It’s a slow election year in Germany, so there will be few tests at the state level for chancellor Angela Merkel, her center-left ‘grand coalition’ partners or any of the various challengers to Merkel’s hold on German centrism.![]()

![]()

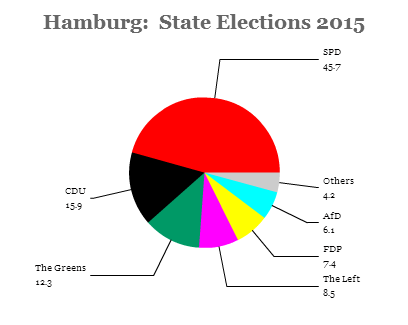

That makes the results from Sunday’s election in Hamburg, a city-state in the German north, perhaps more important than they otherwise would be, and it’s not great news for Merkel’s center-right Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands (CDU, Christian Democratic Union), which won just one-third as much support as its center-left rival (and partner in federal government), the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD, Social Democratic Party).

* * * * *

RELATED: Thuringia and Brandenburg election results —

Left, AfD on the rise

* * * * *

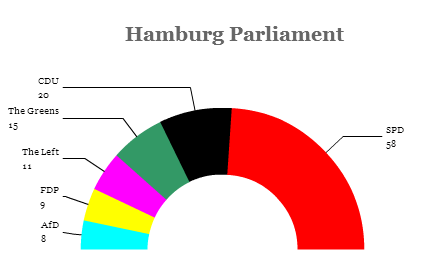

The CDU and the SPD continue to be the largest of Germany’s political parties and, notwithstanding the fact that they have joined together in the second ‘grand coalition’ in 10 years, the two parties fight fiercely at the state level and will contest Germany’s next national elections later this decade. Nevertheless, it wasn’t unexpected that the SPD, under the leadership of Hamburg first mayor Olaf Scholz (pictured above), would easily win the election. Though the SPD lost four seats, enough to deprive it of its absolute majority, Scholz will almost certainly form the next government, likely with Die Grünen (the Greens).

The troubling aspect for the CDU isn’t that it did so poorly in Hamburg, which has traditionally leaned toward the SPD, but that it seems to be losing voters to more right-wing alternatives, including the mildly eurosceptic Alternative für Deutschland (AfD, Alternative for Germany), which actively advocates that Greece and other countries leave the eurozone. It’s the four state where the AfD has now surpassed the minimal threshold to win seats in the state parliament/assembly.

The CDU’s former junior coalition partner, the Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP, Free Democratic Party), actually gained some support against its 2011 election results, also likely at the CDU’s expense. The FDP, which in September 2013 fell below the 5% threshhold for representation in the Budenstag, the lower house of Germany’s parliament for the first time in the postwar era, won its first seats in any state-level assembly for the first time since 2013. It now holds seats in just six state parliaments, though its success in Hamburg will give it some hope that its brand of liberalism, both social and economic, is not quite extinct as a political brand in Germany.

Merkel and the CDU shouldn’t necessarily be too troubled by the result, but it does indicate that there are limits to Merkel’s shape-shifting ability to cover the entirety of the mainstream political spectrum. As the differences between the CDU and the SPD have blurred in the past decade, it’s become easier for groups like the AfD on the right and Die Linke (Left Party), on the far left, to siphon voters from the two major parties. In Thuringia last autumn, for example, the Left performed so well in elections that it now leads its first state government as the senior governing partner (alongside the SPD and the Greens) under minister-president Bodo Ramelow.

Even more troubling is the rise of a new anti-Islam movement in Germany, Patriotische Europäer gegen die Islamisierung des Abendlandes (PEGIDA, Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the West), founded last autumn. Its influence is limited in a country that has for decades embraced diversity and multiculturalism, especially after photos surfaced of its founder Lutz Bachmann posing as Adolf Hitler, despite the group’s initial claim that it wasn’t, in fact, xenophobic. But its presence indicates a growing presence on the German right of the kind of anti-immigration views that have become increasingly common from France to Sweden to the United Kingdom to Denmark. Though Merkel has co-opted much of the space that the SPD once occupied and embodied a consensus-driven government, it may be opening a new space for a more strident conservatism in the political and economic engine of the European Union.

Hamburg, like Bremen and Berlin, is a ‘city-state’ and, just as Bremen, traces its status as one of the chief Hanseatic trading cities in prior centuries. With 1.75 million people, Hamburg is the second-largest city in Germany and a financial and cultural hub for northern Germany, in particular. Though the SDP has traditionally held an edge in Hamburg, the CDU thrived politically in the 2000s, when Ole von Beust served as the city’s quite popular first mayor.

Bremen, another northern city-state with just 548,000 people, will vote on May 10 and, again, the SPD is widely expected to emerge as the leading party and, as in Hamburg, likely to remain in coalition with the Greens. Also in Hamburg, the AfD and the FDP both have a chance at winning seats, in each case pulling votes from different elements of the CDU coalition.