A poll late last week confirmed that, if survey trends hold, it will be very difficult for the Labour Party to form a new government without the support of the pro-independence Scottish National Party (SNP) after the United Kingdom’s May 7 general elections.![]()

![]()

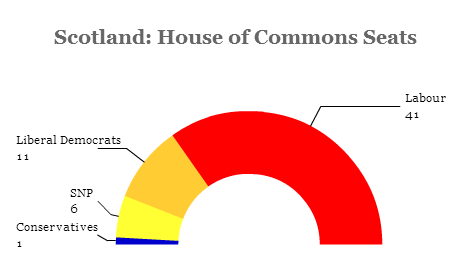

Presumably, that makes Labour leader Ed Miliband’s declaration this week ruling out any coalition with the SNP somewhat awkward with the reality that the SNP may win between 40 and 50 of Scotland’s 59 seats in the House of Commons, many of which are currently held by Labour MPs and which for years were reliable seats on the Labour backbenches — so reliable, in fact, that none of those 59 constituencies changed parties between the 2005 and 2010 general elections.

No longer.

With polls showing that Labour’s narrow lead against the governing Conservative Party has vanished, the SNP earthquake means that Labour is unlikely to form a government without at least some form of SNP support and, notably, Miliband didn’t rule out an informal arrangement whereby the SNP supports a Labour minority government. Nevertheless, just six months after Scottish voters narrowly rejected independence, they are now set to determine the balance of power throughout the entire United Kingdom.

* * * * *

RELATED: Scottish referendum results — winners and losers

* * * * *

Post-referendum, Scottish voters are now flocking to the SNP not only in regional politics (the SNP controls a majority government in the Scottish parliament) but in national politics as well. With the SNP winning nearly half of the Scottish vote and with a lead of around 20% against Labour, it could turn Scotland almost universally yellow (the SNP’s color), wiping out Labour’s Scottish heartland and depriving the Liberal Democrats of many of their 11 seats as well, nearly 20% of the LibDem MPs in total.

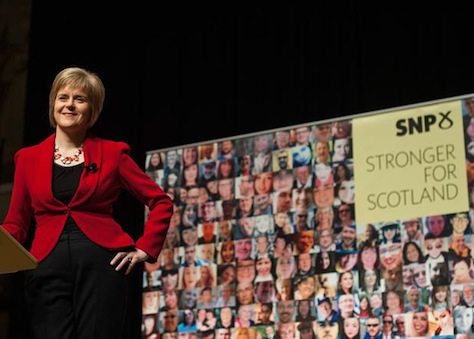

It’s not entirely surprising. Scottish voters are keen to hold Westminster accountable for promises of ‘devolution max,’ a set of promises made desperately by Labour and Conservative leaders alike in the last days of the referendum. When the ‘Yes’ campaign lost the referendum, Alex Salmond stepped down both as SNP leader and as Scotland’s first minister. Though he remains a relatively beloved figure in Scotland, his replacement, Nicola Sturgeon (pictured above) is even more popular, especially among young voters, evincing a more progressive edge than Salmond’s hard-edged leftism forged in the divisive politics of the 1970s.

Notably, something very similar happened in Québec in the period surrounding its last independence referendum in 1995. In the 1993 federal election the sovereigntist Bloc québécois emerged as the winner of 54 of the province’s 75 ridings. For a lot of reasons, having to do with the collapse of the center-right Progressive Conservative Party and the rise of the Western-based Reform Party, the Bloc won enough seats to become Canada’s official opposition. Though it won just 44 seats in the 1997 federal election, the Bloc won more votes than any other party in Québec during Canada’s federal elections until 2011.

The latest YouGov/Times survey of Scotland voters from mid-March claims that 85% of all pro-independence voters will back the SNP in the general election, including many prior Labour voters, including 81% of those who votes ‘Yes’ in 2014 but supported Labour in 2010. Labour is currently winning just 48% of its 2010 voter base, and the Liberal Democrats are retaining just 14% of theirs. (The Conservatives, with low support in Scotland since the days of Margaret Thatcher, win just 18% of the vote in total). Remarkably, the incredible swing to the SNP would deprive Charles Kennedy, the former Liberal Democrat, of his Highlands seat, and Labour would lose even those seats currently held by former prime minister Gordon Brown and former chancellor Alistair Darling, both of whom held prominent roles in the multi-party ‘Better Together’ campaign that opposed Scottish independence.

Even though the slump in global oil prices have subdued the immediate economic case for Scottish independence, more voters support an independent Scotland today than they did last September.

Though Brown, in particular, is widely credited with persuading Scottish voters to vote to stay in the British union, many more Scottish voters now disregard Labour as a wan ‘Red Tory’ version of the Conservatives. Though Scottish voters traditionally lean to the left of the English electoral, in general, Sturgeon and the SNP promote a deeply social democratic agenda that increasingly mimics the social welfare agenda of the Nordic countries and not the centrist, pro-business agenda of Blairite Labour.

If the Scottish Labour Party, under the leadership of Jim Murphy, can’t turn the party’s fortunes around in the next 50 days or so, the SNP might easily control a large enough bloc of seats in the House of Commons to deny either the Tories or Labour a majority, with or without the support of the Liberal Democrats that now serve as the junior partner in prime minister David Cameron’s government.

Sturgeon has encouraged English voters to support ‘progressive’ Labour candidate or Green Party candidates, and she has publicly called for a progressive majority in the next Parliament to deny Cameron the premiership.

The politics of a formal Labour-SNP coalition, however, are fraught with difficulties. Cameron’s Tories, including the right-wing English media, have hammered Miliband over his refusal, until earlier this week, to rule out a formal coalition with the SNP. With Westminster holding very little power over Scotland’s ‘domestic’ policy, many English voters already resent the fact that Scottish MPs continue to vote fully on matters that now effect England — one of the odd effects of devolution that created Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish parliaments with no English equivalent. It’s a resentment that Cameron has been willing to exploit:

David Cameron said it was “despicable” that Mr Miliband had not ruled out a post-election deal with the SNP. “Not ruling out a deal, or a pact, or support from the Scottish National Party means that the Labour Party is effectively saying, ‘We’re trying to ride to power on the back of a party that wants to break up our country,'” he told Buzzfeed.

Despite Sturgeon’s enthusiasm, the SNP isn’t necessarily as sanguine about joining government, either, which could tether it to a Labour Party that’s still very much more centrist than the SNP and that is now very unpopular in Scotland, in no small part over Blair’s decision to join the US military effort in Iraq last decade. It might also undermine the case for independence by showing that Scottish nationalists can play a constructive role in guiding British government and policy.

Ironically, it’s the first-past-the-post voting system, which has kept the representation of third parties in Parliament relatively low over the years, that could drive the SNP’s electoral bounty. Indeed, the SNP’s rise coincides with a similar boost in the fortunes of two smaller parties — the eurosceptic United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) and the leftist British Green Party. Nevertheless, because the United Kingdom uses single-member districts (and not proportional representation), the relatively greater number of votes nationwide for UKIP and the Greens will be disbursed across many, many more constituencies, making it very difficult for either party to win more than a handful of seats (though they could easily swing the vote from Labour to Conservative or vice versa). With the SNP vote concentrated in just 59 districts, it give the SNP a chance of winning far more Scottish seats in the House of Commons than they would otherwise be entitled under a proportional representation system.