It’s tempting to argue that results from three state elections in Germany on Sunday spell the beginning of the end for chancellor Angela Merkel.![]()

In all three states, the eurosceptic, anti-immigrant Alternative für Deutschland (AfD, Alternative for Germany) won representation for the first time at the state level. That means that the AfD’s parliamentary presence will rise to eight German state assemblies, with the party poised to enter the Bundestag in the next federal election (after narrowly missing the 5% electoral threshold in September 2013).

* * * * *

RELATED: Kretschmann wins big in Germany’s prosperous south

* * * * *

It’s not the first time that radical parties have made minor gains in elections. In the 1992 Baden-Württemberg state elections, the hard-right Die Republikaner (Republicans) won over 12% of the vote, making it the state’s third-largest party. Hard-right parties have routinely won a small share of the national vote, though never enough to enter the Bundestag. Former East German communists founded what is today the radical leftist flank of Die Linke (The Left) and, despite a quarter-century from the fall of the Berlin Wall, the party (certainly not as hard-left as it was in 1989) is still controversial.

It’s true that Merkel has taken a bold stand in welcoming refugees from Syria and elsewhere in the Middle East and North Africa, and that policy has left many German voters concerned that the rate of immigrants — over one million since the migration crisis swelled last summer — is more than Germany society can assimilate culturally, socially and economically.

It’s not an unfair concern, so it’s not surprising that the AfD’s popularity is rising. Since its creation in 2013 as a party of mildly eurosceptic academics, it has turned sharply right under a new more hardline leader, Frauke Petry, a 40-year-old chemist and businesswoman whose anti-migration rhetoric has attracted voters scared of the effects of so many new German refugees. The AfD’s turn was so hard that Bernd Lucke, one of the movement’s founders, quit the party last summer.

The migration crisis may have been the impetus for the AfD’s emergence, but it’s no surprise that a right-wing alternative to Merkel’s Christlich Demokratische Union (CDU, Christian Democratic Union) is coming into view. She has become Germany’s most dominant politician in a generation by occupying virtually all of the ideological territory on the center-right and the center-left, leaving her right flank somewhat unprotected.

Hugging the center-left Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD, Social Democratic Party) into two grand coalitions since 2005, she’s shown a willingness to poach its most popular policies, including a raise in the German minimum wage. She’s been at the center of difficult battles to keep the European Union united, including last summer’s near-disastrous negotiations to keep Greece in the eurozone. The effect has been that more moderate voters have flocked to the CDU — so much so that she nearly won a remarkable absolute majority in the Bundestag in September 2013.

But it also means that voters who want change are turning not to the CDU’s junior coalition partner, the SPD, but to fringe groups, including the AfD. While the AfD’s gains are real, and they shouldn’t be ignored, neither should they be overstated. Far-right politics in Germany have existed for years, and while it’s true that the AfD clearly took votes from the CDU in Sunday’s state elections, it also appears that the AfD draws from far-left voters in eastern Germany and from disaffected SPD voters in western Germany.

The three states that held elections on March 13 couldn’t be more different, and it’s a risk to make blanket statements about the future of German politics through generalizing the results of Sunday’s elections.

Taking them one by one shows that, though the AfD risk is real, the electorate remains by far in favor of Merkel’s moderate approach to governance.

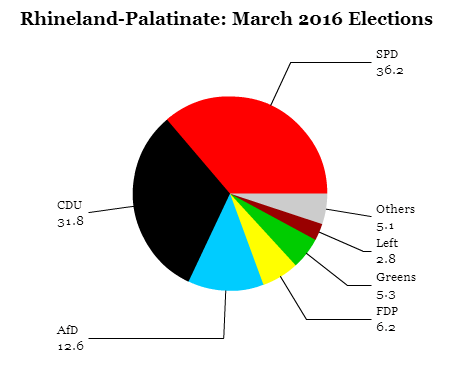

Rhineland-Palatinate, a southwestern state of arou nd 4 million people, borders Belgium, northern France and Luxembourg. For three decades, it has been an SPD stronghold, and it’s an export-heavy state that produces some of the best German wines, and it’s home to a lot of manufacturing of everything from glass products to automobile products. Here, SPD leader Malu Dreyer held off the CDU and, while the AfD won 12.6% of the vote, the SPD and CDU together won 68% of the vote. That’s hardly an upending of the status quo, considering both are part of the national government.

nd 4 million people, borders Belgium, northern France and Luxembourg. For three decades, it has been an SPD stronghold, and it’s an export-heavy state that produces some of the best German wines, and it’s home to a lot of manufacturing of everything from glass products to automobile products. Here, SPD leader Malu Dreyer held off the CDU and, while the AfD won 12.6% of the vote, the SPD and CDU together won 68% of the vote. That’s hardly an upending of the status quo, considering both are part of the national government.

Notably, the center-right, liberal Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP, Free Democratic Party), Merkel’s coalition partner between 2009 and 2013, returned to the Landtag after losing all of its seats in the prior election. The FDP’s success in Rhineland-Palatinate and in Baden-Württemberg is a sign that they could return to the Bundestag in the 2017 elections.

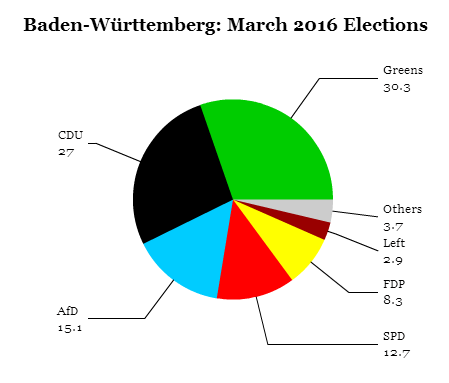

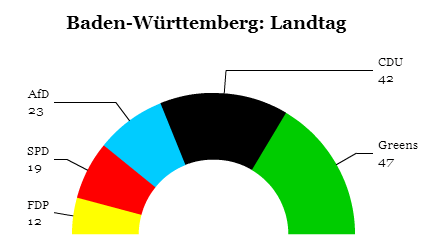

Baden-Württemberg, by far the largest prize with 10.6![]() million voters, has the lowest unemployment rate in Germany (4.0%), and it’s home to Daimler, Porsche and software manufacturer SAP. Here, for the first time in postwar history, the CDU didn’t finish the election as the top-ranked party, falling behind the Die Grünen (The Greens) of the wildly popular incumbent minister-president, Winfried Kretschmann, whose stand on migration was far more in line with Merkel’s approach than the approach of the CDU’s state-level leader.

million voters, has the lowest unemployment rate in Germany (4.0%), and it’s home to Daimler, Porsche and software manufacturer SAP. Here, for the first time in postwar history, the CDU didn’t finish the election as the top-ranked party, falling behind the Die Grünen (The Greens) of the wildly popular incumbent minister-president, Winfried Kretschmann, whose stand on migration was far more in line with Merkel’s approach than the approach of the CDU’s state-level leader.

The SPD fell behind the AfD to fourth place, though that had as much to do with the Green surge as with the AfD’s support. That means that Kretschmann may have to look to the FDP or even the CDU for a new majority, But together, the three parties and the FDP won over 78%, a resounding vote for mainstream parties.

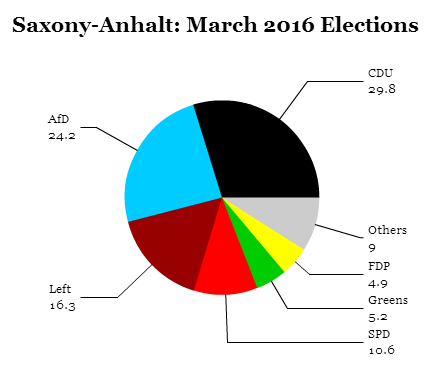

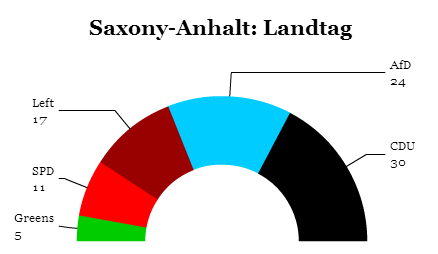

The AfD’s best result came in Saxony-Anhalt, the ![]() sole eastern state to vote in Sunday’s elections. Though it was expected to win up to 18% of the vote, its 24% support was far beyond what anyone expected, and well within single digits of the CDU, which governs in a grand coalition with the SPD. The CDU will now have to look to the Greens as well as the SPD for majority support.

sole eastern state to vote in Sunday’s elections. Though it was expected to win up to 18% of the vote, its 24% support was far beyond what anyone expected, and well within single digits of the CDU, which governs in a grand coalition with the SPD. The CDU will now have to look to the Greens as well as the SPD for majority support.

But though the AfD’s rise in the east is perhaps much more alarming, it’s due less to poaching the CDU’s traditional conservative voters and instead from stealing votes from the left-wing electorate. The swing away from the CDU was just 2.7%, but the swing away from the SPD was 10.9% and from the more radical Linke 7.4%. Though it has a small population, just 2.2 million, Saxony-Anhalt has one of the highest unemployment rates in the country. It’s a not-subtle reminder that the SPD, locked into a national coalition with Merkel and sharing much of the same economic policy, migration policy and EU policy, faces perhaps a greater crisis in the years ahead, as it struggles to articulate a cohesive center-left alternative to Merkel’s consensus approach.