Greek left, was increasingly marginalized by the more radical SYRIZA’s rise between 2012 and 2015.

* * * * *

RELATED: Spain heads toward fresh elections on June 26

* * * * *

For the PSOE to join hands with Rajoy (or another conservative prime minister) in a grand coalition, tasked with continued budget cuts and tax increases at a time of sustained unemployment rates of over 20% (and even worse for young Spaniards), would be political suicide. It would make Pablo Iglesias the opposition leader and it would make Unidos Podemos the clear choice for anti-austerity and left-wing voters of all stripes. Indeed, the PSOE has already ruled this out, despite Rajoy’s hopes to form a grand coalition.

The PSOE could still hope to lead a multi-party government, but talks among Sánchez, Iglesias and Albert Rivera, the Ciudadanos leader, failed miserably between December 2015 and May 2016. Together, the three parties have even fewer seats today than they did before the June elections. There’s no reason to believe that they can find common ground of much of anything, including economic policy. But, most importantly, Rivera and Sánchez are unwilling to give Catalans a free vote on independence. In contrast, that is one of the key promises that Iglesias and Podemos have made — and it’s one reason why the far left has done so well in Catalonia and the Basque Country in national elections. The party’s other leaders, like Andalusian regional president Susana Díaz and beloved former prime minister Felipe González have ruled this out as well, essentially tying Sánchez’s hands.

But if the PSOE, as the crucial swing vote, fails to find common ground for a coalition and Spanish voters go to the polls for a third consecutive time, there’s no guarantee that the PSOE will come out on top over Unidos Podemos yet again. The PSOE only won around 1.5% more support on Sunday, just three days after the Brexit referendum spooked Spanish markets (and perhaps voters). The PSOE’s surprise strength will give Sánchez some room to maneuver; nevertheless, the PSOE has notched historically low support under his leadership. In particular, Díaz might decide to challenge Sánchez for the leadership, though even in her own Andalusia, the PP managed to win more votes than the PSOE.

So what’s left? None of these options seem incredibly great for the PSOE.

Together with Ciudadanos, the PP could cobble together 169 seats, just shy of an absolute majority. The People’s Party is clearly the winner of the July elections — it made the greatest gains and it extended its lead to become, by far, the party with the most support in the Chamber of Deputies. So there’s a small-d democratic case that it should have the chance to lead a government. That doesn’t mean that Rivera or other potential coalition partners will necessarily accept Rajoy himself as prime minister or countenance the number of troubling corruption and abuse of power scandals that have emerged out of Rajoy’s first five-year term — most recently, that interior minister Jorge Fernández Díaz used government inquiries to try to smear Catalan nationalists.

Given that a joint PP-Ciudadanos coalition would be so close to a majority, the most rational response for the PSOE is to allow a conservative minority government for the foreseeable future. Unlike a formal grand coalition, it gives Sánchez the requisite distance he’ll need from Rajoy to wage a credible future campaign against the Spanish right. It also avoids lengthy and difficult (and largely fruitless) negotiations with Unidos Podemos and, on its face, respects that voters clearly chose the PP over the PSOE.

Finally, Sánchez (and the rest of Spain) would be able to take a break from perpetual campaign mode, and it would give the PSOE the strategic power to decide when and how the next election will be held. If a center-right coalition government goes too far, the PSOE can force a vote of no confidence and send Spain back to the polls.