Bernie Sanders might just be the American version of Jeremy Corbyn after all. ![]()

On the eve of Sunday night’s Democratic presidential debate, Sanders, the Vermont senator with a self-proclaimed ‘democratic socialist’ charge to win the Democratic presidential nomination, released a more detailed plan for achieving universal health care. By its own terms, the Sanders plan would provide ‘Medicare for all,’ though it actually goes much further by eliminating co-pay and deductibles, adding to the sticker shock of a federal program that would cost $1.38 trillion annually. It also comes with huge tax increases that would give US citizens, in one fell swoop, higher tax rates than many ‘social welfare states’ in western Europe.

Many critics, including those on the left who should be sympathetic to achieving even more universal health care, have been skeptical.

Ezra Klein at Vox chides the Sanders plan for omitting details about how a single-payer system would be forced to deny many benefits and treatments, just as Medicare does today. Paul Krugman at The New York Times calls the Sanders plan an exercise in fantasy budgeting, arguing that it relies on wild assumptions about the savings it can achieve in health care spending through a single-payer system. Jonathan Chait at The New Yorker argues that the next president will invariably face a Republican-controlled House (if not Senate) and that introducing a single-payer system would be impossible.

All of these are valid, reasonable criticisms of the Sanders plan.

But if you really believe that president Barack Obama’s health care reforms are just one step on the way to universal health care and, like Sanders, you are committed to a single-payer system, there was always a much better policy plan:

Lower the eligibility age of Medicare from its current level (65 and older) to allow all Americans aged 55 or older to participate.

It could have been, for Sanders, a beautiful political maneuver that would put both his rival for the Democratic nomination, Hillary Clinton, and congressional Republicans on the defensive, all while having the benefit of being generally great policy.

Let’s examine the policy brilliance first.

Health care economics in the United States became so skewed for two important reasons.

The first is that the market for catastrophic care doesn’t function like a real market in the classical economic sense. If I’m having a heart attack, I can’t shop around for 20 cardiologists and make an informed choice with the full leisure of time. Moreover, there’s a tragic lottery aspect to cancer, HIV/AIDS and many other long-term chronic diseases, so the insurance model makes sense, at least for health problems that require extensive or lifetime care. Insurance, whether government-mandated or not, makes a lot of sense, in the same way that we use insurance to smooth all kinds of risks from house fires to car accidents to unemployment.

The second is that the market for all other forms of ‘normal’ health care became so skewed. It’s no longer a two-party transaction between a doctor and patient, but at least a four-party transaction among a patient, an employer, an insurance company and the doctor. Historically, that means artificially limited choice, all while driving up the bureaucratic costs of everyday care.

Obamacare has, to some degree, decoupled health care from employment. It has meant access to health care for some 20 million Americans who previously lacked insurance. But as the health care exchanges become more efficient, there’s every reason to believe that Obamacare will continue to undermine the role of employers in individual health care (in part, a result of wage freezes during Franklin Roosevelt’s presidency that forced employers to compete for workers through other benefits and incentives).

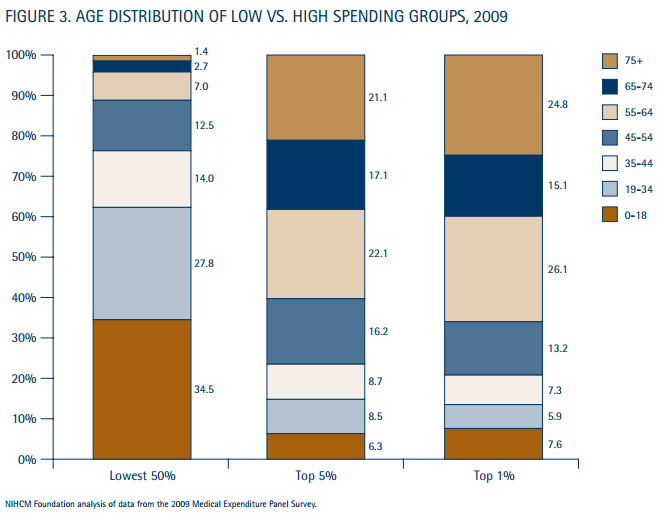

By reducing the eligibility age for Medicare, however, Sanders would remove from the private-sector health care pool an age bracket that has, by far, the highest health care costs (after the 65-and-older group, which is of course already covered currently by Medicare):

The result isn’t just to extend a single-payer system (through Medicare) for another 10 years of life, when health care costs are often far greater than at age 25, or 35, or 45. It means that premiums could fall further for the remaining 25-to-55-year group that will be looking for health care on the Obamacare exchanges, whose success will only uncouple employment and health care. That, as Obamacare’s advocates have argued, creates more incentives for working-age Americans to take more entrepreneurial risk because leaving a job for a start-up no longer means giving up health care. (Exactly as Republicans argued when Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney introduced a statewide plan in 2006).

It’s also not a new idea.

Throughout the first year of the Obama administration, it floated from time to time as an alternative to a single-payer system, though Connecticut senator Joseph Lieberman’s decision to oppose lowering the Medicare eligibility age seemed to kill it in December 2009. It reemerged a month later after Republican challenger Scott Brown unexpectedly won the January 2010 race to fill the seat of the late Edward M. Kennedy. Ultimately, Obama pushed ahead for the health care reform in the form of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act that he signed into law just two months later in March 2010. As vice president Joe Biden said, it was, in fact, a ‘big fucking deal.’

For now, Sanders’s appeal hasn’t been dented — he has a genuinely strong chance at an upset victory in the February 1 Iowa caucuses and he’s now the favorite to win the February 8 New Hampshire primary. His ability to win South Carolina, Nevada and other contests later in February and March, however, seems slimmer.

But by supporting ‘Medicare for 55-and-older,’ instead of ‘Medicare for all,’ Sanders would have done at least three things. First, he would have remained firmly to the left of Clinton on health care reform, and no one disputes his sincerity or his long-term commitment to a national single-payer system. Second, he would have inoculated himself from the Clinton campaign’s charge that his ‘Medicare for all’ plan not only ignores Obamacare’s progress but (somewhat more dubiously) actively endangers Obamacare. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, it would signal to undecided voters and to media influencers that Sanders is actually prepared to be president, not just to lead a movement on the far-left flank of the Democratic Party. Sanders has every right to defend the idea of a single-payer system, but it’s not going to happen in a Sanders administration, short of a miraculous turnaround in congressional voting patterns that long predate the 2010 midterms that restored Republicans to House control.

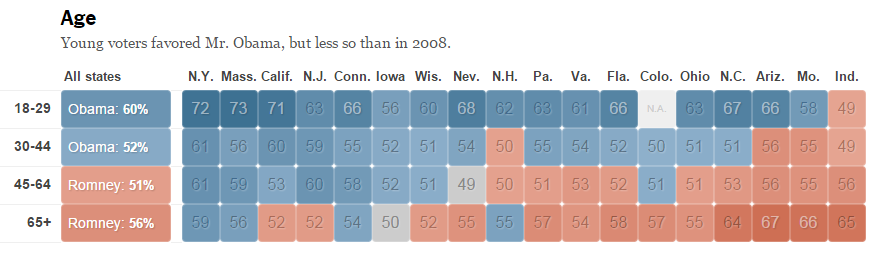

What makes the ‘Medicare-for-55-and-up’ alternative so brutally effective as a political salvo is that it would force Republicans to engage on their own turf. Today, the Republican coalition is chiefly white, rural and suburban and Christian. But it’s also much older. In the 2012 presidential election, Romney performed better among older voters, according to exit poll data:

While Romney did best among the 65+ crowd, he also won the 45-to-64 demographic (however narrowly) nationally and in even in some surprising swing states, like Florida, Virginia, Pennsylvania, Ohio and New Hampshire.

If, in early 2017, a president Sanders takes a single-payer bill to the Congress, it will be a risible non-starter. If, however, he introduces a bill extending Medicare coverage to a crucial demographic for the Republican Party, it would be much, much harder for House Republicans to oppose — for the same reasons that Bill Clinton used the fear of Republican cuts to the growth of Medicare in 1995 and 1996 to savage House speaker Newt Gingrich and, by extension, Senate leader and his eventual 1996 Republican opponent, Bob Dole.

Sanders might even be able to push reforms one step farther and argue for consolidating various federal plans into one larger, cost-saving ‘Super Medicare’ (for seniors, for veterans, for federal workers, for children, perhaps even incorporating Medicaid for the poor).

In a world with executive-legislative deadlock on the horizion, a Sanders administration would have to take its victories where it can find them. His platform includes a lot of leftist priorities. A large wealth tax designed to reduce income inequality. A hike in the national minimum wage to $15. A massive reform of student debt burdens. Tighter regulations on the finance industry. These may or may not be wise policy goals. But none of them seem remotely possible with a Republican-controlled House. With his health care plan, in particular, Sanders seems content to forego what little remains of the low-hanging fruit of potential legislative victories.

Even if he wins both Iowa and New Hampshire, Sanders will still be left campaigning in places like South Carolina, Florida, Texas and Michigan on a Pollyanna single-payer plan that would be (excuse the pun) dead on arrival.

But there was always a much shrewder alternative, and it’s a missed opportunity that may have cost Sanders his last chance at rising to the level of presidential credibility.