Sometimes, what doesn’t happen in an election matters more than what does happen.![]()

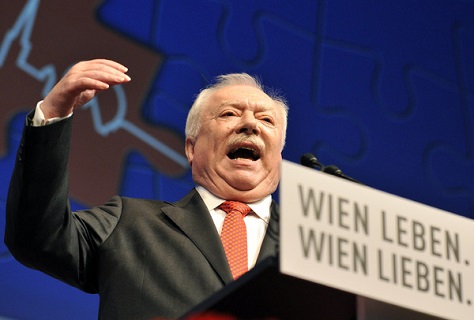

So it was in Vienna on Sunday, when Michael Häupl, the longtime center-left mayor held onto power. That’s not so surprising, because his Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ, Social Democratic Party of Austria) has controlled Vienna’s state government in every election in the postwar era.

What’s more, though polls showed that the far-right Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ, Freedom Party of Austria) was trailing the Social Democrats by just 1% in the week before Vienna’s elections, the Freedom Party actually lost by nearly 10%. Though the Freedom Party’s result marks a gain against its prior result in 2010, and its strength is growing amid the backdrop of Europe’s migration and refugee crisis, its failure in Vienna is notable.

After an election campaign that pitted Häupl in competition directly with the Freedom Party’s leader Heinz-Christian Strache, the far right’s failure to break through should come as a relief to Austria’s entire political mainstream, of both right and left. Had Strache won the election, it would have shaken the foundations of the grand coalition that governs Austria under Social Democratic chancellor Werner Faymann.

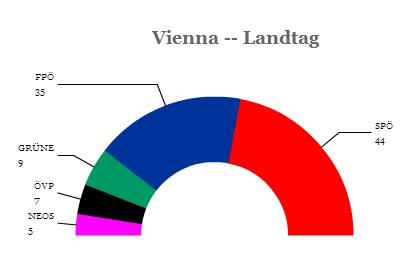

Vienna, aside from being Austria’s capital, is also the country’s largest state, with 1.8 million of Austria’s 8.6 million people, so elections for the Landtag invariably influence the national political climate. Die Grünen (the Greens/Green Alternative), the third-placed party, won enough seats to give the SPÖ-led coalition a majority in the state assembly.

With over 200,000 refugees settling this year in Austria (and many more expected to arrive), Strache and the Freedom Party have argued that Austria should take a harder line on accepting migrants, along the lines of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán or Slovakian prime minister Robert Fico. Over the weekend, alone, around 12,500 refugees arrived in Austria.

Strache, however, has moderated his party’s anti-immigration message by framing it more in terms of protecting Austria’s most vulnerable citizens, a populist message that de-emphasizes anti-Islam or nakedly anti-immigrant slogans that other far-right parties in France and The Netherlands have embraced. Instead, Strache talks as much about protecting jobs as anything else.

The Freedom Party’s resurgence follows the wild rise and fall of its mercurial late former leader, Jörg Haider, who led the party throughout the 1990s and even brought the party into government in 2000, a result that caused the rest of the European Union to sanction Austria. Though Haider stepped down as leader to assuage international concerns, he continued to direct the party until 2005, when he bolted to form an alternative party. Haider died in a automobile crash in 2008.

Strache, a one-time dental technician, succeeded Haider to the FPÖ leadership in 2005. In each subsequent election (in 2006, 2008 and 2013), Strache has increased the party’s share of the vote. At times, Strache, who posed nearly nude in the leadup to the 2013 national elections, has demonstrated some of the same eccentricity that Haider once displayed. Despite the disappointing result, he nevertheless came closer than any other challenger in any election since 1945 to dislodging the Social Democrats from control in Vienna. The Freedom Party currently leads polls by a healthy margin for the next national elections, which much be held before 2018. Faymann governs in coalition with the center-right Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP, Austrian People’s Party), and there are few countries in Europe with a stronger tradition of grand coalitions than Austria. Together, the two mainstream parties continue to win more support than the Freedom Party.

Two weeks ago in state elections in Upper Austria, the Freedom Party finished closely in second place behind the Austrian People’s Party, which has likewise governed in that state continuously since 1945.

Austria’s relatively young liberal party, the Das Neue Österreich (NEOS, The New Austria), won nearly 6% of the vote in Sunday’s Vienna elections, giving them five seats in the Landtag after they fell short in the Upper Austria elections. The party emerged as a new force, if still a limited force, in Austrian politics in 2013, when it won 5% of the national vote and nine seats in the Nationalrat (National Council). It followed up its successes in 2014 by winning 8% of the vote in the European parliamentary elections, and its breakthrough in Vienna will perpetuate its claim to right-leaning economic liberals and left-leaning social liberals alike.