Donald Trump’s campaign to ‘Make America Great Again’ may be associated with halting immigration from Mexico or making deals with China, Russia or Japan. But a Trump administration might bring another country to the forefront of international relations. ![]()

![]()

That’s because his wife, Melania Knauss Trump (in Slovene, Melanija Knavs) would be only the second First Lady born outside the United States.

Louisa Adams, the wife of the sixth president, John Quincy Adams, was born in England. Teresa Heinz Kerry, a Mozambican-born American, the wife of US Secretary of State John Kerry, would have also been a foreign-born First Lady, had Kerry won the 2004 presidential election.

With a staggering victory in Florida’s Republican primary on Tuesday, Trump has amassed around 673 delegates to July’s Republican convention in Cleveland — more than half of what he’ll need to reach 1,237 and the nomination, and much to the horror of a shellshocked Republican Party that’s watched Trump attack Mexican immigrants as racists, called for a blanket ban on Muslims entering the United States, threatened to sue journalists and encouraged physical violence at rallies.

So, even as Trumpmania sweeps right-wing voters across the United States, is the country ready for a Slovene-born supermodel in the East Wing?

For a candidate whose approach to presidential politics is anything but ordinary, Melania Trump’s approach to the campaign trail has been equally unorthodox in a race pitting her against former US president Bill Clinton for the title of ‘first spouse.’

If Bill Clinton’s role in a Hillary-led White House remains something of a mystery, so does Melania Trump’s. She hasn’t identified any particular key issues that she would champion as First Lady, such as Laura Bush’s focus on education and literacy or Michelle Obama’s focus on childhood obesity and fitness. But that’s also because she is raising a 10-year old son, Barron, the youngest of Donald Trump’s five children across three marriages. There’s more than a murmur of talk that Donald Trump’s daughter Ivanka, would fulfill more of the traditional roles of the First Lady.

Regardless, Melania Trump would certainly bring a level of elegance to the White House unseen since perhaps the 1960s when Jacqueline Kennedy lived there. As American voters focus on a general election showdown between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, Melania Trump’s most important role could be humanizing and softening her husband’s image — he would enter the general election as the most unpopular major-party candidate in recent US history.

Born in 1970 in the small town of Sevnica in southeastern Slovenia, the 45-year-old Melania Trump, is the daughter of a fashion designer, which propelled young Melania’s own modeling career in Milano and Paris and, finally, New York City. She first met Donald Trump at fashion week in the autumn of 1998, and they married in 2005. To date, it’s been Donald Trump’s longest and, seemingly, most successful marriage. Although she became a permanent resident of the United States in 2001, she obtained her citizenship a decade ago in 2006.

But the 45-year-old supermodel, who has graced the cover of Vogue and GQ but not Time, is not exactly a ubiquitous presence on the campaign trail. She rarely makes speeches or gives interviews, though that has changed as Trump’s candidacy gained traction. The rapid transition from supermodel to campaign trail spouse hasn’t been incredibly easy. Most potential first ladies spend a lifetime in politics becoming just as savvy in politics as their spouses. Melania Trump, whose first language isn’t English, has had exactly nine months.

Moreover, when she has ventured into the media, she’s faced tough questions about her husband’s statements about women and his strong anti-immigration stands. In particular, she has faced criticism that as a European model, her path to American citizenship, which involved a special kind of H1B visa, has been far easier than most immigrants. In a debate earlier this month, Donald Trump appeared to soften his stand against the kind of H1B visas available to workers in high demand (including models), only to harden his stand again a day later.

But the nature of the modern presidency means that Trump’s nomination or, especially, a Trump victory in November, will bring Slovenia squarely into the center of American consciousness for, let’s face it, probably the first time in US history. It would be a surprise if many Americans could even place Slovenia on a map or even know that it’s part of what used to be Yugoslavia.

Television news crews have already started descending on Sevnica, a trickle that is likely to turn into a flood by the time of the July convention or, despite the terror of Democrats and more than a few Republicans, next January’s presidential inauguration.

More importantly for Slovenia, the rash of attention means that even if the Trump candidacy somehow fades this spring or falls short of 270 electoral votes in November, interest in Slovenia, including tourism from the United States, could skyrocket for years to come. Since 2012, The New York Times has published just four items in its travel section on Slovenia. It’s a smart bet that will change as the Trump narrative dominates headlines in 2016 and the American electorate gets to know Melania Trump and her background.

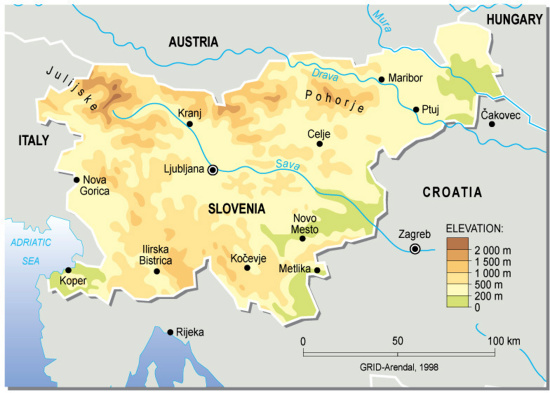

So where is Slovenia? And what do you need to know about it?

It’s a mostly landlocked country (it has just 46 kilometers of coastline along the Adriatic Sea), and it was once one of the most prosperous regions of what used to be Yugoslavia. It borders Italy, Austria, Croatia and Hungary.

It’s home to just over 2 million people, its population is comprised of more than 80% ethnic Slovenes, and an even larger proportion of the population speaks Slovene, though that number is declining as other Balkan minorities emigrate to Slovenia.

As revolution swept the eastern bloc countries of Europe in 1989 and 1990, Slovenia was no exception. After a ten-day war, Slovenia won its independence from the Yugoslav federation in July 1991. It which turned out to be a far easier split for Slovenia than for some of the other Balkan nations, and its relatively homogeneous population is one reason why it avoided the kind of civil strife that plagued Bosnia and Herzegovina and even Croatia.

That means that Slovenia brags the kind of economy that many other Balkan countries could only dream of. It doesn’t need Melania Trump or anyone else to ‘make it great again’ because, by European standards, it’s already a pretty great place to live. Of the six (or seven, including Kosovo) countries that emerged out of the former Yugloslav republic, Slovenia was the first to join the European Union, as part of the wider 2004 EU enlargement, and even today, it is joined only by Croatia, which joined the European Union only in 2013. EU membership for the other Balkan states and Albania is years, if not decades, away. In 2007, Slovenia became the first post-communist country to join the eurozone.

Slovenia’s nGDP per capita of around $21,000 (as of 2015, per the International Monetary Fund) means that it boasts, by far, the best standard of living of any of the former Yugoslav countries — its closest competitor is Croatia (around $11,500), and Serbia lags far behind (around $5,000). Indeed, by comparison, that’s a higher GDP per capita than the economies of Portugal, Greece or, for that matter, anywhere else in the former Warsaw Pact bloc. Befitting its legacy as the main supplier of electronic parts to the Cold War-era ‘Yugo’ model, the automotive industry still plays an important role in the Slovenian economy.

In the past quarter-century, personality has been just as important as ideology in Slovenian politics. It’s still a relatively conservative country, as voters demonstrated last December when they rejected same-sex marriage.

Slovenia is also no stranger to the kind of outsider politics that Donald Trump embodies. Most recently, in July 2014, Miro Cerar, a political neophyte, leftist attorney and professor and (perhaps most importantly) the son of an Olympic gymnast, easily won snap parliamentary elections under the banner of the Cerar Stranka Mira Cerarja (SMC, Miro Cerar’s Party). The SMC has since changed its name to the Stranka modernega centra (Modern Centre Party). Cerar succeeded the country’s first female prime minister, Alenka Bratušek, took power in 2013 after a prior government failed.

Like many countries in Europe, Slovenia has grappled with the challenge of processing an influx of Middle Eastern and African migrants throughout 2015. Donald Trump, who wants to build a wall along the southern US border with Mexico, might take some inspiration from Cerar, whose government closed the Slovenian border with Croatia and, last November, started building a barbed-wire fence along the Slovenia/Croatia border.

Compared to other countries, the list of famous Slovenes (and famous Slovene Americans) isn’t exactly long. The Communist leader of Yugoslavia until 1980, Josp Broz Tito, had a Slovenian mother. Hugo Wolf, the famous Romantic composer, spent most of his life in Vienna, but he was born in what was then called Windischgrätz, then a part of the Austro-Hungarian empire but today part of northern Slovenia near the Austrian border.

The mother of longtime US senator Tom Harkin of Iowa was a Slovene immigrant. So were the paternal grandparents of US senator Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota. As was the mother of former Ohio governor and US senator George Voinovich. The Miami Heat’s Goran Dragić, born in the Slovenian capital of Ljubljana, might be the most famous Slovene athlete, though he joins more than a dozen of NBA players not only from Slovenia, but also Serbia, Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Historically, the peak of Slovene immigration came in the wave of European migration in the 1880s and the early decades of the 20th century. By far, the Midwest (from Minnesota to Pennsylvania) and, in particular, Ohio, is home to the largest numbers of Americans of Slovene descent. Since 2004, Slovenia has been part of the NATO alliance with the United States, and the two countries enjoy a sleepy, if amicable, relationship.

But the prospect of a Slovene-born First Lady, however, would transform the bilateral relationship in wholly radical ways, improbably forcing Slovenia into the 21st century American imagination.

I wish they dont mention Yugoslavia and the balkan states so offten . That was yesterday . Iife is not only yesterday but a day before , a year before , centuries before . Fake news and byesed vies never end .