Just days after former prime minister Valdis Dombrovskis was nominated as the European Commission’s vice president for the euro and social dialogue, his successor back home in Latvia is fighting to keep Dombrovskis’s party in power after five tumultuous years.![]()

Laimdota Straujuma, a former civil servant and, until her election as prime minister on January 22, Latvia’s agriculture minister, will attempt to win another mandate on October 4 for the broad center-right coalition government that, in the form of many different parties and combinations, has governed Latvia since its independence in 1993. Dombrovskis’s newly formed party, Vienotība (Unity), the fusion of an alliance of several center-right liberal parties, won Latvia’s October 2010 elections and, though it finished in third place in the most recent September 2011 snap elections, it continues to govern in alliance with three other center-right and populist parties.

If Straujuma (pictured above) is successful, she should send flowers to the Kremlin, because Russia’s newly aggressive tone with respect to its ‘near abroad’ has become a leading factor during the campaign.

When Dombrovskis became prime minister in 2009 amid the global financial crisis, Latvia was facing its worst economic turmoil since the post-Soviet adjustment of the early 1990s. Dombrovskis prevented a devaluation of the lats currency, salvaging Latvian hopes to enter the eurozone (it did in January 2014).

But Dombrovskis’s orthodox economic policy forced budget cuts and a steep internal devaluation and boosted Latvia’s unemployment rate in 2009 to what was then a EU-wide high of 20%, which today rests just above 11%. Though growth has bounced back, Dombrovskis resigned last December after a freak accident in a suburb of Riga, the Latvian capital, when a supermarket roof collapsed and killed 54 people.

In a normal election, with a weary Latvian electorate, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to expect its center-left party to take advantage of years of austerity to form what would be Latvia’s first truly center-left government.

* * * * *

RELATED: Despite risks, Latvia (and all the Baltic states)

still wants to join the eurozone

RELATED: Who is Laimdota Straujuma?

Latvia’s likely first female prime minister

* * * * *

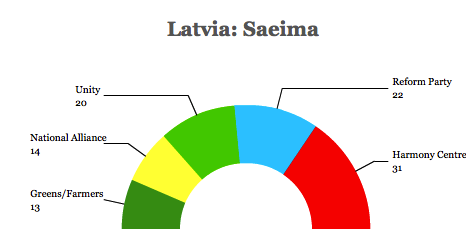

What’s more, Latvia’s center-left party, Sociāldemokrātiskā Partija ‘Saskaņa’ (Social Democratic Party “Harmony,” which previously contested Latvian elections as the wider ‘Harmony Centre’ alliance), was on something on an upswing, winning the largest number of seats in the 2011 elections (31) in the Saeima, the 100-member, unicameral Latvian parliament, and it made even stronger breakthroughs in the 2013 local elections, when Harmony took control of the Riga city council.

But what held Harmony Centre and now, the ‘Harmony’/Social Democratic Party back was its historical role as a party supported mostly by ethnic Russians and Russian speakers. Though Latvia has the largest ethnic Russian population of the three Baltic states (around 26.9%), that’s not a large enough support base to build a majoritarian government.

So in 2011, though Harmony Centre won more seats than any other party, the rest of the Saema, a combination of populist, agrarian, nationalist, liberal and center-right parties, lined up in coalition with Dombrovskis instead. It’s not just that ethnic Latvians were alarmed at a Russian-interest party controlling the Latvian government, but the party’s sympathies toward Moscow and its ongoing cooperation with United Russia (Еди́ная Росси́я), the party of Russian president Vladimir Putin.

Photo credit to LETA, Ieva Lūka.

Photo credit to LETA, Ieva Lūka.

Moreover, Nils Ušakovs, the longtime leader of both the Harmony Centre alliance and the Social Democratic Party, the latter which now just refers to itself as ‘Harmony,’ and Riga’s mayor since 2009, has done little to assuage fears among ethnic Latvians, who worry that his loyalties lie more with Moscow than Brussels — or even Latvia. Time after time, Ušakovs has denounced US and European sanctions against Russia and defended Russia’s annexation of Crimea earlier this year. Though Ušakovs can reasonably compete in Riga, where 40% of the population is Russian, all signs indicate that his Social Democratic Party / ‘Harmony’ is doing worse in an era when Putin is taking a much more aggressive stand with respect to the ‘near-abroad.’

Even though Ušakovs has tried to emphasize the ‘social democratic’ nature of his party, he hasn’t done much to even try to assuage fears that he’s a Kremlin puppet. That strategy may help maximize his support among one-quarter to one-third of the Latvian electorate, but it will also foreclose any possibility of a Harmony-led government so long as Harmony is more the ‘Russian’ party than Latvia’s ‘center-left’ party.

It’s not surprising that in the most recent May elections for the European parliament, Unity won 46.2% of the vote and four out of eight MEPs. The Latvian nationalist National Alliance (NA, Nacionālā apvienība) finished in second place with 14.3%, pushing Harmony to just 13% and one seat.

That success comes after Unity’s major center-right rival, the Reformu partija (Reform Party), which was created only in 2011 by former Latvian president Valdis Zatlers, imploded. The net result is that Unity is now a truly united coalition of like-minded liberals.

The biggest problem for Unity is that its top two politicians have left national politics for EU politics — Dombrovskis as the Commission’s vice president for the euro and former defense minister Artis Pabriks was elected in May as a member of the European parliament. Though Straujuma was a tough negotiator with respect to the EU Common Agricultural Policy and a strong advocate for Latvian farmers, she lacks the kind of political talent that Dombrovskis used to remain prime minister for five turbulent years.

Polling is limited, but a recent Norstat survey showed that Unity and Harmony were both tied at 15.5%, with 30% of the electorate undecided. A populist agrarian party, the Zaļo un Zemnieku savienība (ZZS, Union of Greens and Farmers), wins 7.5% and the National Alliance wins 7%.

Photo credit to Nora Krevneva/AFI.

Photo credit to Nora Krevneva/AFI.

The Union of Greens and Farmers is a conservative group that appeals mostly to pensioners and rural Latvians. Its prime ministerial candidate is Aivars Lembergs (pictured above), the oligarchic businessman and corruption-dogged mayor of Ventspils, whose backing for the party has sometimes kept it out of the current coalition. The ZZS rejoined the government in January when Straujuma became prime minister, and it might hold the balance in a hung parliament. But Lembergs, who has been charged in graft cases and who has voiced skepticism with both the European Union and Latvia’s NATO membership, hardly represents the kind of liberalism that Zatlers, Dombrovskis and Straujuma would otherwise like to project.

Another new party, No Sirds Latvijai (‘Latvia from the Heart’), a centrist effort founded by former state auditor Inguna Sudraba, whose popularity comes from her efforts to root out corruption. The Norstat polls gives her party 5.6% support, just enough to surpass the 5% hurdle to win representation in the Saeima. A late swing, however, isn’t out the question, given Latvian wariness with the center-right’s austerity policies, the center-left’s Moscow connection and the corruption that Lembergs and others personify. That, in turn, could make her party a key player in post-election coalition negotiations that could put Sudraba in a position to become a key minister in the next government.

Meanwhile, Harmony could face at least minor competition from Latvijas Krievu savienība (Latvian Russian Union), which is even more nakedly pro-Putin than Harmony and which still advocates making Russian an official state language, a policy that Latvians overwhelming rejected in a 2012 national referendum.