Guest post by Kevin Buettner

Born of a catastrophic civil war, the world’s newest country, South Sudan, is now still mired in a civil war of its very own.![]()

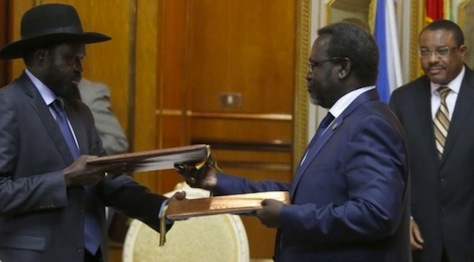

Within the last 15 months, more than 1.5 million South Sudanese were displaced, and thousands more were killed in what has become an increasingly ethnically charged conflict. After a week of face-to-face meetings between South Sudanese president Salva Kiir and the leader of the armed rebels, former vice president Riek Machar, the two produced no meaningful framework. The failure to create an attainable and lasting roadmap for peace, a prerequisite for a transitional government by July 9, 2015, is the latest stumble in the troubling history of the young nation.

Initially, the February agreement to strike a deal creating an interim government for 30 months met with optimism. But the March 5 deadline for a more detailed power-sharing agreement passed without a final framework, leaving the peace talks in limbo — but planned elections nevertheless scuttled.

As part of the initial agreement, the government agreed to delay presidential elections last month until 2017, a troubling sign for any pretense of South Sudanese democracy. In a one-sided move, the ruling Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) offered an amendment to the transitional constitution of the South Sudan. Onyoti Adigo, the leader of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement for Democratic Change (SPLM-DC), argued that the opposition didn’t have a chance to weigh in on the bill’s negotiation, and he worried that the SPLM will simply repeat the process again and again to retain power indefinitely, though he’s previously argued that any truly valid elections must follow the peace process. Adigo’s party, the second-largest in the national legislative assembly, holds just four seats in the 170-member body, versus 160 for the governing SPLM.

* * * * *

RELATED: Who would win a South Sudanese civil war? Khartoum.

* * * * *

The decision to delay the 2015 elections resulted directly from the ongoing peace negotiations between Kiir’s Juba-based government and the militant rebels that it’s been battling since late 2013. With time running out to implement a peace proposal before scheduled summer elections, which might well have resulted in an elected government that could scrap any peace deal altogether, Kiir’s administration instead offered to extend the mandate of the current government to demonstrate to the militants the willingness to adopt reforms hammered out through the negotiation process.

Those negotiations, however, may end up threatening the legitimacy of the South Sudanese government itself. Without support from more powerful regional capitals like Addis Ababa and Nairobi, the current government will have a doubly difficult task to convince international arbitrators to support any resulting proposals. Many of South Sudan’s neighboring nations in the region have distanced themselves from Juba at a time when South Sudan needed to build crucial ties with east African governments. Instead, they are increasingly aligned with the SPLM-IO (SPLM in Opposition), Machar’s party — or disillusioned with both sides altogether.

The international community, which fought so hard to facilitate South Sudan’s sovereignty, is now showing signs of impatience at a country that’s been stuck in a costly civil war for nearly half of its existence. Both enthusiastic proponents of independence, including the United States, and skeptics like the People’s Republic of China, which remains far closer to the northern Republic of the Sudan (which scheduled its own election for July) and which invests heavily in South Sudan’s oil fields, have an interest in stability. So far, that’s been elusive. For example, while the country inaugurated in 2012 a road between Juba and the Ugandan border, it remains too unsafe to travel, stifling any chance of South Sudanese regional trade.

The United Nations Security Council voted on Tuesday to impose sanctions on any faction in South Sudan’s civil war, including the Juba-based government, that it believes is blocking the development or implementation of a lasting peace agreement in the country. Though there’s a genuine ethnic component to the war, whereby the Dinka group (backing Kiir) opposes the Nuer group (backing Machar), many international observers worry that the civil war is more political in nature, a power struggle between Kiir and Machar that dates to before 2011 and the decades that spanned the South Sudanese fight for independence. That’s one reason why even the African Union is considering a recommendation to bar both Kiir and Machar from any transitional government.

The UN sanctions would initially consist of travel bans and asset freezes. For now, the UN resolution omitted an arms embargo, lamented by numerous international organizations such as Human Rights Watch and UNICEF, in large part due to the high numbers of reported child soldiers being recruited by government militias, the conflict’s high casualty rate and threats of further economic catastrophe, including food shortages.

Even though outsiders are beginning to think about a solution that involves none of the key players, the current peace process’s impasse follows from disputes over the role of the rebels in any transitional government. Kiir has rejected a proposal for a unity government made up of equal numbers of current government officials and Machar-backed supporters who, for good measure, have also demanded part of the wealth generated by the vast petroleum reserves located within stretches of the country’s north, along with payment of debts incurred by Machar’s rebels in the past two years.

Without agreements on these issues, there is little hope the conflict in South Sudan will ever be resolved, which means more bloodshed and no chance for the democratic process to develop. It remains to be seen, however, if the international community has the attention and the patience to demand the kind of game-changing dynamism to jolt South Sudan out of its growing pains.

Kevin Buettner is a graduate student from The Ohio State University studying City and Regional Planning with an interest in international development.