Roughly speaking, there are three plausible outcomes from tonight’s Canadian federal election.![]()

The first, increasingly likely (with a final Globe and Mail poll giving the center-left Liberal Party a lead of 39.1% to just 30.5 for the Conservative Party), is an outright Liberal majority government. It’s a prospect that no one would have expected a few days ago and certainly not when the campaign began with Liberal leader Justin Trudeau stuck in third place. But as the Liberals have pulled support from the New Democratic Party (NDP) and possibly even from the Conservatives in the final days of the campaign, they just might make it to the 170 seats they’ll need to form a government without external support.

The second, increasingly unlikely, is a Conservative win. No one expects prime minister Stephen Harper to win a majority government again nor anything close to the 166 seats he won in the 2011 election (when the number of House of Commons seats was just 308 and not yet the expanded 388). Under this scenario, Harper would boast the largest bloc of MPs, even though an anti-Harper majority of NDP and Liberal legislators would be ready to bring down Harper’s shaky minority government on any given issue. Despite a growing Liberal lead, there’s some uncertainty about the actual result. That’s because Canada’s election is really 338 separate contests all determined on a first-past-the-post basis. In suburban Ontario, throughout British Columbia and in much of Québec, where the NDP is most competitive, left-leaning voters could split between the NDP and the Liberals, giving the Conservatives a path to victory with a much smaller plurality of the vote. (In the waning days of the campaign, several groups have tried to urge strategic voting to make sure the anti-Harper forces coalesce on a riding-by-riding basis).

The safest prediction is still a Liberal minority. For a party that currently holds just 34 seats in the House of Commons after former Liberal leader Michael Ignatieff’s 2011 disaster, a plausible increase of 100 seats would be a massive improvement, validating the Liberals’ decision to coronate Trudeau as the party’s last saving grace. Despite the NDP’s loss of support, it is still expected to have some resiliency in British Columbia and Québec. Getting to 170 from 34 might just be a step too far, but it’s certainly no failure if Trudeau falls short in just one election cycle.

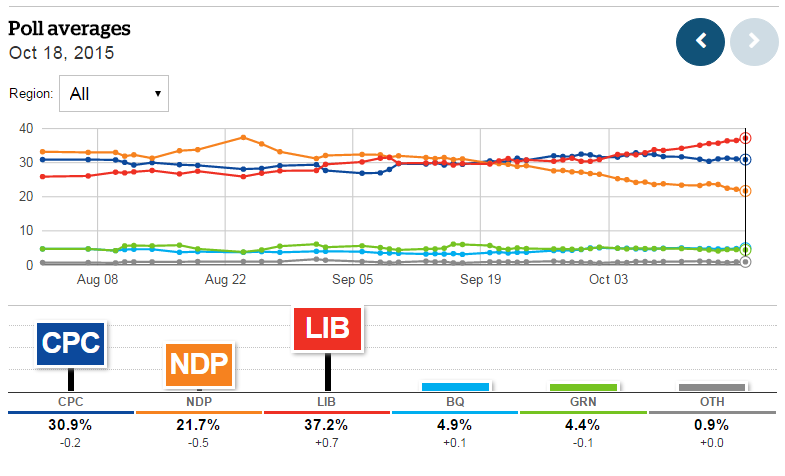

What seems clear from the trajectory of Canada’s 42nd election campaign is that Canada’s two parties of the center-left easily attract in aggregate over 50% of the vote in national polling surveys. Together, their lead over the Conservatives isn’t even close. Over the past month, as the Liberals have gained support, it’s chiefly come at the expense of the NDP, which was winning many more of those centrist and left-leaning voters at the beginning of the campaign:

As the Liberals gained, the NDP correspondingly lost support, indicating that the fluidity in the election has come from anti-Harper voters shopping for the most attractive alternative.

In the second two scenarios above, the most natural result would be a Liberal-NDP coalition. Given the fatigue with three consecutive Harper-led governments, the political gravity of such an outcome feels nearly inevitable. If the Liberals win a minority government, it seems natural that another broadly progressive party would support them or even join Trudeau in coalition. You might expect the same outcome even if Harper wins a minority government. Shortly after the election, the NDP and Liberals would engineer a vote of confidence that brings down the curtain on the Harper era.

What’s more, both Trudeau and Mulcair agree that displacing Harper is their top goal in 2015, and Mulcair has declared there’s ‘not a snowball’s chance in hell’ that he would prop up a Tory minority government. That wasn’t always necessarily the case. Mulcair, comes from the center-right wing of the NDP and who served as an environmental minister in the provincial Liberal government of former premier Jean Charest (once upon a time the leader of the national Progressive Conservatives) and he even considered joining the Conservatives when he made the leap from provincial to national politics a few years ago. But the Conservative attempt to use the niqab as a cultural wedge issue to attack Canada’s Muslim minority, in particular, dismayed Mulcair in the final weeks of the 2015 campaign.

Nevertheless, it’s… complicated. For a lot of reasons.

The Liberals and the NDP have a long-shared and mutual antipathy to coalition. For decades, when the NDP was little more than a gadfly on the progressive and socialist left that sometimes scored a victory at the provincial level, that wasn’t a problem. But the NDP’s emergence as a potential party of government under the late Jack Layton in 2011 and under Mulcair in 2015 has highlighted the problem. Progressive forces are losing seats to the Conservatives so long as voters are still divining their support between the two leftist alternatives.

Harper has often used the spectre of coalition politics as a bogeyman, though there’s not really any constitutional basis for it. When it comes to working together to force Harper out of office, Canada already has a precedent — and it’s not particularly pretty. In 2008, the NDP and the Bloc québécois (BQ) joined forces with the Liberals, then under the leadership of Stéphane Dion, to form a coalition government. Harper, fresh off a narrow victory in the October 2008 federal election, faced losing a vote of no confidence over a budgetary matter. Harper instead prorogued the government, essentially pausing all parliamentary activity for nearly two months. By the time that the parliament reconvened, the Liberals changed leaders and Harper had so toxified the idea of a coalition (including separatists at that) that the Liberals abandoned the idea and supported the 2009 budget. It was, perhaps, a constitutionally dodgy move on Harper’s part, but it worked — and it made ‘coalition’ a naughty word in the 2011 election.

But it’s even worse. Trudeau and Mulcair have often reserved the harshest criticism on the campaign trail for each other. On both substance and style, the two leaders don’t seem to care for the other very much. Given that the real fight in 2015 has been over whether the Liberals or the NDP are the superior alternative to Harper, it stands to reason that Trudeau and Mulcair are not on the best terms. For example, in a September debate, when Trudeau said that Mulcair’s platform amounted to ‘puffs of smoke,’ Mulcair abrasively said, ‘you know a little about that, don’t you, Justin,’ mocking Trudeau’s plan to decriminalize marijuana use. In another debate, Mulcair caustically compared Trudeau’s support of the Harper government’s anti-terrorism Bill C-51 to the civil liberties record of his father, Pierre Trudeau:

The same way the NDP was the only one to stand up to Pierre Trudeau when he put Canadians in jail without charges. The NDP stood up against that.

That means that it could take NDP grandees like former leader Ed Broadbent (who’s already calling for a coalition) and former Liberal prime minister Jean Chrétien to facilitate cooperation talks. Bob Rae, the former NDP premier of Ontario who served as interim Liberal leader from 2011 to 2013, might also have a unique perspective after giving the NDP’s support to Ontario’s Liberal premier David Peterson in the late 1980s.

But it might also take a different NDP leader to engineer an informal ‘supply’ arrangement or a more formal coalition, the latter bringing the NDP into federal government for the first time. Among the most likely successors is Nathan Cullen, an MP since 2004 from the Ontario riding of Skeena-Bulkley Valley. Though he finished in third place in the 2012 NDP leadership election, he was appointed as house leader of the official opposition in Mulcair’s shadow cabinet. Still a rising star at age 43, Cullen is a more traditional leftist, which makes him a better ideological fit with Trudeau, who outflanked the NDP on a more leftist economic plan.

A Liberal-NDP agreement might still be short-lived. Perhaps the NDP would sign up to Trudeau’s deficit-spending plan as an attempt to boost demand and jobs in the face of a growing economic recession. Mulcair’s support for balanced budgets always seemed more about conveying the NDP’s seriousness as a potential party of government than closely-held policy principle. But the NDP might also have strategic reasons to oppose a future Liberal attempt to approve the Energy East pipeline. Mulcair vociferously opposes the anti-terrorism bill that both Harper and Trudeau supported.

One of the first issues Canada’s next government will review is the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Harper’s government, joining the United States, Mexico, Australia, Japan and six other countries, finalized negotiations on the landmark trade deal earlier this month. Mulcair’s NDP is vehemently opposed to it, on the basis that it would destroy jobs throughout many Canadian industries. While Trudeau hasn’t taken a clear position on TPP, he’s made it abundantly clear that the Liberals are broadly pro-trade, and he’s questioned whether Canada can abandon a deal that both the United States and Mexico are joining. So even if the two parties agree on ousting Harper, it’s not clear how long their alliance would last if tested by the issue that arguably divides them most of all.