Over the weekend, US president Barack Obama gave a wide-ranging interview on foreign policy with New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman. ![]()

But it’s the interview that The Atlantic‘s Jeffrey Goldberg conducted with former US secretary of state Hillary Rodham Clinton that’s garnered much more attention. With Clinton leading polls for both the Democratic presidential nomination and general election in 2016, her interview was widely viewed as creating space between her own views on US foreign policy and those of the current president, who defeated her in 2008 for the Democratic nomination before appointing her as the top US diplomat in the first term of his presidential administration.

The most controversial comment seems to be Clinton’s criticism that the Obama administration’s mantra of ‘don’t do stupid shit‘ isn’t what Clinton calls an ‘organizing principle’ for the foreign policy of any country, let alone a country as important as the United States.

The headline in the The New York Times? ‘Attacking Obama policy, Hillary Clinton exposes different world views.’

Chris Cillizza at The Washington Post endeavored to explain ‘What Hillary Clinton was doing by slamming President Obama’s foreign policy.’

The Clinton ‘slam,’ though, is somewhat overrated. She admits in virtually the same breath that she believes Obama is thoughtful and incredibly smart, adding that ‘don’t do stupid stuff’ is more of a political message than Obama’s worldview. For the record, Clinton claims that her own organizing principles are ‘peace, progress and prosperity,’ which might be even more maddeningly vague than ‘don’t do stupid stuff.’ After all, who’s against peace, progress or prosperity? Even if ‘don’t do stupid shit’ is political shorthand, and even if you don’t believe that the Obama administration’s foreign policy has been particularly successful, it’s political shorthand that represents a sophisticated worldview about the respective strengths and limits of US foreign policy.

In any event, there’s an awful lot to unpack from the Clinton interview, both on the surface and from reading between the lines. You should read the whole thing, but in the meanwhile, here are six things that struck me from the interview about Clinton and what her presidential administration might mean for US foreign policy.

1. Yes, she’s running for president.

Goldberg makes it clear in his introduction to the interview, but it’s obvious for all to see that Clinton is running for president in 2016, and she drops a clear hint when she talks about her own ‘old-fashioned’ views on foreign affairs:

Goldberg makes it clear in his introduction to the interview, but it’s obvious for all to see that Clinton is running for president in 2016, and she drops a clear hint when she talks about her own ‘old-fashioned’ views on foreign affairs:

JG: I think that defeating fascism and communism is a pretty big deal.

HRC: That’s how I feel! Maybe this is old-fashioned. Okay, I feel that this might be an old-fashioned idea—but I’m about to find out, in more ways than one.

As if the recent book tour weren’t indication enough — a now well-worn stop on the pre-primary campaign trail — it’s pretty clear that Clinton is ready to make this race. She’s not even trying to be coy anymore.

It also sure seems like Clinton isn’t even going to try to run as the candidate of new ideas, at least not in foreign policy. She’s doubling down on the concept that she’ll be the most experienced potential president in the field — the same argument she made in 2008, the ‘3 a.m. phone call‘ argument. It’s not a strategy without risk for Clinton who, at age 69, will be the same age that Ronald Reagan was when he took office in 1981. Experienced though she may be, and as masterfully as she can speak to events such as the fall of Egyptian president Mohammed Morsi or the similarities between Islamic democracy today and European Christian democracy a century ago, her strategy risks tying her to the past, not to the ideas of the future.

Notably, think about all those issues that Clinton doesn’t even touch over the course of the conversation: neither the Transatlantic Trade Investment Partnership nor the Trans Pacific Partnership, neither greater coordination with Canada on energy independence nor greater cooperation with countries like India and China to reduce carbon emissions. She doesn’t discuss Africa, she doesn’t discuss Latin America, she barely discusses China, apart from a vague aside about shipping lanes in the South China Sea. This is the future of foreign policy, not just balance-of-power politics in Israel and Iran. The risk is that another candidate, either Republican or Democrat, could emphasize those issues and paint Clinton, who spent nearly half of the interview discussing the Middle East, as a candidate with a 20th century mindset.

2. Of course she’s distancing herself from

the Obama doctrine on foreign policy.

No one comes to American presidential politics with more baggage than the Clintons. The former first lady will, fairly or unfairly, face the brunt of attacks dating to her husband’s administration two decades ago, including her health care reform debacle, Whitewater and other scandals and the Monica Lewinsky affair. She’ll be forced to defend an eight-year record as a US senator from New York, including her ill-fated vote in 2002 authorizing force in Iraq. She’ll also be forced to defend against the barrage of complaints from her own time at Foggy Bottom, including the cringe-worthy Russia ‘reset’ photo op (pictured above with Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov) and the security failures at the US consulate in Benghazi that left four Americans dead.

The last thing that Clinton wants is to be saddled in 2016 with an unpopular Obama administration’s second-term policy decisions. Fairly or unfairly, there’s a general sense that Obama’s first-term foreign policy moments (e.g., killing Osama bin Laden) were much more successful than the second-term moments (e.g., indecision over Syria’s civil war, Russian aggression in Ukraine, ISIS’s destabilization in Iraq). That’s probably more hyperbole than fact, because it’s hard to measure the repercussions of policy decisions in neat, four-year increments.

But it’s understandable why Clinton wants to put some distance between herself and the current administration, it’s almost certainly smart politics, and Obama administration officials probably understand that, to some degree, that distance is a necessary step in order for the Democrats to hold the White House for a third consecutive term.

3. Clinton is triangulating her way between Bush and Obama.

Possibly the most devastating moments of the interview come when Clinton contrasts the Bush and Obama presidencies in a way that paints Obama nearly as extreme as Bush. Though it strikes me as somewhat unfair on the policy substance, it’s incredibly shrewd politics. Early in the interview, Goldberg sets up the contrast of ‘Bush overreach / Obama underreach’ for Clinton, but she doesn’t take the bait — at least not initially:

JG: Is there a chance that President Obama overlearned the lessons of the previous administration? In other words, if the story of the Bush administration is one of overreach, is the story of the Obama administration one of underreach?

HRC: You know, I don’t think you can draw that conclusion. It’s a very key question. How do you calibrate, that’s the key issue. I think we have learned a lot during this period, but then how to apply it going forward will still take a lot of calibration and balancing. But you know, we helped overthrow [Libyan leader Muammar] Qaddafi.

Nevertheless, Clinton returns to this concept at least twice later in the interview. Triangulation was one of the best tricks in the Bill Clinton playbook and here, Hillary Clinton seems to triangulate the ‘Clinton way’ squarely between Bush-era overreach and Obama-era underreach. Here’s what she has to say about the challenges of doing nothing versus ‘doing something’ in Syria:

HRC: I think part of the challenge is that our government too often has a tendency to swing between these extremes. The pendulum swings back and then the pendulum swings the other way. What I’m arguing for is to take a hard look at what tools we have. Are they sufficient for the complex situations we’re going to face, or not? And what can we do to have better tools? I do think that is an important debate.

She comes back to the same notion very soon thereafter:

HRC: Well, that’s because most Americans think of engagement and go immediately to military engagement. That’s why I use the phrase “smart power.” I did it deliberately because I thought we had to have another way of talking about American engagement, other than unilateralism and the so-called boots on the ground.

You know, when you’re down on yourself, and when you are hunkering down and pulling back, you’re not going to make any better decisions than when you were aggressively, belligerently putting yourself forward. One issue is that we don’t even tell our own story very well these days.

4. She’s very possibly more to the right on Israel

than even the Bush administration.

You won’t find much sympathy for the Palestinians in Clinton’s remarks, but the level of stridency with which Clinton blames Hamas, which controls the Gaza Strip, and excuses Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu (pictured above with Clinton) for the current military campaign and resulting civilian deaths in Gaza is particularly striking, especially after all the tension that’s characterized relations between the Obama administration and the Netanyahu government:

HRC: So what I tell people is, yeah, if I were the prime minister of Israel, you’re damn right I would expect to have control over security [on the West Bank], because even if I’m dealing with Abbas, who is 79 years old, and other members of Fatah, who are enjoying a better lifestyle and making money on all kinds of things, that does not protect Israel from the influx of Hamas or cross-border attacks from anywhere else. With Syria and Iraq, it is all one big threat. So Netanyahu could not do this in good conscience…. Dealing with Bibi is not easy, so people get frustrated and they lose sight of what we’re trying to achieve here.

Though you can easily call the Bush administration’s ‘roadmap’ approach to the Israeli-Palestinian negotiations half-hearted, Bush was nonetheless the first US president to endorse a national state for Palestine. Bush also spoke out against the security fence along the West Bank that Israel began building over a decade ago under the late prime minister Ariel Sharon.

Clinton has always been a strong supporter of Israel. That may have to do with the fact that she had to run for election in a state with a population that’s four times more Jewish (6%) than the national US population (around 1.5%). It’s becoming harder to believe that Netanyahu will still be prime minister by the time of the next US presidential inauguration, but it’s not hard to imagine Clinton building a stronger relationship with Israeli leadership, even if it veers further to the right under economy minister Naftali Bennett or foreign minister Avigdor Lieberman.

Clinton also dinged her successor at State, John Kerry, when she stated that she led the ‘last face-to-face negotiations between Abbas and Netanyahu,’ and that ‘Kerry never got there.’ Over the past year, a kind of conventional wisdom developed that Kerry, in particular, reemphasized the Israeli/Palestinian peace process after years of US disinterest. But Clinton is clearly pushing back against that narrative. After all, one of the biggest legacies of her husband’s administration was the 1993 breakthrough that he brokered on the White House lawn between Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin and the leader of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, Yasser Arafat.

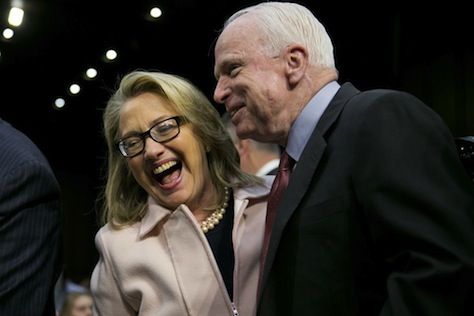

5. She’s now closer to John McCain on Syria

than to the Obama administration.

Though Clinton may be overemphasizing the point, she argued in no uncertain terms that she believes the Obama administration should have armed moderate rebels in Syria shortly after the country devolved into civil war. That echoes the calls of Obama critics like US senator John McCain of Arizona (pictured above with Clinton), who Obama defeated to win the presidency six years ago.

But Clinton’s treatment is incredibly thoughtful and nuanced here, because she admits that she doesn’t know whether arming the Free Syrian Army, for example, would have materially changed the situation in Syria:

HRC: …I can’t sit here today and say that if we had done what I recommended, and what Robert Ford recommended, that we’d be in a demonstrably different place.

JG: That’s the president’s argument, that we wouldn’t be in a different place.

HRC: …So I did think that eventually, and I said this at the time, in a conflict like this, the hard men with the guns are going to be the more likely actors in any political transition than those on the outside just talking. And therefore we needed to figure out how we could support them on the ground, better equip them, and we didn’t have to go all the way, and I totally understand the cautions that we had to contend with, but we’ll never know. And I don’t think we can claim to know.

JG: You do have a suspicion, though.

HRC: Obviously. I advocated for a position.

JG: Do you think we’d be where we are with ISIS right now if the U.S. had done more three years ago to build up a moderate Syrian opposition?

HRC: Well, I don’t know the answer to that. I know that the failure to help build up a credible fighting force of the people who were the originators of the protests against Assad—there were Islamists, there were secularists, there was everything in the middle—the failure to do that left a big vacuum, which the jihadists have now filled.

There’s a credible argument that radical Islamists would have ultimately outmaneuvered the moderate anti-Assad forces eventually anyway, just as we’ve seen in Libya among the anti-Gaddafi forces and as we saw in Mali two years ago. The countervailing argument is that arming Syrian rebels would have amounted to delivering US weaponry directly into the hands of radical groups like Islamic State (الدولة الإسلامية), the former al-Qaeda affiliate that now controls a swath of territory from eastern Syria throughout much of Sunni Iraq, from the western al-Anbar province to Mosul and Tikrit in the north.

You get the sense from this interview that even if you don’t agree with Clinton’s position, she continues to engage the issues honestly and intelligently.

6. She might wind up more hawkish than the Republican nominee.

Imagine for a moment a general election in 2016 where the Republicans have nominated someone like the libertarian-leaning US senator from Kentucky Rand Paul (pictured above), whose non-interventionist foreign policy could place him closer to the Obama administration than to traditional Republican national-security hawks like McCain or former New York mayor Rudy Giuliani.

It’s hard to believe that Paul will successfully win the Republican presidential nomination on his first attempt. But it’s not difficult to imagine that Paul could make a big splash with a growing segment of the American right, especially among the youngest post-Millennial voters who are increasingly willing to give the Republicans a second look — libertarian-minded conservatives skeptical of the post-9/11 security state that’s thrived under both the Bush and Obama administrations and that’s included, at its worst, torture, overreach in Iraq and elsewhere, surveillance abuses and the widespread and controversial use of unmanned aircraft. His candidacy is almost certain to trigger a debate on the American right about security, foreign policy and freedom.

Paul and a Republican electorate weary of foreign adventures could force the Republican nominee to embrace a much more non-interventionist foreign policy than Bush in 2004, McCain in 2008 or former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney in 2012.

Incredibly, that could make Clinton the more hawkish of the two general election nominees in 2016, scrambling long-held generalizations about Republican and Democratic officials. Clinton and Paul both realize this, and both believe it works to their advantage for now. Clinton can use her hawkishness to posture as the somewhat world-weary, experienced old hand; Paul is already effectively using the contrast to draw the brightest line between himself and Clinton as a way of distinguishing himself in what could become a crowded Republican primary campaign.