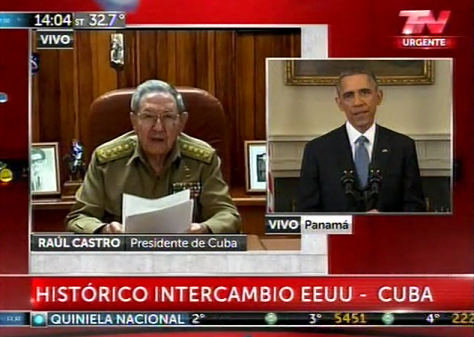

In one of the most significant foreign policy steps of his administration, US president Barack Obama announced widespread changes in the US-Cuba relationship on Wednesday, including the reestablishment of the first US embassy in Cuba in over a half-century and relaxed rules for US commerce, travel and engagement with the island nation of 11.25 million.![]()

![]()

It’s a historic play, and it yanks one of the biggest straw-men arguments out from under Cuba’s aging Castro regime. But the announcement brings with it more questions than answers for both the United States and Cuba, as the two countries begin negotiating a new chapter in a troubled relationship, even long before the 1959 Cuban Revolution, the failed 1961 Bay of Pigs / Playa Girón invasion and the 1962 missile crisis. Cuban disenchantment with the United States stretches back to at least the 1903 Platt Amendment that established unequal relations through much of the first half of the 20th century, culminating in the brutal regime of US ally Fulgencio Batista, overthrown in Castro’s 1959 revolution. Obama shrewedly signalled in his statement Wednesday that he understands the broader arc of Cuban-American relations by quoting José Martí, a founding father of Cuban independence who was killed in 1895 by Spanish forces.

* * * * *

RELATED: Did Hillary Clinton just lose Florida

in the November 2016 presidential election?

RELATED: A public interest theory of the

continued US embargo on Cuba

* * * * *

As the two countries, which represent two very different brands of political thought within the Western hemisphere, begin to set aside their differences, here are six questions that are as unclear today as they were last week.

1. How will the Obama administration establish an embassy and appoint an ambassador to Cuba without Republican support?

If you think ordinary confirmation hearings will be contentious after Republicans take control of the US Senate in January, imagine how difficult it will be for Obama to appoint an acceptable ambassador to Havana for the first time in six decades, to say nothing of the difficulty of restoring an embassy in a world where plenty of Republicans, including conservative stalwarts (and potential 2016 presidential candidates) like Ted Cruz of Texas and Marco Rubio of Florida try to halt funding to any Cuba-related activities. It won’t be an easy fight, least of all because the embargo remains codified in law, as strengthened by the 1996 Helms-Burton Act. The Obama bet is that the momentum of closer ties with Cuba will ultimately be strong enough to force Congress to act. Maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but soon. He obviously believes that the politics (including the presidential politics involving Florida’s 29 electoral votes) have changed. By what degree, though?

It was certainly a way of reminding former US secretary of state Hillary Clinton, who is the anti-embargo frontrunner for the Democratic Party’s 2016 presidential nomination, that Obama still has some mojo in the final two years of his administration, not to mention (pro-embargo) former Florida governor Jeb Bush, who took a step closer Monday to seeking the 2016 Republican nomination.

One early contender will be Jeffrey DeLaurentis, who is now the chief of mission in the U.S. interest section in Havana and will shortly be promoted to charge d’affaires. Another choice is former New Mexico governor Bill Richardson, himself a Mexican American, and a former Clinton cabinet official, Democratic presidential candidate, former ambassador to the United Nations and something of a long-time unofficial envoy to North Korea. Another more bipartisan pick might be a Republican-leaning Cuban American businessman, such as former Bush commerce secretary Carlos Gutierrez.

2. Is Guantánamo Bay’s closure part of this deal?

It was odd when, earlier this month, José Mujica, the outgoing president of Uruguay, mentioned Cuba-US relations when he agreed to resettle three prisoners from the US prison facility at Guantánamo Bay. The presence of a US military installation on the island of Cuba has been a slap at Cuban sovereignty for the entire duration of the Castro era. Noting Obama’s pledge during the 2008 campaign to close the prison facility at Guantánamo and, amid speculation, that he finally will in the final quarter of his administration, it would be shocking if repatriating Guantánamo to Cuba wasn’t at least part of the conversations between US and Cuban officials. That’s not to say that Obama will do so, but the opening to Cuba does seem to place more pressure on at least closing the prison. A corollary: I know Pope Francis is receiving much of the credit as the key intermediary that helped close this deal, but I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that Mujica played an incredibly important role.

3. Will Miami-Havana (or DC-Havana or NYC-Havana) become a more popular flight like Taipei-Beijing?

So with more relaxations on general licenses for US travelers, including journalists and other professionals, how are all of these folks going to get to Cuba? American Airlines flies multiple runs between Miami and Havana daily, but it’s clear that the US airline industry (and, perhaps, Air Cubana) will have to ramp up their cross-country services. Thinking about this aspect of Cuba liberalization reminds me of the growing links between Taiwan and the mainland People’s Republic of China. Though Taiwan’s ruling party is suffering these days for moving too fast on strengthening ties with Beijing, it should be pretty clear that the PRC and Taiwan are growing closer. That may not be great for Taiwanese sovereignty, but it’s still good news for avoiding World War III. Direct flights between Taipei and Beijing played a huge role in that. It’s not hard to imagine, by the end of 2015, direct flights from New York City or Washington to Havana, and that will create even more momentum for ending the statutory embargo.

4. Who wanted the Obama executive action more — Cuba or the United States?

I’m not sure how many people actually watched both Obama’s announcement and the short speech that Castro delivered simultaneously. But the more muscular of the two was clearly Obama’s speech. Castro’s speech was relatively tame by comparison. This is about as critical as Castro was:

This in no way means that the heart of the matter has been solved. The economic, commercial, and financial blockade, which causes enormous human and economic damages to our country, must cease…. While acknowledging our profound differences, particularly on issues related to national sovereignty, democracy, human rights and foreign policy, I reaffirm our willingness to dialogue on all these issues.

That comes as something of a surprise, because of the few remaining rationales for the ruling Partido Comunista de Cuba (

5. How many US officials have a sophisticated understanding of Miguel Díaz-Canel?

Like it or not, the Castros are in their final days, even if the Castroist regime is not. Fidel Castro, at age 88, transferred his powers to brother Raúl in 2006 and is now retired. Raúl, now age 83, was elected president in his own right in 2008 and reelected last year, but indicated he won’t seek a new term in 2018. His most likely successor seems to be Miguel Díaz-Canel (pictured above), who became first vice president in March 2013.

Raúl Castro’s administration has been marked by significant privatization and liberalization of the Cuban economy. Though the state sector still reigns supreme in Cuba, there’s at least something of a legal private market emerging today, and Raúl has accelerated that. Díaz-Canel is something of a cipher within Cuban circles, so how many US officials know anything about Díaz-Canel? He’s typically described as a conservative behind-the-scenes power within the Castro regime. If that’s true, the real window for influencing Cuba toward smarter economic policy and political freedom is now, not in a decade’s time under a Díaz-Canel regime struggling to perpetuate Castroism without the Castros. You could easily imagine Díaz-Canel or any Castro successor, for that matter, leaning on anti-Americanism to sustain populist political support.

6. Does Cuba really need the United States so much?

Though Cuba had a rough time in the 1990s with the collapse of its patron, the Soviet Union, China has largely replaced Russia as the chief investment source for Cuba these days. Though the imagine of Havana as ‘trapped in the 1950s’ remains, that’s not quite the full reality, though it’s helpful in drawing tourists — from Europe, from Canada, from the rest of Latin America. Chinese president Xi Jinping flew to Havana earlier this year, where he met former president Fidel Castro (pictured above). It’s probably much more significant than, say, any benefits that Cuba receives from Venezuela, where Cuba is widely rumored to control the country’s intelligence service. It’s certainly no secret that the late Hugo Chávez leaned heavily upon the Castros for political support and guidance, and it’s true that in the boom days, Cuba did well from chavismo. But that’s not enough to float the entire Cuban economy.

The conventional wisdom is that upon the end of the embargo, US-based capital will flood Cuba and transform it from picturesque decay into a world of JPMorgan Chases, Starbucks, Apples and McDonalds. But it will not be as easy as that, especially given the existing China-Cuba investment ties. Nor will Cuba’s capital markets necessarily open to the degree to provide US investors with the kind of assurances they would need — an ‘open’ Cuba might still look more like Argentina or Venezuela than, say, Peru or Chile or even Brazil.

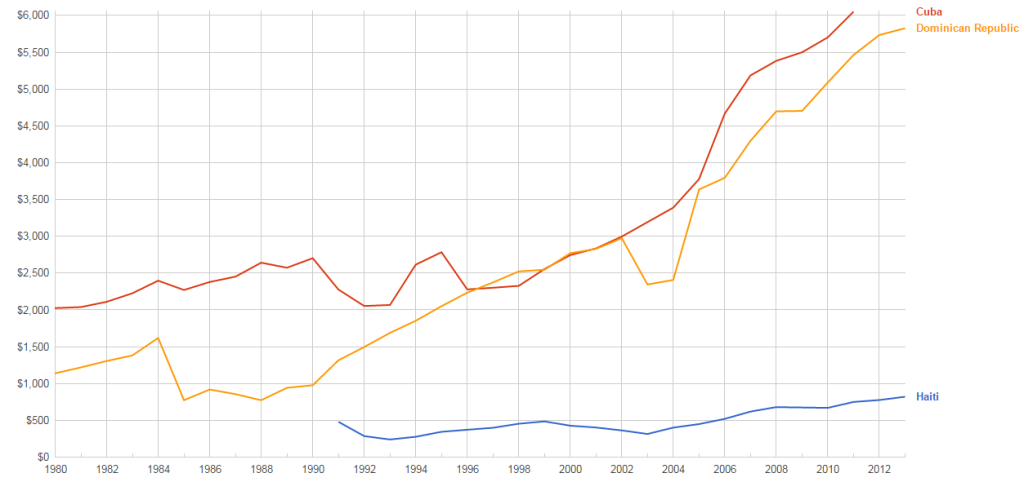

What’s most fascinating is that Cuba has consistently outperformed the other two most populous Caribbean countries, Haiti and the Dominican Republic, neither of which has been shut out from US and global investment for the past 55 years — in spite of all that, Cuba’s GDP per capita (red in the chart below) slightly outpaces that of the Dominican Republic (yellow), both of which massively outpace Haiti (blue):

It’s easy to think of Cuba as falling behind, and there’s no doubt that Cuba has massively underperformed over the past 54 years, in no small part self-inflicted from stifled freedoms and socialist policies that retarded growth and prosperity. It’s true that the embargo’s end would boost investment (especially among the Cuban American community that has a head start in building capital networks to Cuban businesses), but it’s not necessarily going to transform Cuba into a capitalist outpost overnight — and given the deep-seated distaste for heavy-handed US policy toward Cuba between 1899 and 1959, that’s probably a good thing.

One thought on “Six key questions about the landmark Cuba deal”