He may be one of Australia’s most conservative prime ministers in recent history, but Tony Abbott isn’t above using government as a nudge to coerce better public policy outcomes.![]()

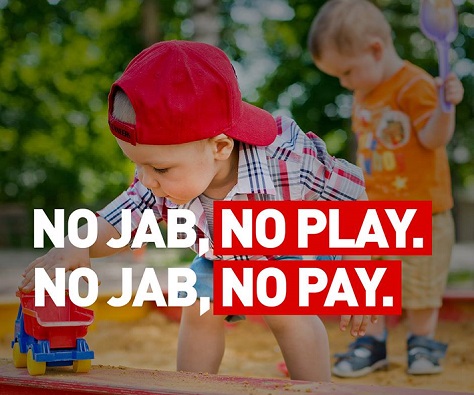

Earlier this week, Abbott announced that Australia’s national government is serious about compelling parents to vaccinate their children from diseases, such as measles, mumps, rubella and whooping cough, that were largely eradicated in the post-vaccination era, and that are now returning as larger numbers of parents refuse to vaccinate their children out of fears of autism or other untoward health effects. Doctors overwhelmingly argue that there’s no link between vaccination and autism or other severe side effects.

The anti-vaccination movement has become an increasing problem throughout the world for many reasons, including both pious Muslims in northern Nigeria (who have resisted polio vaccinations) and health-conscious leftists in California (with fears over autism). The Abbott government’s step is one of the most aggressive steps that any government in the world has taken to coerce parents to accept vaccination.

Starting in January 2016, the government will no longer recognize an exemption for ‘conscientious objectors,’ which currently allows nearly 40,000 Australians to refuse vaccination for their children. That, in turn, has boosted the number of incidents of childhood diseases that had largely disappeared (and not only among children). The change means that Australian parents stand to lose funding of up to A$2100 (equivalent to US$1600) per child in tax credits and up to A$15,000 (equivalent to US$11,400) in additional government funding, including rebates for child care, if they continue to refuse to vaccinate.

With enough participation in a vaccination program, not every person needs to be vaccinated, because of the so-called ‘herd immunity’ that comes when a high percentage of a population has been protected. It provided protect to those who can’t tolerate the vaccine, including very young children or the immune-compromised. But it also creates a ‘free-rider’ problem, whereby any given individual has an incentive to opt out of vaccination due to the fear, real or imagined, of any risk that might come with receiving a particular vaccine.

The leader of Australia’s Labor Party, Bill Shorten, approves the measure, which will almost certainly secure parliamentary approval for the change.

The closest equivalent in the United States would be akin to revoking the child tax credit (worth around $1,000 per child) and other social welfare assistance from parents who refuse to vaccinate their children. Though much Australian government assistance is means-tested, there’s a stronger government role in providing child care benefits to parents in Australia than in the United States, so the reach of Abbott’s ‘carrot/stick’ approach goes deeper. Moreover, many American anti-vaxxers are relatively well-off, so the economic impact would be especially minor for them.

Some Australian experts argue that the policy change won’t persuade the most fervent opponents of vaccination, and the continued observation of a religious exemption means that the strong-willed could still find a way to circumvent the government’s efforts — a hard-core anti-vaxxer might simply be able to join the Christian Scientist church.

If Abbott’s push is successful, it might open the way for a more aggressive approach by US state governments or even the US federal government, especially if Democratic US president Barack Obama (or his successor) can win bipartisan support from a chiefly Republican US Congress. Though California governor Jerry Brown signed a law in 2011 that attempted to make it tougher to opt out of vaccination, there’s no evidence that the law has had much effect, leading to calls from state lawmakers for more stringent legislation. Most vaccination laws are adopted at the state level in the United States, and the laws vary widely — Mississippi’s, for example, is among the most stringent because it’s one of two states (the other is West Virginia) that doesn’t allow for religious exemptions.

Proponents of tougher state legislation in the United States will be watching Australia closely in 2016 and thereafter to see whether the Abbott government’s policy change turns out to be as effective as hoped.