Turkey is not going to become a member-state of the European Union anytime soon.![]()

![]()

No matter what joint talks take place next week, next month or next decade between Turkish and European diplomats, it is absolutely incomprehensible that the European Union, with or without the United Kingdom, would be willing to grant membership to a state with the level of economic corruption and political authoritarianism as Turkey. Full stop.

Even if European diplomats did, though, and even if each of the other 27 member-states of the European Union wanted to admit Turkey — which today borders war-torn Syria and destabilized Iraq — all it would take is for a British prime minister to say, simply, ‘No.’

That’s because EU membership is one of a handful of issues accomplished only by unanimity of the European Union’s member-states. For example, Greece has held up Macedonia’s EU accession hopes for years over a long-simmering conflict over the name ‘Macedonia,’ and the Greeks, for the better part of the last century, have been none too keen on doing many favors for their Turkish rivals, either.

Last week, EU officials cheekily informed Turkey that the country has not yet met all of the EU conditions for visa-free travel to the European Union, one of the rewards that Turkey received as part of a controversial deal to stem the flow of Syrian and Iraqi migrants from Turkey into the European Union. Though critics of German chancellor Angela Merkel argue that she sold out EU values in exchange for a Turkish solution to the EU migration crisis, Europeans are holding firm in requiring that Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan stop using ‘anti-terror’ laws to arrest journalists, academics and political opponents. This is hardly the stuff of happy Turkish-EU relations.

That hasn’t stopped prominent leaders in the ‘Leave’ campaign — including former London mayor Boris Johnson — from arguing that, in essence, a vote in today’s referendum to leave the European Union is the last chance that British voters have to end Turkey’s inevitable EU accession and, with it, an implied deluge of hundreds of thousands of Turkish migrants into the United Kingdom as a result of the free movement of EU workers throughout the single market. Johnson, for what it’s worth, actually once supported Turkey’s EU accession — of course, it was long ago when Erdoğan was a genuinely democratic prime minister and not as an autocratic president.

Still, it’s an ugly aspect of a debate that’s rapidly turned poisonous as the main topic of concern has shifted from the economic consequences of Brexit to the more contentious topic of immigration.

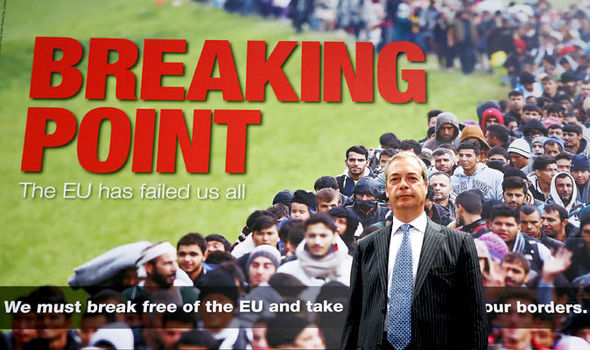

Nigel Farage, the leader of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), just hours before Labour MP Jo Cox’s assassination last week, unveiled a poster that put the ‘Leave’ case explicitly and directly in terms of keeping immigrants out of Britain. ‘BREAKING POINT,’ screamed the bright red, capital letters, superimposed on a photo showing a virtual human river of mostly non-EU migrants in Croatia last year.

Farage has had no qualms about the caustic poster, though Johnson and other Tory leaders, like justice secretary Michael Gove, have disavowed the UKIP approach as crude and xenophobic. Earlier this week, former Conservative party chair Sayeeda Warsi jumped from the ‘Leave’ to the ‘Remain’ campaign, denouncing the ‘hateful xenophobia’ of the Farage-style tactics.

But the poster represents just the latest in a slippery slope of arguments from Farage, Johnson and Gove that all boil down to this: the only way to control immigration is for the United Kingdom to leave the European Union on June 23. Johnson, in no uncertain terms, has said that it is impossible for British officials to control immigration while remaining a member of the European Union and that rising migration has strained the National Health Service and other public services, while suppressing British wages by increasing the supply of labor.

Immigration is a real issue for voters (both Conservative and Labour) in the United Kingdom, and it’s worth taking seriously voter concerns about the economic, social and cultural effects of immigration, especially after the most intense wave of migrants to the European continent in decades. One of the greatest credibility problems of the Remain campaign has been that, Conservative prime minister David Cameron has been unable to meet a pledge to reduce net migration to below 100,000. Instead, net migration in 2015 reached 333,000, a near-historic record, though Cameron argues that it’s because of the unnatural strength of the current British economy. Jeremy Corbyn, elected last summer as the leader of the center-left Labour Party, argues that there can be no upper limit to immigration, in light of the principle of free movement of workers within the single market.

But the ‘Leave’ campaign is being somewhat dodgy by conflating two very different sets of migrants. The first set includes those non-British workers from within the European Union that, pursuant to the rules of the single market, have come to work in the United Kingdom.Of the 333,000 net migration into the United Kingdom in 2015, only 184,000 of these were from inside the European Union.

The second set includes immigrants from outside the European Union, and that’s a group that contains everyone from skilled technicians from, say, the United States or India, to refugees and other asylum-seekers from places like Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq and Eritrea. Even if the British chose magically to leave the European Union on the first day of 2015, shutting its borders entirely to EU immigrants, it would still have faced a deluge of 188,000 additional non-EU immigrants. It perhaps would have faced an even higher number without French and EU assistance holding back would-be migrants trying to cross the English Channel at Calais. It’s hard to imagine the same level of cooperation from EU officials in a world where the United Kingdom is, in fact, no longer part of the European Union.

What’s more, if the United Kingdom leaves the European Union but still hopes to access the single market — the integrated free-trade zone that spans the European Union, Norway, Iceland, Switzerland and elsewhere — it will almost certainly have to agree to some level of free movement, possibly even without the kind of ‘benefit brake’ that Cameron negotiated with EU leaders in the lead-up to the in-out referendum today.

Of course, it is also true that because the United Kingdom (like Ireland) is not a member of the Schengen zone, it already controls its own borders to a greater degree than much of the rest of Europe (including Norway and Switzerland, both of which are Schengen members!)

So Brexit is not a magic bullet that would restore control to British lawmakers over immigration and, in some key ways, it might even make it more difficult for the British to control future waves of migration. But you wouldn’t know it from the tone of the debate. Though Remain’s proponents would have done well to engage more openly and honestly about the effects of immigration on weary voters, the Leave campaign’s mistruths have clouded a complex tactic by embracing the kind of xenophobia in which Farage routinely traffics.

It’s also the kind of argument that will mar any Leave victory with unrealistic expectations about what Brexit could ultimately accomplish, when it becomes clear that the European Union wasn’t the only factor in such a multi-faceted phenomenon as global human migration.