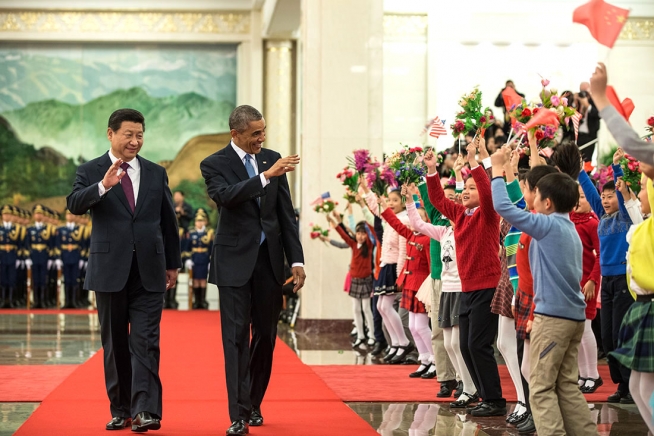

Despite the Fellini-esque excitement that swept the American capital over Pope Francis’s first-ever trip to the United States, it’s the arrival of China’s president, Xi Jinping (习近平), this week that will have the broader impact on global affairs.![]()

![]()

While the pope invoked human rights when he spoke about the environment in spiritual terms at the United Nations General Assembly Friday morning, Xi was preparing to announce that China would initiate in 2017 its own national cap-and-trade program, giving teeth to a pledge for carbon emissions in the world’s most populous country to peak in 2030, declining thereafter, part of an ambitious bilateral agreement signed between the United States and China last year.

It’s hard to think of two actors in international affairs who reside more starkly on the spectrum of ‘soft power’ and ‘hard power’ more than the two men who visited Washington this week. Francis, nominally the head of a country of less than 500 residents and 110 acres, leads a church with over 1.2 billion members, and he carries the moral authority with Catholicism’s believers to influence everything from LGBT rights to immigration reform. But Xi, as the leader of a country with 1.3 billion people, wields the political, military and economic power that comes from controlling the world’s largest economy and military force.

For all the talk about Francis’s ability to deploy soft power with tactical skill, it is Xi’s hard power that is setting the agenda for climate change policy around the world, and the dual contrast on Friday revealed the limits of soft power. There’s no indication that Francis’s exhortations have made any difference on the willingness of the Chinese government to embrace transformative environmental policy.

What’s more, Xi’s increasingly progressive stand on climate change isn’t driven by the desire for international praise or even necessarily the merits of a policy that will reduce global emissions, but by hard domestic politics. In a one-party state, the Chinese Communist Party knows that it ‘owns’ every problem in China (there’s no alternative Democratic or Republican Party it can blame), so Xi knows that his government has to be seen as doing something to ameliorate his country’s crippling and health-threatening pollution.

China’s orientation on climate policy is so important because it is responsible for the largest share (around one-quarter) of the world’s carbon emissions. But Chinese engagement is also so important because it helps solve the collective action problem that has hindered a truly global approach to reducing carbon emissions. For years, US policymakers have been able to shirk enacting any meaningful action because unilateral action would both impose additional costs on American businesses (that Chinese or Indian businesses would not have to incur). Moreover, unilateral American action would not even meaningfully reduce global carbon emissions because the United States today is responsible for around just 15% of the world’s carbon output.

China’s previous inaction didn’t stop the European Union, British Columbia or California from introducing their own cap-and-trade schemes, but early bipartisan hopes in 2009 for a national system in the United States dissipated, and former prime minister Tony Abbott actually repealed a carbon scheme introduced by Labor prime minister Julia Gillard in 2013.

Xi’s announcement is a game-changer because it eliminates everyone else’s excuse to drag their feet on designing their own cap-and-trade markets or imposing additional carbon taxes. In particular, China has argued for years, with some credibility, that American and European industrial development in the 17th and 18th centuries was not constrained by concerns over climate change, so it is unfair to hinder China’s development in the 21st century. Xi’s cap-and-trade program, however, yanks that same ‘catch-up’ excuse from India and sub-Saharan Africa.

Opponents in the United States may still prevent meaningful legislation for any number of reasons, but they will no longer be to do so by blaming China’s inaction (even though there’s reason to believe that the roll-out of China’s cap-and-trade program will not be entirely smooth, on the basis of pilot programs that China implemented across seven cities over the last four years).

As November’s pivotal climate change summit in Paris approaches, pressure will intensify on the United States as well as India, Russia and sub-Saharan Africa to introduce their own policies on climate change. That has absolutely nothing to do with Pope Francis — or feel-good bromides about a cleaner planet, Al Gore’s slide show, or even the scientific evidence that shows our planet really is gradually warming. Soft power is an important concept, and it still matters a great deal in shaping everything from human rights standards to refugee policy. But it’s old-fashioned hard power, based on cold-eyed domestic political considerations, that is propelling real action on climate change.