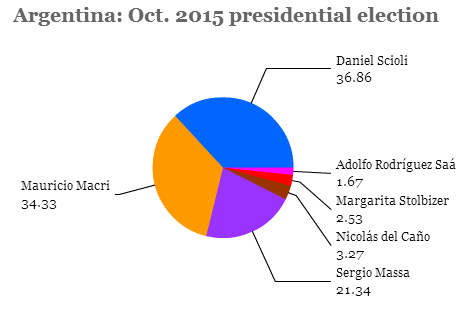

When Daniel Scioli emerged on Sunday night to declare victory in the first round of Argentina’s presidential election, it was clear that he did not expect to win the presidency outright and that he would face a runoff — even though no official election results were yet announced.![]()

When the first results finally came at around 11 p.m., they showed a far closer race than anyone predicted. At one point, Scioli’s rival, outgoing Buenos Aires mayor Mauricio Macri, was actually leading Scioli. Ultimately, Scioli narrowly won the presidential election’s first round, but Macri’s support was so unexpectedly strong that he now enters the presidential runoff campaign as the odds-on favorite to end 12 consecutive years of kirchnersimo.

At stake in the presidential showdown is the legacy of one of the most important bastions of Latin America’s populist, statist left.

Macri, the candidate of the center-right Cambiemos (Spanish for ‘Let’s change’) coalition, has gradually expanded a political movement that was once limited to just the most affluent corners of Argentina’s capital. The son of an Italian immigrant, Macri joined his father’s business in the automobile sector before becoming the president of the popular Boca Juniors football club. He first entered politics in 2003, waging a failed run to become mayor of Buenos Aires. He lost that race, but he used the experience to form a new urban, liberal political party, Propuesta Republicana (PRO, Republican Proposal) in 2005 and, two years later, he won the mayoral election.

* * * * *

RELATED: Kirchner 2019 comeback could

complicate Scioli presidential bid

* * * * *

As the standard-bearer of the Cambiemos coalition, he merged his own Buenos Aires-based movement with the Unión Cívica Radical (UCR, Radical Civil Union), a long-lived liberal party that has stood as a contrast for decades to the dominant left-wing populist peronismo. Most voters believe that Macri is the candidate most likely to lift capital controls and bring Argentina back into global debt markets, even if it means a peso devaluation and strong measures to tamp down inflation. Nevertheless, with economic neoliberalism still widely discredited after the economic crisis of 1999-2001, Macri has taken efforts to reassure that he will not subject the Argentine economy to immediate radical change, and he’s even gone out of his way to praise the values of peronismo.

Despite doubts, the Macri campaign’s plan seems to be working. He swept the city of Buenos Aires, along with the provinces of Mendoza, Córdoba, Santa Fe and Entre Rios in Sunday’s vote.

His success in Sunday’s general election took Argentines somewhat by surprise. When election day began, it was conceivable that Scioli, a former vice president and currently the governor of Buenos Aires province, might have scored a first-round victory in the presidential race. He boasted the support of outgoing president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and the governing Frente para la Victoria (FpV, the Front for Victory), an electoral coalition anchored by Argentina’s peronista ‘Justicialist’ Party. A former motorboat racing star, Scioli took a lead in polls early in 2015, and he’s consistently held an advantage to become Argentina’s next president. Despite rampant inflation, health scares, political intrigue and a slowing economy, Kirchner’s approval ratings have generally improved over the course of the last year — so much so that everyone expects her to try to return to the Casa Rosada in the 2019 election. Most recently, in Argentina’s compulsory open presidential primaries on August 9, Scioli won 38.4% of the vote versus just 30.1% for Cambiemos.

What a difference two months can make. Continue reading Macri, Argentine opposition flex muscle as November runoff looms