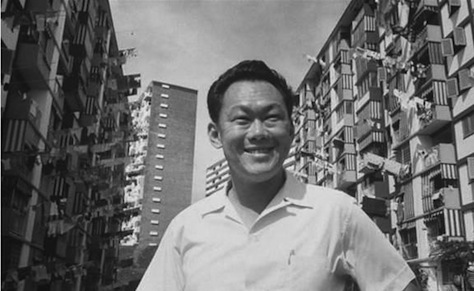

The father of modern Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, died Monday at the age of 91.![]()

Obituaries, prepared long ago by news outlets for Lee’s passing, will note that Lee presided over Singapore’s economic transformation from an uncertain city on the Malaysian peninsula into one of the world’s wealthiest countries on the strength of a strong central government, a thriving market economy, strict social conformity and a bit of soft authoritarianism.

The deal that Lee offered Singapore in 1965, for the next 25 years of his premiership and the ensuing 25 years of his ‘retirement’ that saw the rise of his son, Lee Hsien Loong, as prime minister in 2004, is simple: the promise of sustained economic growth and a robust social safety net at the expense of real democracy, liberal freedoms of speech and expression and a strong free press. It also entailed a nanny state, enforced by cultural norms as much as by government diktat, that deployed housing quotas to integrate Indian and Malay minorities among the larger ethnic Chinese population, forced retirement savings, compulsory two-year military service for Singaporean men, and strict rules that imposed the death penalty on drug offenses and that nudged (or pushed) Singaporeans to be more polite, learn English, stop chewing gum and self-censor any dissent of Lee and his ruling People’s Action Party (PAP).

As many of Lee’s obituaries will proclaim, it’s a deal that appeared to work — Singapore today has a (nominal) GDP per capita of over US$55,000, slightly higher than the United States, and political and economic experts alike routinely use words like ‘miracle’ to describe Singapore’s rise to become one of the wealthiest, most developed countries in the world.

Central to the Singapore story was Lee himself — indeed, the first in his series of memoirs is entitled simply ‘The Singapore Story.’

But how central was Lee to the modern creation of Singapore? He’s become a beloved figure, especially in the United States in the business-school-case-study-set kind of way. It’s impossible to separate Lee’s life and his role in Singapore’s rise, but it’s not impossible to argue that Lee was shrewd, competent and… very lucky.

Founded by Sir Thomas Raffles in 1819 as a trading post for the British empire in Asia, modern Singapore’s foundations lie in its role as a major colonial trading hub. Despite its importance for over a century, the British surrendered Singapore to the Japanese in 1942, beginning an ugly three-year period of occupation, a prologue to the end of British colonial power.

Lee became chief minister of Singapore in 1959, in the period of self-rule when Singapore was still a British colony. He rose to power after a landslide election victory of the People’s Action Party, then a scrappy opposition with sympathies to Singapore’s communists. He initially won the PAP’s leadership because he had fewer ties to Singapore’s communists and thanks to his grasp of the English language.

Ironically, both of his predecessors as chief minister, David Marshall and Lim Yew Hock, had engaged in crackdowns against the left. (Lim, who was appointed Malaysia’s high commissioner to Australia in 1963, recalled after a mysterious nine-day disappearance in 1966, ultimately left public life, converted to Islam and moved to Jeddah in Saudi Arabia, where he died in 1984). Lee ended the siege on Singapore’s communists, initially to the dismay of the British and other Western countries at a time when Cold War tensions were running high. He wasted no time, however, neutralizing the old leadership of his party. China’s leader, Mao Zedong, had four years earlier already dismissed Lee, who studied in England, as ‘like a banana –yellow of skin, white underneath.’

But Lee’s initial priority as Singapore’s leader wasn’t to transform the city-state into a regional powerhouse. It was to engineer a merger with what would become the federation of Malaysia in 1963. It went poorly. With the Malaysian government intent on favoring ethnic Malays over ethnic minorities, Singapore was the scene of deadly race riots in 1964. Mistrustful of the Chinese-majority city and, perhaps, foreseeing the outsized economic role that it would one day hold, Malaysia’s parliament voted in 1965 to expel Singapore from the federation, leaving an uncharacteristically teary-eyed Lee struggling with his country’s future:

Lee’s first instincts would have been disastrous for Singapore — a Chinese city tethered to a Malay-majority country that, even today, is still struggling to achieve the kind of economic liftoff that Singapore, Hong Kong, South Korea and other countries in Asia enjoy today. Though Lee reluctantly took up the project of an independent Singapore, he quickly did so with same fervor as the Malaysia merger. He quickly sought UN recognition for Singapore, and he built a security infrastructure that today costs more than the military spending of Indonesia, the world’s fourth-most populous country. But it’s worth repeating — Lee’s first vision for Singapore would have left it much less wealthy than it is today.

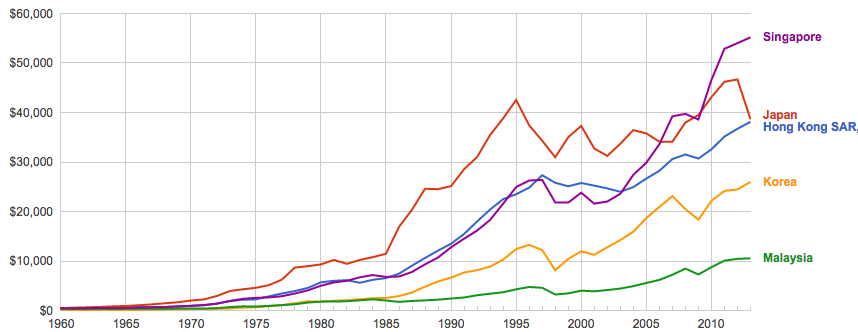

Moreover, the comparison to Hong Kong is especially revealing. Both city-states would become hubs for commerce-minded Chinese entrepreneurs outside the Chinese mainland, with plenty of foreign capital to encourage them. It’s remarkable the extent to which the GDP growth in Singapore and Hong Kong correlate from 1965 until 1990, when Lee stepped down as prime minister:

The obvious inference is that, though British colonial rule of Hong Kong through 1997 may not have been democratic, liberal freedoms didn’t especially hinder the same kind of economic ‘miracle’ there. Even in South Korea, where Park Chung-hee’s authoritarian rule from 1961 to 1979 coincided with its emergence as an economic power, growth didn’t slow with the gradual introduction of democracy. Lost in the Lee hagiography is the fact that he enjoyed, in Hon Sui Sen and Richard Hu, two widely capable finance ministers, who steered a consistent economic policy between 1970 and 2001. Is it so hard to believe that Singapore would have thrived even under a less visionary leader?

The trajectory of Singapore’s GDP growth in the last decade, however, in which its economy far outpaced not only Hong Kong, but Malaysia (a country of almost 30 million people), suggests that it may be in the midst of a real estate bubble fueled by the same froth that floated emerging markets between 2008 and 2012. The end of China’s historic double-digit annual growth, the sharp rise in the value of the US dollar and the inevitable gravity of property bubbles all point to trouble ahead for Singapore — we may look back to the 2010 completion of the opulent Marina Bay Sands, an instantly iconic hotel, as an early sign of a hard landing for Singapore’s boom.

Singapore, as much today as in 1965, has no natural resources, so its economy remains highly dependent on exports and subject to global swings. Although nearly 13% of the country’s 5.4 million population are millionaires, it suffers from some of the most extreme income inequality in the world. Low birthrates and an aversion to importing foreign labor could hamper future economic growth, and Alwyn Young’s iconic 1992 paper on Hong Kong and Singapore argued that the latter’s productivity growth was much less impressive than the former’s.

Singaporeans will remember Lee Kuan Yew today, upon his passing, on largely positive terms, and his place in history is secure as the founding father of modern Singapore and, in many ways, modern Asia. His legacy to world politics may even be his role translating the cultural divide between China and the United States, more then any lessons from the bespoke ‘Singapore model.’ But today’s Singapore was not Lee’s original vision for Singapore; his path for Singapore’s growth wasn’t necessarily the only path to prosperity and there is no guarantee that Singapore will continue to achieve the same levels of miraculous growth.

After Singapore mourns Lee, and as it turns to its future (with elections in 2017 poised as a genuine opportunity for the opposition Worker’s Party), its citizens may find the moment ripe to reevaluate the deal that Lee struck a half-century ago with respect to the balance of economic opportunity and individual freedoms.

One thought on “Is Lee Kuan Yew’s role in Singapore’s rise overrated?”