Twenty-three years ago, Neil Kinnock was expected to defeat a tired Conservative Party, reeling after three full terms in government that barely seemed capable of limping into its fourth.![]()

Instead, Tory prime minister John Major won the 1992 election, against all expectations, thwarting Kinnock’s second chance at restoring Labour to government. Kinnock stepped aside as leader, and his role in Labour’s revitalization was quickly marginalized with the election of Tony Blair as Labour leader in 1994 and Blair’s landslide ‘New Labour’ victories in 1997, 2001 and 2005.

But when Blair’s successor, Gordon Brown, lost the 2010 election, the ‘New Labour’ label had become tired and somewhat toxic. Moderate voters blamed Brown for the excesses of the financial crisis and, more fundamentally, opposed Blair’s involvement in the US invasion of Iraq and the growth of what critics called a widening police state across Great Britain. Moreover, progressives and the labour union activists that had historically been at the heart of Labour wanted a new approach that recovered some of the social democratic populism with which Labour was once synonymous.

It was no shock, then, when Neil Kinnock emerged as a leading adviser to the lesser-known Ed Miliband in his attempt to win the Labour leadership crown in 2010.

* * * * *

RELATED: Would David Miliband be doing better than Ed?

RELATED: Blair role virtually non-existent as UK campaign heats up

* * * * *

Miliband, of course, famously succeeded, defeating his own brother, former foreign minister David Miliband, on the strength of his support from labour unions and activist groups, which represented one of three equal constituencies in the Labour leadership contest (Ed lost the other two among Westminster MPs and among regular Labour party members).

From the start of the Ed Miliband era, then, Kinnock has been a close informal adviser and mentor to the young Labour leader, marking something of a rehabilitation for a former Labour leader who himself came just shy of becoming prime minister. Kinnock’s daughter-in-law is Danish Social Democratic Party leader Helle Thorning-Schmidt, since October 2011 the prime minister of Denmark. Her husband, Stephen Kinnock, is widely favored to win election to the House of Commons this week as a Labour MP for the Welsh constituency of Aberavon.

As the election approaches this week, Kinnock has been as much of a hindrance as a help to Miliband — just as Kinnock did, Miliband struggles to project a convincing image that he will be an effective prime minister. The comparison has not been to Miliband’s advantage. Over the weekend, Miliband unveiled an eight-foot stone monolith carved with key Labour pledges. The stunt was met with wide derision from social media and elsewhere — one Telegraph columnist called it Miliband’s ‘Kinnock moment.’

Alan Johnson, the 64-year-old shadow home secretary is far more likely to play the initial role of Miliband’s senior statesman. An affable figure who befriended both the Blair and Brown camps, Johnson swatted down rumors late last year that the party should ditch Miliband in favor of Johnson himself.

Nevertheless, if Miliband goes on to become prime minister, Kinnock is well placed to serve in an official capacity in a Labour government, and it’s no exaggeration to say that Kinnock is more influential in today’s Labour Party than Tony Blair — a result that would have been unfathomable five or ten years ago.

At age 71, Kinnock is still young enough to hold office, and he’s the rarest of Labour senior statesmen with no ties to the Blair/Brown era. He has the credibility of a man who stood as opposition leader longer than anyone else in the Thatcher era. It’s not unimaginable that Miliband would entrust to Kinnock an important policy project, much the same way that Conservative prime minister David Cameron tasked former chancellor Kenneth Clarke with justice and sentencing reform and former party leader Iain Duncan Smith with pensions reform.

Ironically for someone with so much experience at the pinnacle of British politics, Kinnock never got the chance to serve as a government minister at all. As a Welshman, however, Kinnock might be deployed as Labour’s liaison to the Scottish Nationalist Party (SNP), which is expected to hold the balance of power in the House of Commons if it wins, as projected, many of Scotland’s 59 seats.

After his precipitous fall from Labour’s leadership in the aftermath of the 1992 election, Kinnock took on several roles as an elder statesman. Her served for nearly a decade in Brussels as the United Kingdom’s representative to the European Commission, overseeing the transport portfolio from 1995 to 1999 and the administrative reform portfolio from 1999 to 2004. He’s held several roles since then and, in January 2005, he was appointed to the House of Lords as a life peer.

The Welsh-born elder Kinnock began his parliamentary career in 1970. Interestingly enough, when the Labour government of the day proposed devolution to Wales, the unionist Kinnock was just one of a handful of MPs to oppose it, and Welsh voters subsequently rejected devolution in a 1979 referendum, putting the issue to rest until Blair’s government took up devolution successfully in the late 1990s. An avowed socialist and the shadow education secretary in the early days of Labour’s opposition to Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government, Kinnock easily won the Labour leadership in 1983 and attempted a softer version of what Blair would more convincingly accomplish in the 1990s — move the party closer to the center-left.

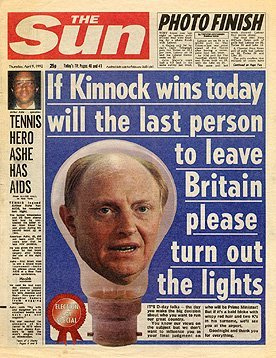

Despite a scare to Thatcher’s Tories in the 1987 election, with polls in the final week of the campaign showing Kinnock’s Labour essentially tied, the Conservatives easily won a third term in power. Despite a leadership challenge from Tony Benn, Kinnock retained the Labour leadership and, five years later, Kinnock was widely expected to boot the Tories in the 1992 election, after the Conservatives replaced Thatcher with John Major, a move that ultimately helped the Tories eke out a narrow 21-seat majority. On the election’s eve, The Sun published an infamous anti-Kinnock cover. It was so effective that the tabloid later claimed credit for engineering a last-minute Conservative victory.