Voters go to the polls in Scandinavia’s largest country on September 14, and if he can hold onto the lead that his party has enjoyed for over a year, former labor leader Stefan Löfven (pictured above) will become Sweden’s next prime minister. ![]()

That’s slightly surprising because most Swedes don’t necessarily give center-right prime minister Frederik Reinfeldt poor marks. In two terms, Reinfeldt has earned praise, domestically and abroad, for his government’s economic stewardship, bringing Sweden out of the 2008-09 financial crisis with some of the strongest growth in the European Union. In that time, Reinfeldt has reduced the size of Sweden’s public sector, while nevertheless retaining the character of his country’s renowned social welfare state.

Reinfeldt’s governments amassed an impressive series of legislative accomplishments over the past eight years. Under his watch, Sweden privatized several public interests, including the maker of Absolut vodka, and otherwise deregulated the pharmaceutical, telecommunications and energy industries. Reinfeldt introduced the earned income tax credit to reduce taxes on the poorest Swedes while instituting a series of tax cuts, including the abolition of the wealth tax in 2007 and a reduction in the VAT rate on restaurants from 25% to 12%. His government also passed a law to permit same-sex marriage in 2009 with wide support from the opposition.

In his government’s second term, Reinfeldt avoided the recession that otherwise afflicted much of the rest of the eurozone. Though Reinfeldt and his finance minister, Anders Borg (pictured above, right, with Reinfeldt, left), have resorted to deficit spending to boost Sweden’s economy, their budget deficits haven’t fallen much below 1% of GDP. That’s a much better fiscal record than the average eurozone member, and it’s kept Swedish public debt at the relatively low level of around 40% of Swedish GDP.

It’s arguable that by reforming, privatizing or abolishing the least efficient areas of the Swedish public sector, Reinfeldt’s governments updated for the 21st century the existing welfare state that the long-dominant Sveriges socialdemokratiska arbetareparti (Swedish Social Democratic Party) built in the 20th century.

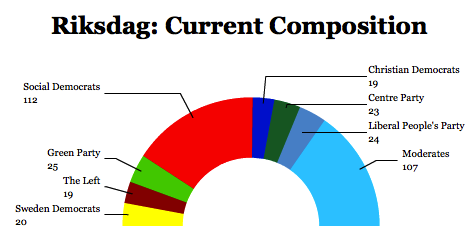

Nonetheless, on September 14, Swedes will elect all 349 members of the country’s unicameral parliament, the Riksdag, and surveys indicate that voters feel like it’s time for a left turn in Sweden’s governance.

Though 310 members of the Riksdag are elected through fixed constituency seats, another 39 seats are awarded to establish proportional representation at the national level with a 4% minimum threshold.

Though Reinfeldt came to prominence two decades ago as something of a flamethrower in protest of the Swedish welfare state, he remade the Moderata samlingspartiet (Moderate Party) into a truly moderate party upon assuming its leadership in 2003, not unlike the way that Norway’s prime minister Erna Solberg transformed her country’s Conservative Party. Reinfeldt won power three years later, in coalition with three other center-right parties, governing in a majority coalition in his first term and a minority coalition in his second.

The minority status of Reinfeldt’s current government has mostly to do with the rise of the far-right, anti-immigrant Sverigedemokraterna (Sweden Democrats), which won its first Riksdag seats in 2010 after winning nearly 6% of the vote, though the four main center-right parties have consistently refused to work with the Sweden Democrats over the past four years. Reinfeldt has instead pursued a broadly pro-immigration policy, often with the support of the center-left opposition.

Despite the party’s controversial fascist roots, its young leader Jimmie Åkesson (pictured above) has, tried to moderate the party’s image since assuming the leadership nine years ago. Polls show that the Sweden Democrats, however, are set to improve in this September’s election, when it could win between 8% and 12%.

If the Sweden Democrats do as well as expected, it could complicate the ability of either the center-left or the center-right to form a majority government. If the race tightens over the next month, and the Social Democrats can’t clearly form a government coalition, they could be forced to rely on far-leftist votes. Alternatively, a hung parliament could even give Reinfeldt and his four-party Alliansen an outside chance to form another minority government.

In 2006, Reinfeldt benefitted from the sense that Swedes had grown tired of the decade-long government of former prime minister Göran Persson and the century-long dominance of the Social Democrats, who have won the greatest vote share in every general election since 1914, before the era of universal suffrage in Sweden.

Even in 2010, when the Social Democrats won a 30.7% share of the vote, its lowest since World War I, the party still managed to outpace the Moderates, which won just 30.1%.

In that 2010 election, Reinfeldt and his government benefitted from the post-crisis economic recovery, when Sweden bounced back with more resilience than the rest of Europe, perhaps in part due to its own economic restructuring following a financial crisis in the 1990s. But the Social Democrats also suffered under the weak leadership of Mona Sahlin, who led the previous campaign effort. Voters also seemed wary of the ‘Red-Green’ coalition that would have brought not only the center-left Miljöpartiet (Green Party) into a Social Democratic coalition government, but also the socialist Vänsterpartiet (Left Party).

Two elections and three leaders after it lost power in 2006, the Social Democrats are now favored to return to government under the understated leadership of Stefan Löfven, the former head of Sweden’s largest metalworkers union, IF Metall.

This time around, Löfven isn’t running as part of a coalition, and he’s staying far away from the Left Party, though it’s widely expected that the Social Democrats, leading the polls, could form a government coalition with the Greens, who are winning so much support that they edged out the Moderate Party into second place in the May 25 European parliamentary elections.

More importantly, Löfven and his economic spokesperson, Magdalena Andersson, an economist and the former director of the Swedish Tax Agency, have made some headway on economic matters. among voters. Though Sweden is set to estimated to grow by more than 2% this year, unemployment remains stubbornly high at around 7.8%. The unemployment rate, though lower than the EU average, has lingered higher than expected, given Swedish growth. By contrast, Sweden’s unemployment is much higher than US unemployment, despite Sweden’s higher GDP growth.

Moreover, the Swedish central bank’s decision to hike interest rates in 2010 and 2011 now seems premature, given that Sweden this year is flirting with deflation.

The wide lead that the Swedish left enjoys has given Löfven and Andersson (pictured above), who is widely tipped to become the next finance minister, more confidence in advancing a relatively aggressive agenda that includes higher taxes, greater social spending and a regulatory crackdown on Sweden’s private equity industry, especially with respect to investments in the health care industry.

The Social Democrats have promised to raise taxes, notably on Swedish banks, to pay for additional social spending while eliminating the budget deficit. In particular, Löfven has earmarked more than one-half of the revenue from the banking tax hike for raising the salaries of public schoolteachers. The Greens, meanwhile, are posturing even farther to the left, opposing a long-delayed byway that would ring the Swedish capital of Stockholm and waxing about the benefits of a ‘no-growth’ economy.

Despite the left’s lead, Reinfeldt’s enduring popularity means that the race could tighten, and there are signs that it may already be doing so as more Swedes return from summer holidays to focus on the election. Moreover, Sweden’s top industrialist Jacob Wallenberg has warned that the Social Democrats could create instability and dissuade entrepreneurship.

While the rise of the Sweden Democrats makes forecasting the next government difficult, there’s a chance that another new party, the leftist Feministiskt initiativ (Feminist Initiative), which won 5.3% in the May elections and a seat in the European Parliament, could eke out enough votes to win seats in the Riksdag as well, though the most recent polls show their support slipping.

Reinfeldt’s Moderates wield, by far, the most support within the center-right Alliance, which also includes the liberal Folkpartiet liberalerna (Liberal People’s Party), which draws much of its support from affluent, urban voters; the Centerpartiet (Centre Party), a traditionally Nordic agrarian party with a historical focus on rural and green issues that has become increasingly libertarian under its new leader Annie Lööf; and the Kristdemokraterna (Christian Democrats), currently the smallest of the four Alliance parties. Though the Centre Party and the Christian Democrats appeared in danger of falling below the 4% threshold to enter the Riksdag, recent polls show that they have rebounded somewhat.