Fifty-four years after Amma Magnani starred in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s classic Mamma Roma, redefining feminism for Romans and Italians alike, the Eternal City is getting what centuries of imperial and papal rule never allowed — a woman in charge.![]()

![]()

Say what you will about her, unlike Magnani and unlike the founder of her party, Beppe Grillo, Virginia Raggi is no comedian.

For a movement that has sometimes suffered by the fact that its most prominent leader and founder is Grillo, a comic-turned-politician, it now enters a phase where it will be judged by governance, and not just politics. The protest Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S, the Five Star Movement) emerged in Italian politics in the 2013 parliamentary elections as an anti-austerity and anti-eurozone force, drawing votes from the remnants of Silvio Berlusconi’s center-right coalition as well as disenchanted leftist voters.

The Five Star Movement controls 91 seats in the 630-member lower house of Italy’s parliament, the Camera dei Deputati (Chamber of Deputies), where its role has chiefly been to throw sand at both the Italian right and the dominant Partito Democratico (PD, Democratic Party) of prime minister Matteo Renzi.

That will all change after Sunday, when Rome’s (and Turin’s) voters elected two women affiliated with the Five Star Movement, giving it the opportunity to mature into a new role — a functional party of municipal government.

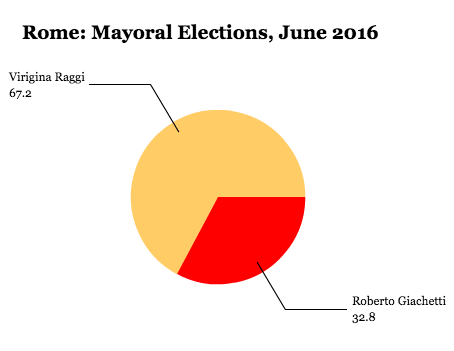

The 32-year-old Chiara Appendino has won a runoff to become the next mayor of the northern industrial city of Turin, but the real prize is Rome, where Virginia Raggi has easily won a runoff against Democratic Party challenger Roberto Giachetti to become the Italian capital’s first female mayor. It is also, by far, the most high-profile electoral success of the Five Star Movement to date.

Rome, home to nearly 2.9 million people, is the European Union’s fourth-largest city after London, Berlin and Madrid. But successive governments have left voters angry, just about everything — roads are worn, public transportation chugs along slowly and trash often goes uncollected. Residents have been dreaming for decades of a third line for the city’s burdened two-line subway system, but construction has stalled under each of the last two administrations.

The last elected mayor, Ignazio Marino, a novice in Italian politics and a former transplant surgeon, resigned in disgrace late last year after just two years in office, implicated in an expense scandal in which Marino apparently charged around €20,000 for personal dinners with friends.

Marino’s personal scandal followed the even wider Mafia Capitale scandal, which saw politicians misappropriate public funds (including funding set aside for the education of marginalized Roma children) to organized crime units in both Rome and the surrounding Lazio region. Moreover, by the time Marino finally resigned, no one — not even Renzi, let alone everyday Romans — seemed to have much faith in Marino’s ability to run the city. The Genoa-born Marino came to politics only in 2006 with his election to Italy’s Senato (Senate).

Marino managed to win election in June 2013 only because of the massive unpopularity of his predecessor, Gianni Alemanno, a controversial figure and Berlusconi ally with former ties to the neofascist right who seemed more concerned with stirring up his national profile than the mundane matters of day-to-day governance in Rome.

Raggi is, like Grillo, a relative neophyte in Roman (and Italian) politics. But the 37-year-old attorney and, for the past three years, a Roman city councillor, has run the kind of campaign that has convinced Roman voters she can credibly run the city, while also representing the kind of change that they first sought in Alemanno and, later, in Marino. Unlike Marino, who left the office vacant when he resigned last October, Raggi was born and raised in Rome.

That means that voters have either agreed with or ignored her routine dismissal of Rome’s bid for the 2024 Olympics (and, to be fair, if you’ve ever spent any significant time in Rome, you too might wonder how the city might, at low cost, build the kind of temporary infrastructure for a modern, 21st century Olympics). At one point, Raggi even suggested that low-income voters return to the barter system, as if Rome were some stagnant fossil of a postwar Rossellini film. Those missteps have been far and few between, however, for a candidate who has demanded accountability in everything from trash collection to tallying the precise amount of Rome’s staggering debt load. She also wants to restart Rome’s bike-share program, take away the city council’s credit cards and attempt to pull Rome from the perpetual brink of bankruptcy.

Many commentators across Italy have been describing the results (in Turin as well as Rome) since the first round on June 6 as a setback for Renzi. But Raggi’s success might perhaps be better for the reformist, 41-year-old prime minister than another victory for his party, if it means that Rome will avoid suffering under another unpopular and incapable mayor. While it’s true that Renzi has staked his premiership on an upcoming October referendum over constitutional reforms (and, indeed, the promise of further reforms to Italy’s economy and public sector), even a week is a long time in politics. October will take care of itself in its own context.

It’s not surprising that Roman voters, after the grandstanding, neofascist failures of the Alemanno administration and the ethical (and more mundane) failures of the Marino administration, would turn to Raggi. Though Raggi has made plenty of mistakes throughout the campaign, Renzi himself might find much to like in Rome’s new mayor-elect, who appears, at first glance, to be a far more responsible official than either Alemanno or Marino.

If any country has proven difficult to pivot away from corruption, tradition and resistance to reform, it’s Italy. But especially Rome, which, for all its classical pedigree, might also fit John Kennedy’s notable summary judgement of Washington, D.C. — northern charm and southern efficiency. No other city in Italy manages quite to harness the pathologies of Italy’s cultural and economically divided north and south as much as Rome.

Raggi, like many charismatic and inspirational figures of change, risks running the disappointment that she will fail in reforming Rome’s political culture.

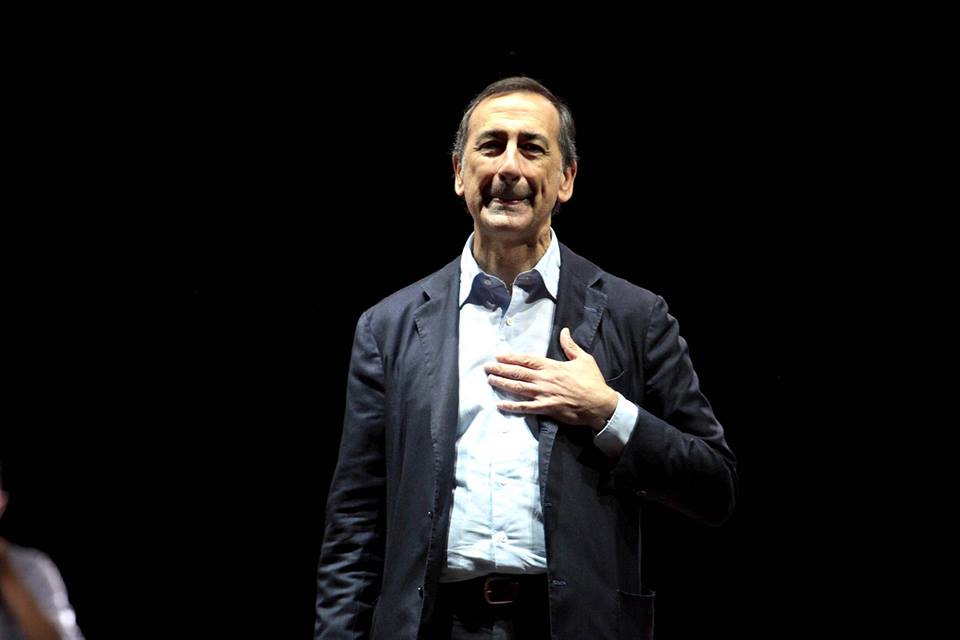

Like with all local elections, there were bright spots for the governing party. In Italy’s financial and fashion capital of Milan, Beppe Sala, the PD’s star candidate — a figure closer to Renzi and the head of ltaly’s Expo World Fair last year — narrowly defeated center-right opponent Stefano Parisi by a margin of 51.7% to 48.3%.

In Naples, the largest city of Italy’s south, the left-wing Luigi De Magistris, a longtime (and anti-Renzi) rebel of the Italian left, and a former prosecutor, easily defeated Gianni Lettieri, the candidate of the center-right Forza Italia, with 66.85% of the vote, after pushing the PD into third place on the June 6 ballot. The race was a rematch of the 2011 race. De Magistris is a popular figure for his work as a prosecutor on several corruption cases in southern Italy, who began his career first as an elected member of the European Parliament in 2009.

The tradition of direct election for mayors is relatively new for Rome, but the first two elected mayors in Rome’s history both came from the left — Francesco Rutelli and Walter Veltroni — and both of them became popular national figures and potential prime ministers, though neither managed to lead the centrosinistra (center-left) effectively when given the chance.

Giachetti, PD’s candidate in Rome against Raggi, is vice president of the Chamber of Deputies, and he’s been a member of the Chamber since the 2001 elections. Giachetti, however, never quite managed to rise to the Rutelli-Veltroni level in terms of gravitas and charisma. But even if he had, it would have been difficult enough to blunt Raggi’s appeal.

Though it seems like a defeat today, by October, Renzi might ultimately come to have preferred the result in Rome’s elections today.