Imagine a North America with three, not two, countries north of the Rio Grande — the United States, Canada and… Newfoundland.![]()

![]()

Newfoundland!? That’s right. The Canadian outpost in the north Atlantic. Imagine today a proud population of nearly 530,000, now basking in the proceeds of a thriving offshore oil market, growing interest in summer tourism and a historical reliance on fisheries.

It’s not as crazy as it sounds — and if not for the votes of 7,000 Newfoundlanders on this day in 1948, the proudly sovereign country of Newfoundland and Labrador might exist today as a strategic Atlantic hub.

With an area slightly larger than Bangladesh or Greece, and with a population similar to that of Luxembourg and larger than the populations of Iceland, Belize, Brunei or Malta, the Canadian province today has a GDP per capita of nearly $68,000, in Canadian dollars (as of 2013) — much higher than the Canadian average of nearly $54,000.

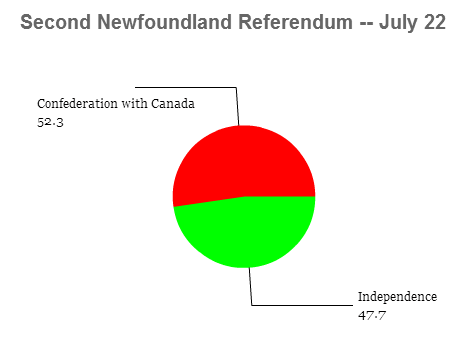

On July 22, 1948, nearly 150,000 Newfoundlanders voted in the second of two fiercely contested referenda. They decided, however narrowly, in favor of confederation with Canada. On April 1 of the following year, Newfoundland and Labrador became the 10th Canadian province. The referendum brought to an end 15 years of uncertain status — that’s because in 1934, the essentially independent ‘Dominion of Newfoundland’ reverted back to colonial status after a financial crisis left the country unable to service its debt.

Sound familiar? Relations today between Greece and the rest of the eurozone (most especially Germany) are as strained as ever. With a third bailout effectively ceding control of Greek fiscal policy from prime minister Alexis Tsipras to European authorities, Newfoundland’s example holds instructive lessons on sovereignty and debt. The referendum — and the failure of the pro-independence campaign — also provides a data point for aspiring nations like Scotland and Catalunya.

Nearly 80 years of sovereignty

Newfoundland first won self-rule in 1854, with the introduction of ‘responsible government,’ and it acquired more formal dominion status (equivalent to the dominion status Canada held) in 1907.

That independence was always somewhat constrained by Newfoundland’s economy. Stretching back to the earliest claims on the territory after the first English voyage to the New World, led by John Cabot in 1497, and throughout the tussles over its control between the English and the French in the 17th and early 18th centuries, cod fishing dominated the island’s economy. Fishermen would harvest the cod from the plentiful fish banks surrounding Newfoundland’s shores and, in the days before refrigeration, dry the cod for shipment and sale to Europe.

Demand for a protein like dried fish, however, ebbed and flowed with global economic trends, making independent Newfoundland highly dependent on foreign trade to meet its own obligations. In the 1890s, it was forced to turn for the first time to Canadian banks to extend credit and avoid a default. The experience left the Canadians and Newfoundlanders mutually suspicious, and in the early 20th century, Newfoundland’s premier Sir Robert Bond tried to negotiate a free-trade accord with the United States (an attempt thwarted in 1905 by US senator Henry Cabot Lodge, despite the support of the US president at the time, Theodore Roosevelt).

World War I was particularly harsh on Newfoundland — nearly all of the members of the Newfoundland Regiment were killed on the first day of the Battle of the Somme. Taken together, its portion of the British empire’s war debt amounted to $35 million. Still rebuilding after the loss of so many of its young, able-bodied men in Europe, Newfoundland and its export-driven economy crumbled, predictably, with the crash of 1929. By 1933, the country was unable to service its debt, which had grown to $97 million (including its war obligations). Canadian banks, also struggling during the Great Depression, had no desire to extend financial credit, and Canada’s government wasn’t willing to provide political cover to Newfoundland.

So, nearly overnight, 79 years of home rule and a tradition of national politics ended, and Newfoundland once again became a colony under direct British rule.

From dominion status to debt colony

As the Great Depression waned and World War II gradually became the more pressing matter, Newfoundland emerged as a convenient colonial holding for the British. The aviation base at Gander (established only in 1935) became a vital stopping point in the mid-Atlantic efforts of British and American air forces during the war. As you might expect, the British-dominated commission that administered Newfoundland never quite found the time to address its status during the war effort. Though the colony’s geostrategic importance crested throughout World War II, Newfoundlanders also rediscovered their love of Americans. With so many US military personnel in Newfoundland, locals developed strong ties — including a fair share of marriages. Newfoundlanders felt for the United States none of the disdain it held for Canada, stretching back to the financial crisis of the 1890s, and none of the scorn it shared for its British debtor overlords.

By the end of the war, the friendly sentiment towards the United States was so strong that Newfoundlanders talked freely about economic partnership — or even, eventually, becoming a full American state. Canada, suddenly very concerned that the Americans might scoop up much of the North Atlantic coastline, began to force the Newfoundland issue on Great Britain. The British, for their part, were already looking to liquidate their colonial holdings and, with the war now over, the Newfoundland question could no longer be further delayed.

Though there’s no clear evidence that the ultimate voting was fraudulent, authorities in Ottawa and London did their best to nudge Newfoundland toward Canadian union. Canada made clear in negotiations that it would be willing to assume much of Newfoundland’s debt; the British government made it equally clear that Newfoundland would get little in return for reverting to ‘responsible government.’

Even the nature of the two referenda also boosted confederation — when no option won a clear majority in the first vote, elites decided to hold a second vote between the top two options.

Two pivotal 1948 votes to determine Newfoundland’s future

The campaign was a vigorous one — though it was somewhat more complicated than a direct two-way fight between independence and confederation.

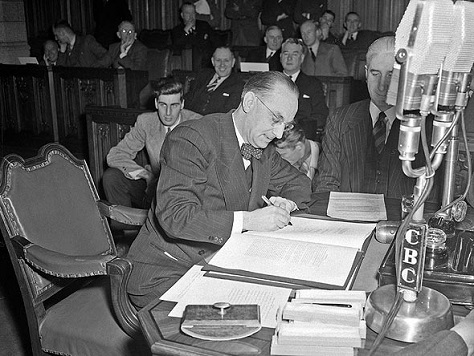

Confederation’s champion was Joey Smallwood — a Liberal radio show host who embraced Canada and who nearly single-handedly pushed the cause through the Confederation Association. The cause of merging into Canada attracted support mainly from the Protestants of rural Newfoundland and Labrador; less so from the urban business class of St. John’s. After successfully pushing confederation, Smallwood (pictured above) would become the province’s first and most long-lasting premier, serving until 1972 and shaping Newfoundland’s transition as a part of federal Canada.

Peter Cashin, a one-time Newfoundlander finance minister, was a member of the 1947 commission to London that so disappointed Newfoundland’s leaders when the UK government refused to commit to financial assistance. Disillusioned by British intentions, and rightly suspecting that the British and Canadian government were colluding to favor confederation, Cashin led the Responsible Government League throughout the referendum campaign. In a famous 1947 speech to the national convention on Newfoundland’s future, he condemned what he called:

a conspiracy to sell… this country to the Dominion of Canada. Watch in particular the attractive bait which will be held out to lure our country into the Canadian mousetrap. Listen to their flowery sales talk which will be offered to you; telling Newfoundlanders they’re a lost people….

At minimum, Cashin believed that a return to responsible government would give Newfoundland a stronger hand in any potential talks on confederation, including the terms on which Newfoundland might join Canada — with respect to debt, provincial assistance and Newfoundland’s rights vis-à-vis the national government with respect to fishing and resources.

The most beguiling option came with the Economic Union Party, the brainchild of businessman Chelsey Crosbie. Though you might not be able to tell it from the name, the ‘economic union’ meant union with the United States — not with Canada. Crosbie’s group, which became even more popular than the Responsible Government League, hoped that independence would allow closer ties with the United States. US statehood was never presented on the ballot, even though there’s a plausible case that it might have won in light of the Newfoundlandish good will to the Americans during World War II. Though US president Harry Truman never seriously considered annexation, it’s conceivable that after a decade of closer economic partnership, Newfoundland could have become the 51st American state in 1959 alongside Alaska and Hawaii.

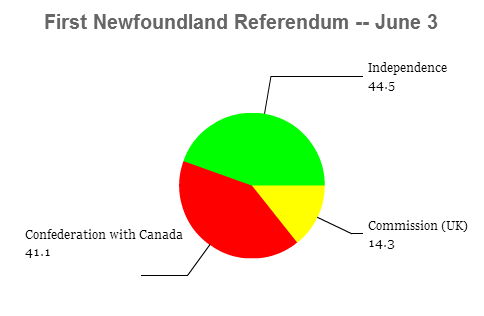

As established by the national convention (and heavily influenced by the British commission still governing Newfoundland), the first referendum on June 3 presented three choices — (i) confederation with Canada, (ii) retaining commission government (i.e., as a British colony) or (iii) a return to ‘responsible government’ (i.e., independence).

None of the options won more than 50% of the vote, though independence emerged with the largest share among 155,797, a turnout of around 88%.

With no clear mandate for confederation or for independence, Newfoundland’s government scheduled a runoff between the top two options. Smallwood, the best Newfoundland politician of his generation, rallied the rural Protestant electorate, effectively outwitting the pro-independence business class in St. John’s and throughout the more Catholic Avalon peninsula.

Despite the joint efforts of the Responsible Government League and the Economic Union Party, Smallwood simply rallied more voters in an election that registered wide swings in opinion. Nearly 78% of Labrador’s voters, for example, supported confederation, while St. John’s voted at around 68% in favor of responsible government.

By a margin of just under 7,000 votes, Newfoundlanders turned to confederation.

Perhaps the most important lesson from the Newfoundland example is that independence is a much easier cause when an overwhelming proportion of the population favors it. As in the case of Newfoundland, when a region is narrowly divided, it’s hard to achieve a convincing pro-independence majority (Quebec in 1980 and 1995, for example, and Scotland in 2014). But once the cause reached a certain tipping point, the path to independence seems clear. In Norway (1905), Iceland (1944) and South Sudan (2011), the independence option won over 99% of the vote.

Confederation with Canada and Newfoundland’s economic decline

With the 10th province’s addition, Ottawa secured a Canadian writ from Pacific coast to Atlantic coast and, more importantly, won national control over Labrador’s iron ore and Newfoundland’s Grand Banks. In exchange, Canada assumed Newfoundland’s debt obligations and committed to additional family relief in the form of ‘baby bonuses’ to the province.

But Newfoundland stagnated throughout the second half of the 20th century, with its natural resources diverted to national use. Under the control of the federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Newfoundland’s fishing stocks suffered from overfishing as Ottawa awarded concessions to foreign fishing interests. In 1992, the government reversed course by imposing a moratorium on cod fishing, which essentially forced the collapse of Newfoundland’s fishing industry. That, however, may have been too late, and cod stocks still haven’t recovered. The moratorium instantly eliminated nearly 40,000 jobs for Newfoundlanders, causing an unemployment and economic crisis that marked the province’s post-confederation nadir.

When you go to Newfoundland today, the most striking thing is perhaps the lack of rail infrastructure (or even road infrastructure) that connects so much of mainland Canada. It’s almost certain that the young, newly independent country would have struggled, given London’s indications that it would receive no debt relief upon a return to ‘responsible government.’ But taking advantage of Gander’s notoriety, Newfoundland was well on its way to becoming a transit hub for North America, rather than the Atlantic backwater it became as a Canadian province.

Between 2003 and 2010, under the premiership of Danny Williams, a member of the province’s center-right Progressive Conservatives, Newfoundland seemed to reclaim some of its national swagger. Williams waged a fervent fight against Canadian prime minister Paul Martin to allow the province to keep more of the revenue developed from its growing offshore oil production — a move that made Williams the most popular premier since Smallwood. At one point in the showdown with the federal government, Williams ordered the Canadian flag removed from the province’s official buildings.

Williams was so popular that, for the past five years, his legacy has floated a series of underwhelming Tory premiers. The current incumbent, Paul Davis, will make his case in the province’s next election on November 30, where the party trails both the center-left Liberals and the progressive New Democrats.

The showdown with Ottawa coincided with the sense that Newfoundland’s newly exploited oil wealth might have supported the economy of an independent nation.

It’s not uncommon to see, throughout St. John’s, the unique tricolor — a pink, white and green standard that has recently become a symbol of Newfoundlandish nationalism, though it was historically a flag representing the island’s Irish Catholic heritage.

On the 67th anniversary of the pivotal vote that made Newfoundland a Canadian province, however, its cautionary tale still holds lessons about debt, sovereignty and international relations.

One thought on “The lessons of Newfoundland’s 1948 referendum”