Imagine it is May 2016, and Scottish voters are going to the polls to select the members of its regional parliament at Holyrood.![]()

![]()

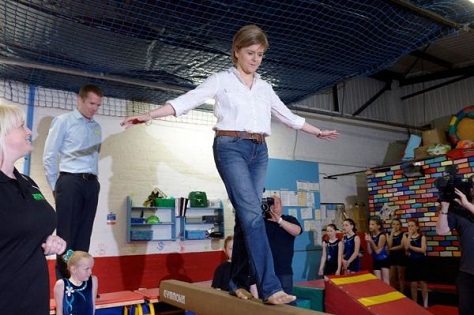

You’re Scottish first minister Nicola Sturgeon, and you’re asking voters to deliver a third consecutive term to the ruling Scottish National Party (SNP), the pro-independence, social democratic party that’s controlled Scottish government since 2007.

* * * * *

RELATED: Scotland could easily hold the balance of power in Britain

* * * * *

Which scenario would you prefer?

In the first scenario, Sturgeon and the Scottish nationalists can stir up votes by promising to protect Scottish values from a second-term Conservative government that’s propped up by the socially conservative Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) of Northern Ireland or the eurosceptic, right-wing United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP). It’s a government that doesn’t include a single Scottish MP, and it is dead-set on renegotiating the terms of the United Kingdom’s membership in the European Union and then putting it up for a referendum of British voters in 2017. Poisoning English-Scottish relations, prime minister David Cameron won reelection in May 2015, in part, by scaring English voters that a Labour government supported with SNP votes would be chaotic, treacherous and inauthentic. All the while, the Cameron-led government slow-rolled the ‘devolution max‘ reforms promised so stridently in the days leading up to the 2014 independence referendum in Scotland, even as it is slashes spending on education and social welfare programs. Meanwhile, the British economy is growing only sluggishly, translating into no discernible boom for the average Scotsman. You could fairly well guess that Scottish voters would be in a mood to deliver their support to the SNP as a counterweight to the Tories.

In the second scenario, the SNP is waging a defensive campaign, and both Sturgeon and former first minister Alex Salmond are both on the backfoot after endorsing Labour prime minister Ed Miliband’s government after the 2015 elections. Despite receiving no formal invitation to join a governing coalition alongside Labour, depriving the SNP of any real power in government ministries, the SNP nonetheless has been forced to stand by every unpopular decision of the Miliband government. Meanwhile, the British economy is growing only sluggishly, translating into no discernible boom for the average Scotsman. But the 2015 vote showed Scottish voters, however, that in the right scenario, a party devoted to Scottish sovereignty could conceivably have a real say in policymaking in Westminster. Moreover, it’s clear that Miliband has no intention of agreeing to a new referendum on Scottish independence anytime this decade — or even allowing much of a debate over relocating the Trident nuclear deterrent from the Firth of Clyde. Though former SNP supporters are in no mood to return to supporting the Scottish Labour Party, they’re instead turning to alternatives. Those include the Liberal Democrats (once again in opposition), the Scottish Green Party (led by the familiar and increasingly popular Patrick Harvie), the Scottish Conservatives (led by the openly lesbian Ruth Davidson, hardly your typical Tory) and even UKIP. Critics note truthfully that, even as the SNP demands even greater local automony, it’s failed to use the power that’s already been devolved to it to vary income tax rates from those in England. You could fairly well guess that Scottish voters would be in a mood to punish the SNP for its inefficacy.

For the first time in British history, Scottish nationalists could find themselves after May 7 holding the balance of power in the House of Commons, and Sturgeon could easily cast the most important vote in deciding the United Kingdom’s next prime minister. The latest YouGov / Sunday Times poll from April 29 to May 1 gives the SNP a wide lead of 49% to just 26% for Scottish Labour, 15% for the Scottish Conservatives and 5% to the Scottish Lib Dems.

With great power comes great responsibility, and if the SNP allows Miliband to become prime minister, it will hold responsibility for the ensuing government’s decisions, popular or not. So it’s not entirely clear that the landslide that polls show will come in favor of the SNP on May 7 in the British general election will necessarily boost the party’s short-term goals in holding onto power in Scotland’s parliament or its long-term goals of winning Scottish independence.