After holding a free and relatively trouble-free election on November 29th, Burkina Faso has elected a new, civilian president: Roch Marc Christian Kaboré.![]()

That, in itself, is a milestone for a country that has very little experience with democracy or even civilian leaders, and that just two months ago faced yet another militant coup designed to throw the country’s elections off track. Kaboré is just the second civilian Burkinabé leader since the country gained independence from France in 1960.

Supporters and opponents alike were celebrating in the streets of in Ouagadougou this weekend to mark the second fully contested election in the country’s post-independence history.

Kaboré’s election, however, is just the first step in what could still be a very troubled path to stronger governing institutions, committed democracy and greater development in Burkina Faso, a country of over 17 million people, though one of the world’s poorest (the International Monetary Fund estimates per-capita nominal GDP at just $631).

Burkina Faso’s latest political chapter began in October 2014, when long-serving president Blaise Compaoré fled from office in the wake of massive protests against his bid to win yet another reelection. Compaoré, then a young military leader, helped Thomas Sankara take power in a 1983 coup — only to force the leftist Sankara out in 1987, killing his once-close friend Sankara in the process and transforming Sankara into something of a martyr of the African left.

When Compaoré fled power last autumn, he was at the time the world’s seventh-longest ruling leader. Despite his autocratic rule at home, he had become an ally to the United States and to European powers at a time when west Africa has increasingly become a security concern for Western governments anxious to halt the rise of radical jihadist groups from Nigeria to the Sahel. The election comes in the aftermath of a deadly terrorist attack in Bamako, the capital of Mali, Burkina Faso’s neighbor to the north and the west. But the election also comes after the peaceful reelection of Ivorian president Alasanne Ouattara and ahead of scheduled Ghanian elections in 2016.

Compaoré today remains in exile in Côte d’Ivoire, but presidential military forces loyal to Compaoré staged a short-lived coup in September, postponing the current elections (then scheduled for October 11) and demonstrating the transitional government’s fragility.

Excepting the September coup attempt, Michel Kafando, the country’s ambassador to the United Nations between 1998 and 2011, has served as Burkina Faso’s president, often clashing with Isaac Zida, the acting prime minister and the military leader who took power in the immediate aftermath of Compaoré’s resignation. Tensions ran high consistently throughout the transition period, especially after the transitional government tried throughout the spring and summer to ban Compaoré’s former supporters from running in the October elections.

Nevertheless, in the current election, it was impossible to escape Compaoré’s legacy. Both major candidates have long records as officials throughout Compaoré’s 27-year reign.

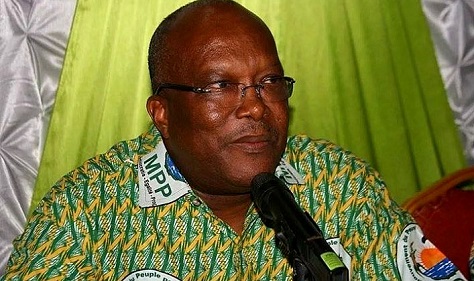

Kaboré served as a minister in Compaoré’s regime as early as 1989, served as prime minister from 1994 to 1996, and he was a longtime president of the country’s national assembly, from 2002 to 2012, also serving as the president of the ruling Congrès pour la Démocratie et le Progrès (CDP, Congress for Democracy and Progress). Long known as the ‘dauphin de Blaise,’ Kaboré left the CDP only in early 2014, in opposition to Compaoré’s push to change the constitution to run for yet another presidential term, and he founded a new party, the Mouvement du Peuple pour le Progrès (MPP, the People’s Movement for Progress) alongside former minister Salif Diallo and former Ouagadougou mayor Simon Compaoré.

His father, Charles Bila Kaboré, was a government official in the 1960s and 1970s, serving as finance minister, interior minister and other roles in what was then known as the Republic of Upper Volta (only renamed to Burkina Faso in 1984 under the Sankara administration).

His main opponent in the election, Zéphirin Diabré, is a former finance minister who served in several technocratic roles both at home and abroad and who left the CDP in 2010 to form the Union pour le Progrès et le Changement (UPC, Union for Progress and Reform). Diabré served for years in the United Nations in New York and, later, in the private sector in France.

Kaboré’s first-round presidential win, in part, reflects that he has been at the heart of power in Burkina Faso for decades, building his own domestic power base while Diabré was serving abroad.

In the elation of Kaboré’s victory, there are high hopes that the election will mark the first step to the kind of democracy that Ghana, Nigeria and other countries in west Africa have built and strengthened in recent years. But given Kaboré’s ties to the ancien régime, it is too soon to whether he can become the kind of leader to advance that kind of rupture with an often bloody and discouraging past. If Kaboré turns out to be just as autocratic as his predecessors, the MPP could become just the latest iteration of the CDP. If Kaboré really does try to change the Burkinabé political culture, he could face a backlash from the Compaoré-era elites and even another coup. Though the elite presidential guard, the Régiment de sécurité présidentielle (RSP, Presidential Security Regiment), was officially disbanded after its September putsch attempt, there’s no shortage of potential troublemakers.

Voters also chose the 111 members of the unicameral Assemblée nationale (National Assembly). Though the results of the parliamentary elections are yet to be announced, the MPP may not control an absolute majority, and it was expected to face stronger competition from both the CDP and other opposition parties.