Forget Scotland or Catalonia. Forget Wallonia and Flanders. Forget the Basque Country or Republika Srpska.![]()

![]()

The hot separatist movement in 2016 might be in Corsica, the French-controlled island where Napoleon Bonaparte was born and which sits roughly 100 miles off France’s southeastern coast.

Corsica’s rising nationalist tide might this year outshine Catalonia, where a new regional government with a mandate to seek independence was sworn in last week, and Scotland, where the Scottish Nationalist Party hopes that local elections in May will boost its hold on the regional parliament and advance a fresh independence referendum.

For the first time, an explicitly nationalist coalition now controls Corsica’s regional government after it unexpectedly triumphed in December’s regional elections. That’s exactly one more region than the far-right Front national controls, despite the hype that Marine Le Pen and her allies could take power in up to six of France’s 13 newly consolidated ‘super-regions.’ A movement that has long been fragmented into myriad camps and ideologies, often violent, is now more united than ever and committed to political engagement.

* * * * *

RELATED: Why isn’t separatism or regionalism more dominant in the politics of Bretagne?

* * * * *

Once rooted in political terrorism, Corsican nationalism has now turned to a more peaceful approach that appears to be attracting larger numbers of voters. Though the origins of Corsica’s unique regional flag, featuring a Moor’s head wearing a white bandanna, may be lost to the puzzles of history, it is nonetheless as much a symbol of the Corsican nation as the Scottish saltire.

Shortly after regional elections, when a wave of violence against immigrants (including an attack on a Muslim prayer room) threatened to mar the new nationalist government, its leaders united to decry the violence, blaming it on the anti-Muslim rhetoric of the Front national. Though the incident raised tensions between Corsican nationalists and prime minister Manuel Valls, who clumsily reiterated state’s control over Corsica and sent France’s interior minister Bernard Cazeneuve to the Corsican capital of Ajaccio, the unrest subsided soon after the new year.

Corsica’s new regional government will have two years to demonstrate that it can maintain its united nationalist front, provide capable governance and credibly advocate for greater Corsican autonomy. For the first time in years, Corsica’s status might even become an important issue in the upcoming 2017 presidential election.

Most importantly, if 2016 does become a breakout year for Corsican sovereignty, it will reinforce separatist trends not only in Scotland and Catalonia, but across Europe, catalyzing autonomy movements both familiar (e.g., Transnistria, Flanders and Kurdistan) and novel (Bavaria, Sardinia and Russian-majority parts of the Baltic States).

Corsica — a small island with a long history

Corsican sovereignty might not top the list of pressing European policy matters. But it’s an island with a long history, controlled by the Greeks, the Romans and many others from antiquity through the present day. For nearly 400 years from 1284, it was ruled by Genoa, the Italian city-state, until Corsican nationalists won independence in 1755.

Pasquale Paoli, who drove the Genoese from the island, established an Enlightenment-influenced government, with a written constitution, universal suffrage for men and women and parliamentary rule, and Paoli remains a Corsican hero despite the republic’s fall to France in 1769. France has controlled the island ever since, bringing it under the thumb of one of Europe’s most consistently centralized national governments. Compared to the United Kingdom, Germany or even Italy or Spain, the central government in Paris has long been reluctant to cede power to France’s regions, including one as idiosyncratic and sometimes turbulent as Corsica.

For Paoli’s descendants, the dream of an independent Corsica isn’t necessarily so farfetched. Poland, for example, lost its sovereignty for centuries — the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth collapsed in 1795, a short-lived Polish republic from 1918 to 1939 was soon overrun by Nazi Germany and a postwar Polish republic remained a Soviet satellite until 1989.

Corsica’s population of around 325,000 is about the same as Iceland and just a bit less than Malta. The island has its own indigenous language, Corsu, which is more closely related to the Tuscan dialect of Italian than to French and, indeed, Corsica lies far closer to the Italian mainland and the Italian island of Sardinia than to the French mainland. Only around two-thirds of Corsica’s population can speak Corsu, however, and the French language, universally spoken by all Corsicans, has long dominated official matters, education and public life.

Traditionally, the Corsican nationalist movement shared more in common with the Basque Country’s Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) or Northern Ireland’s Irish Republican Army (IRA) than with the political separatists of Scotland or Catalonia. The Fronte di Liberazione Naziunale Corsu (FLNC, National Liberation Front of Corsica), formed in the mid-1970s as a militant force to demand independence, quickly became a leader in western European political violence. Among its most popular attacks were those on chiefly vacant second homes owned by French mainlanders who vacationed along the Corsican coast, also a symbol of France’s disregard for local Corsican culture and autonomy. But the FLNC, over the years, came to behave like an organized crime operation, using its political goals as a racket to demand protection money — or ‘revolutionary taxes’ — from Corsican business owners.

Throughout the 1990s, Corsican attacks reached their apex, including the 1998 assassination of the sitting prefect, France’s representative in Corsica, Claude Érignac.

Though Corsica, like all of France’s regions, elects its own regional assembly, the local government’s powers are relatively weak, despite a wave of autonomy granted in the 1980s under leftist president François Mitterrand. In the wake of the 1990s attacks, center-right president Jacques Chirac reluctantly joined forces with his center-left prime minister Lionel Jospin to craft an attempt at broader devolution of regional power to Corsica through the Matignon accords. A series of bungled policies and operations in Corsica, however, helped erode Jospin’s popularity nationally, and Jospin’s own interior minister, Jean-Pierre Chevènement, indignant at responding to political terrorism by handing over ever greater powers, resigned in 2000 over the Matignon accords.

After Chirac’s reelection in 2002 (and Jospin’s humiliating first-round defeat), he introduced new propositions for autonomy, though the Corsican electorate narrowly rejected them in a 2003 referendum by a margin of 51% to 49%. Among the reasons for the Corsican ‘no’ vote may have been the government’s heavy-handed arrest of goat-herder Yvan Colonna, Érignac’s assassin, on the day before the plebiscite. At the time, it was a rare setback for Chirac’s new, hard-charging interior minister, Nicolas Sarkozy.

Why Corsica’s separatist moment could finally be arriving

In 2014, long after it began a terminal decline in popularity, the FLNC followed the lead of both the IRA and the ETA in declaring a unilateral ceasefire. In the meanwhile, however, political groups had overpowered the FLNC at the center of the Corsican nationalist movement. But infighting among Corsican groups, including the lingering remnants of the FLNC, kept the nationalist cause divided as a political matter.

Nevertheless, the disparate elements and ideologies that exist along the spectrum of Corsican nationalism have been gradually consolidating. In 2009, three nationalist groups combined to form Corsica Libera (Free Corsica), a hard-left party with the explicit goal of Corsican independence. In the meanwhile, a new party emerged, Femu a Corsica, that prioritized greater regional autonomy over independence.

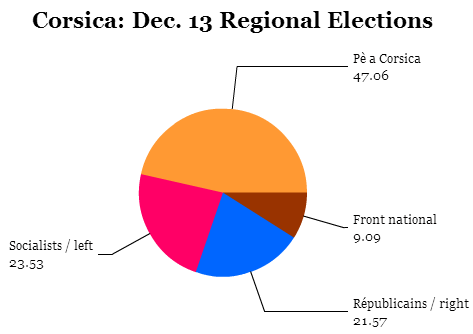

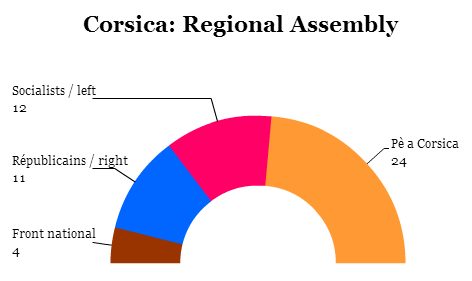

With the cessation of the FLNC’s armed conflict two years ago, the 2015 regional elections were the first set of elections where Corsican nationalism wasn’t defined by violence, radicalism and racketeering. Moreover, the pro-independence Corsica Libera and the autonomist Femu a Corsica joined forces for the 2015 elections in an even broader coalition, Pè a Corsica, which ultimately won 24 of the 51 seats in Corsica’s regional assembly.

Corsica Libera‘s leader, Jean-Guy Talamoni, is now the leader of the regional assembly, while Femu a Corsica’s leader Gilles Simeoni, the mayor of Bastia, Corsica’s second city, heads the Corsican executive government. Whereas competing leaders of the Corsican nationalist movement once plotted against each other (or worse), Talamoni and Simeoni today hold more power leading a united nationalist government than they ever could have hoped to achieve as the heads of clannish sects. It helped, too, that the left’s standard-bearer, Paul Giacobbi, the outgoing head of the Corsican executive, was indicted for embezzlement in July.

The success of Corsica’s nationalists is both a lesson and a warning to Valls and president François Hollande. The rise of a coherent, popular and peaceful nationalist movement in Corsica gives France’s central government an opportunity to make real strides toward autonomy that could tamp down the flames of separatists and, once and for all, end the specter of political violence, to the benefit of Corsicans and mainland French alike. But it also weakens Paris’s iron grip, as a theoretical matter, on France’s regions, and other nationalists, including those in northwestern Bretagne, eastern Alsace or elsewhere in southern France, might soon demand more devolution as well.

We in County Nice have long demanded the teaching of Niçard and Italian in our schools due to their historical pre-eminence over French in our region. We have seen somewhat of a renaissance in learning these languages – although their use in official circles is limited. The growth in the advocacy for the teaching of these historical languages in schools and evening colleges serves as a proxy for cultural independence from France, if not full autonomy.