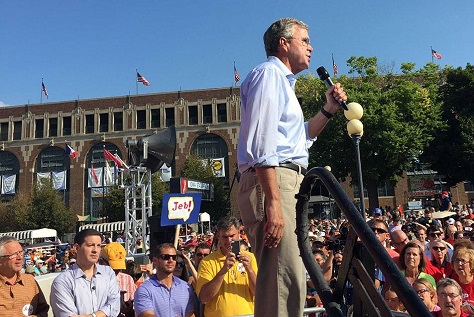

Last week, two of the leading contenders for the Republican presidential nomination delivered Major and Very Serious Foreign Policy Addresses designed to establish their credibility on international affairs. ![]()

Former Florida governor Jeb Bush, who delivered an address last Tuesday at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in California, and Florida senator Marco Rubio delivered an address to the Foreign Policy Initiative in New York. Bush and Rubio alike delivered plenty of bromides about projecting U.S. strength and toughness against the enemies of the United States, with plenty of withering attacks on the foreign policy of the Obama administration, including the likely Democratic presidential nominee, former secretary of state Hillary Clinton. But critics on both the right and the left panned the speeches as the same old neoconservative sauce poured back into a barely disguised new bottle.

From Slate‘s Fred Kaplan on the Bush speech:

His 40-minute speech, at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, was a hodgepodge of revisionist history, shallow analysis, and vague prescriptions.

From The American Conservative‘s Daniel Larison on Rubio:

Once again, Rubio fails to understand the limits of applying pressure to another state…. Rubio boasts about wanting to usher in a “new American century,” and these are the bankrupt, discredited policies he wants to use create it.

From Vox‘s Zack Beauchamp:

Jeb Bush didn’t mention his brother, George W. Bush, Tuesday night in his foreign policy speech. But he might as well have…. Jeb’s speech is a reboot of his brother’s neoconservative view of the world, albeit in a somewhat stripped-down form. He thinks American military power “won” the war in Iraq. The lesson we should learn, Bush suggests, is that a bigger US military commitment to the Middle East is the best way to solve its biggest problems.

Ultimately, these haughty foreign policy speeches have little to do with establishing a foreign policy vision. They’ve become part of the traditional bunting of a modern presidential campaign — like flag pins and campaign rallies and the increasingly customary mid-summer overseas trip in general election years (à la Barack Obama in 2008 or Mitt Romney in 2012) that, at best, amounts to a weeklong photo-op and pedantically positive news coverage. In a primary election, grand foreign policy addresses are one part presidential playacting and one part rallying the base.

* * * * *

RELATED: What would Jeb Bush’s foreign policy look like?

* * * * *

For all the posturing, these speeches will all be long outdated by the time either Bush or Rubio hopes to take office in January 2017. Despite bluster on Cuba and Iran, it will be nearly impossible for any presidential administration, Democratic or Republican, to roll back US-Cuban normalization or to shred an international agreement on Iran’s nuclear energy program agreed among European, Chinese and Russian leaders, notwithstanding Rubio’s promise last week to do precisely that.

That’s assuming Cuba and Iran will even be foreign policy priorities in a year and a half.

Any number of intervening crises could pull attention away from Cuba, Iran or even ISIS, Iraq and the Syrian civil war quagmire. Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment in Brazil. Plunging GDP contraction in China. Russian aggression against Kiev or the Baltic states. Skirmishes between Pakistan and India. A succession crisis in Oman that fuels a war on the Arabian peninsula. Another terrorist attack in the United States. Security disintegration in east Africa. A rogue nuclear bomb.

Short of truly consequential moments in U.S. foreign policy (the 2003 congressional vote on Iraq, for example), it’s relatively easy for candidates to say one thing on foreign policy, then do another. Who remembers that George W. Bush’s 2000 campaign so strongly stressed a ‘humble’ American foreign policy?

To paraphrase Mario Cuomo, one campaigns in hyperbole and governs in prose. In a campaign in which Donald Trump brags that he’ll whip foreign leaders into shape from Saudi Arabia to China to Mexico (and still wins about 25% of the GOP primary vote), there’s little harm for candidates like Bush and Rubio to throw foreign policy red meat to a hawkish Republican base. For all the tough talk, it’s really hard to imagine any mainstream Republican administration launching a fresh war in the Middle East. So while Wisconsin governor Scott Walker, another leading candidate for the Republican nomination, might engage in relatively neoconservative bluster, his chief goal is to say nothing to distinguish himself on foreign policy, other than to show he clears the bar as a potential commander-in-chief, despite his lack of international affairs experience.

Frankly, it would be far more instructive for each Republican candidate to name his or her top choice for national security adviser, secretary of state and secretary of defense. (For all the admiration among the 2016 field for the incendiary former US ambassador John Bolton, the most clearly qualified potential Republican to lead State in 2017 remains former World Bank president Robert Zoellick, and he’s a hard-nosed realist.

Bush, Rubio and every other potential president will confront the same limitations of American power in 2017 and 2018 that their predecessors faced. It’s a simple fact that the United States does not have unlimited power to bend the wills of 195 other countries around the world. It was supposed to be the non-interventionist libertarian champion, Kentucky senator Rand Paul, making these kind of lucid, should-be-obvious points in the Republican primary debate. (Even Paul is hedging his bets with uncharacteristically hawkish language, disappointing his own base.)

Despite the bellicose neoconservatism of former president George W. Bush’s first term, his second term was much more realist. On issues like unmanned drones, Guantanamo Bay and engagement in Libya, Syria and Iraq, the antiwar left has often dismayed at the Obama administration’s continuity with the Bush administration — and sometimes far from the dovish positions that characterized Obama’s ascent to the White House. Tim Mak at The Daily Beast argues that when you strip away Jeb Bush’s rhetoric, his plan for confronting ISIS — engaging moderates Sunnis, arming the Kurdish peshmerga and deploying limited US airpower — is essentially the same as the Obama administration’s current approach.

Most US administrations have steered a foreign policy course of realism (Bush’s first term is the exception, not the rule). Republicans are currently locked in a pre-primary contest that, six months away from the first votes of Iowa and New Hampshire, feels more like a reality show than an exercise of democracy. That’s more than enough reason to set aside the pronouncements of summer 2015 — they will have virtually no impact on the way a Bush or Rubio administration will actually conduct foreign policy.