SAINT-PIERRE — Just off the coast of Newfoundland lies an archipelago of eight attractive if forlorn islands where after a few hours it becomes hard to remember that you’re still in North America. ![]()

![]()

In Saint Pierre and Miquelon, it’s easier to believe that you’ve stepped back in time to the 1970s, perhaps to a sleepy seaside town in northern France. It’s the France that you might remember from your introductory French textbook in grade school (‘Nous sommes à la discothèque de la ville‘)*, but that exists in mainland France, if it ever did, only in the early films of François Truffaut.

For a growing number of tourists to the islands, that’s exactly the point.

Today, the most striking aspect of the small town of Saint-Pierre is the color explosion that characterizes the smattering of houses that climb the hills on the archipelago’s most populous island.

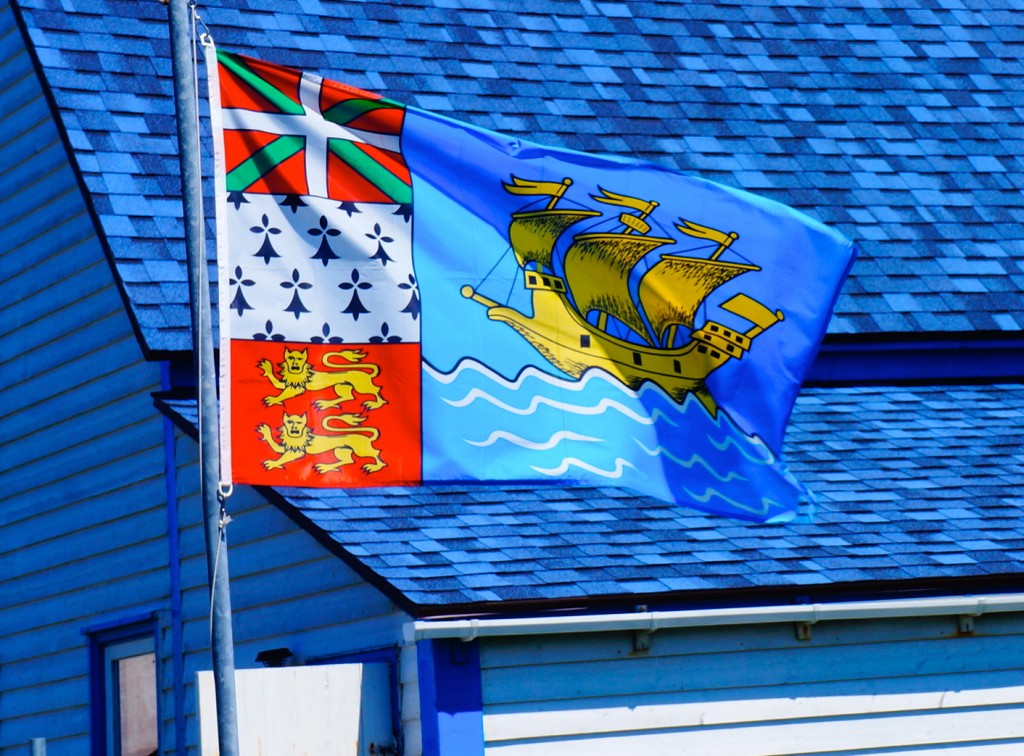

The practice began in the 1960s, at a time when the price of painting became prohibitively inexpensive, which is around the time, ironically, that the islands’ economic self-sufficiency entered what seems like a terminal decline. When the islands had real economic value to France, they were a fog-shrouded enclave of browns and greys, populated by grim Basque, Breton and Norman fishermen (look closely at the collectivity’s flag, certainly one of the world’s busiest, and you’ll find that the three subnational entity flags grace the three squares on the flag’s left side).

The practice began in the 1960s, at a time when the price of painting became prohibitively inexpensive, which is around the time, ironically, that the islands’ economic self-sufficiency entered what seems like a terminal decline. When the islands had real economic value to France, they were a fog-shrouded enclave of browns and greys, populated by grim Basque, Breton and Norman fishermen (look closely at the collectivity’s flag, certainly one of the world’s busiest, and you’ll find that the three subnational entity flags grace the three squares on the flag’s left side).

Saint Pierre et Miquelon’s story is that of fun geographic fluke of the colonial era, in an authentic Settlers-of-Catan kind of way, and Saint-Pierre might be the best stop between Québec and the Breton coast for a decent French croissant. Pro tip: the very best on the island come from the delightful Guillard Gourmandises (pictured below), though I had to wake up early to grab them fresh when the patisserie opened at 7:30 a.m. last Sunday morning.

It all begs the question: Why does Saint Pierre et Miquelon, with a population of just over 6,000, still exist as a freestanding political entity?

Most US and Canadian citizens don’t even realize it exists. Though the islands have their own passport stamp (even Canadians living just minutes away must wade through passport control), it’s not a country but rather a French ‘self-governing territorial overseas collectivity,’ which means that it has more contact with Paris, the French capital that lies 2,650 miles away, than with St. John’s, the Newfoundland capital that lies just 280 miles away.

The islands are home to 4,500 native Saint-Pierrais and 1,500 natives of mainland France, many of whom are serving on the islands as public servants. All of them, however, carry standard French-issued European Union passports, use the euro as currency, not the Canadian dollar, and speak a French language that’s closer to the Parisian dialect than to the distinctive French Canadian you might hear in Montréal or Ottawa. When Saint-Pierrais children finish high school, they don’t trot off to Montréal’s prestigious McGill University or Laval University, or to the University of Toronto or to Memorial University of Newfoundland, they matriculate to universities in metropolitan France.

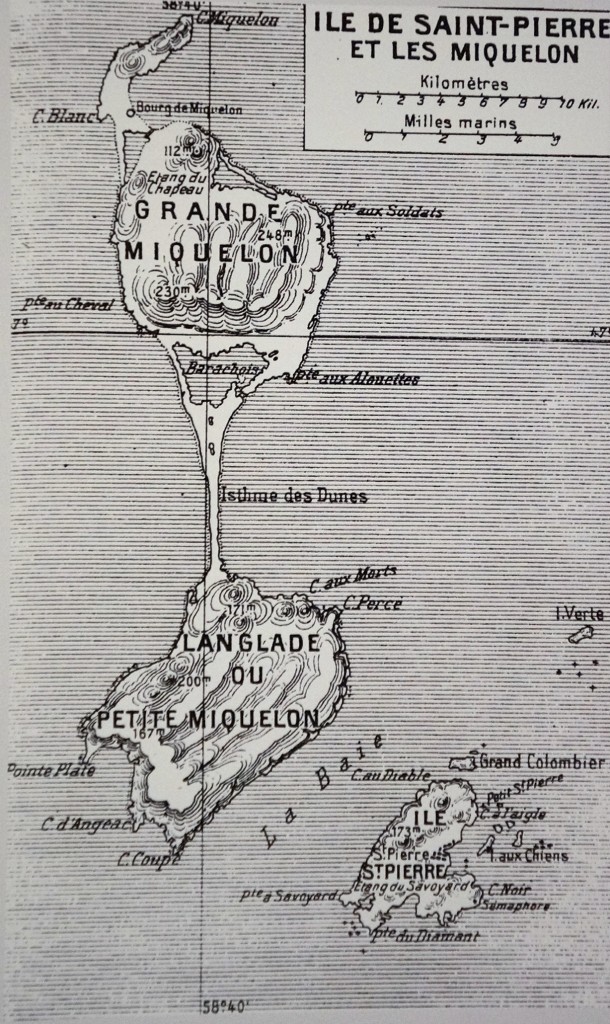

The island of Saint Pierre is smaller in area than the larger islands of Langlade and Miquelon, joined by a sandy, (sometimes walkable) isthmus, but it’s the heart of collectivity, home to the main town and home to all but 500 of the collectivity’s residents.

The islands also appoint one of the 348 members of France’s Senat (Senate) and one of the 577 members of France’s Assemblée national (National Assembly). Its deputy between 2007 and 2014, Annick Girardin, who was born in the Breton town of Saint-Malo, currently serves as a junior minister for development and Francophonie in the cabinet of French prime minister Manuel Valls.

For scholars of Francophone territorial taxonomy, Saint Pierre et Miquelon, as an overseas collectivity, is in the same category as French Polynesia in the south Pacific Ocean (with a population of nearly 270,000) and Saint-Martin (population: 78,000) and Saint-Barthélemy (population: 9,000) in the Caribbean Sea’s Lesser Antilles.

That’s not to be confused with France’s ‘overseas regions,’ which include Guadeloupe (population: 406,000) and Martinique (population: 386,000), also in the Lesser Antilles; Réunion (population: 841,000), an island in the Indian Ocean; and French Guiana (population: 250,000), a chunk of northeastern South America nudged between Brazil and Suriname. Together, France’s overseas departments and territories (DOM-TOM) are home to over 2.7 million people, all of whom are ‘French’ for purposes of proper nationality. Like the rest of the DOM-TOM, Saint Pierre et Miquelon has a local prefect who’s responsible for local government, though France controls larger issues, including defense.

In short, Saint Pierre et Miquelon represents the last vestige of the once great North American empire of New France. Though the Portuguese actually found the islands before either the French or the English, Frenchman Jacques Cartier first stopped here in his 1536 voyage to the continent.

Through the Treaty of Utrecht, however, the British held the islands between 1713 and 1763, when New France reached its apogee. That treaty, which also ceded much of Acadia (much of modern-day Nova Scotia and parts of eastern Québec) and Newfoundland, launching the exodus of Acadians who ultimately settled what would become Louisiana. Though France lost almost all of its North American empire with its defeat to Great Britain in the Seven Years’ War in 1763 (known in North America as the French and Indian War), the Treaty of Paris that ended that war breathed new life into Saint Pierre et Miquelon as a French possession.

Even after the French won the islands back in 1763, they would exchange hands between the British and French a comical number of times in the following half-century, each time necessitating the residents, British or French as they may be, to vacate the islands. During the US war for independence, the British used the opportunity to attack the islands in 1778, bringing them once again under British control.

The 1783 Treaty of Versailles, however, restored the islands to the French. Undaunted, the British tried again in 1793, taking advantage of the tumult of the French revolution to wrest the islands back again. The 1802 Treaty of Amiens restored control to France. The British ultimately reclaimed the islands twice — in 1803 and 1815. But since 1816, France has, in some form, ruled continuously over the islands.

It’s worth noting that because Basque fishermen, from both the French and Spanish Basque regions, also settled in Saint Pierre et Miquelon, 25% of the population throughout the 19th century spoke Basque, and the word ‘Miquelon’ comes from the Basque language. Though no one speaks primarily Basque on the islands anymore, the cultural influence continues today, with Basque descendants flying the flag of the Basque Country/Euskadi and with a fronton, the distinctive court used for the Basque game of pelota, takes up an entire square in the center of Saint-Pierre.

While Canada and Newfoundland, each a dominion of the British empire, could lay claim to many of the waters of North America north of the young United States, giving the British access to cod-rich banks, including the ‘Great Banks,’ that represented some of the richest fishing waters in the world, Saint Pierre et Miquelon gave France a claim to those waters as well. Though it’s perhaps difficult today to realize, those fishing waters meant a great deal for a 19th-century economy with limited access to meat, above all a Catholic country that preferred fish every Friday. Until the turn of the 20th century, the islands were an economic bounty for France, which sent fishermen to trawl the waters every summer alongside permanent residents for cod, which was subsequently salted and dried on ‘graves’ of stone in the northern summer sunlight before being exported to France.

As you might imagine, relations with Canada over fishing rights have been dicey over the years. In 1887, for example, the Newfoundland Bait Act made it illegal for Canadians to sell bait to fishermen from France and from Saint Pierre et Miquelon. US senator Henry Cabot Lodge, a Massachusetts Republican, even argued for the US annexation of the islands. A new treaty between Great Britain and France over fishing rights in 1904 severely limited the ability of French fishing in the area — the population dropped from nearly 7,000 to just 4,000 in a few short years, beginning what would be a gradual decline in the archipelago’s economic viability.

Furthermore, World War I intruded on the quiet life of the islands in 1914, and 105 residents died in Europe fighting for France. A graveyard commemorates them on the relatively abandoned island of L’Île-aux-Marins, just a ten-minute boat ride from the main island of Saint Pierre, and a beehive of activity at the height of the cod fishing industry. Today, it’s one part ghost town, one part historical curiosity and one part summer refuge for a smattering of Saint-Pierre residents. Until 1935, the island was called the Île-aux-Chiens, or ‘Island of the Dogs.’ Somewhat curiously, dogs are now prohibited on the island.

Subdued by setbacks in the fishing industry and the war effort, the islands wouldn’t have to wait too long for a new boondoggle this time in the form of liquor. Upon the passage of the US constitution’s 18th amendment and the Volstead Act in 1920, the era of Prohibition placed a high premium on smuggled alcohol. That left Saint Pierre et Miquelon perfectly placed as a transshipment point for booze on its southbound path to the United States. Imported from Canada, France and elsewhere in Europe, smugglers — including Al Capone, the most infamous of the Prohibition-era bootleggers — would pack bottles of whiskey, wine and everything else on boats in Saint-Pierre, leaving the cumbersome and noisy wooded crates behind. It’s said today that a fair share of the island’s wooden homes were built from the remants of the alcohol trade during Prohibition.

Though the end of Prohibition in the United States in 1933 meant the end of a decade of thriving illicit trade for the islands, Saint-Pierre played something of a notorious role in World War II. Though its prefect sided with the collaborationist Vichy government in France in 1941, general Charles de Gaulle, then leader of the Free French, organized an invasion to retake the islands, unbeknownst to US president Franklin Roosevelt. Roosevelt British prime minister Winston Churchill, likely gauging an opportunity to bring the islands into the Anglo-American sphere, had been discussing an invasion of their own. They were as surprised as everyone else when the Free French made Saint Pierre et Miquelon one of their first victories in rolling back the Vichy regime. The Christmas Eve invasion in 1941, led by Amiral Muselier, was a military and tactical success for de Gaulle, but his maverick operation, for which he hadn’t bothered notifying FDR or Churchill, permanently soured FDR on the French general’s judgment and trustworthiness. Today, however, the main square in Saint-Pierre is named for de Gaulle.

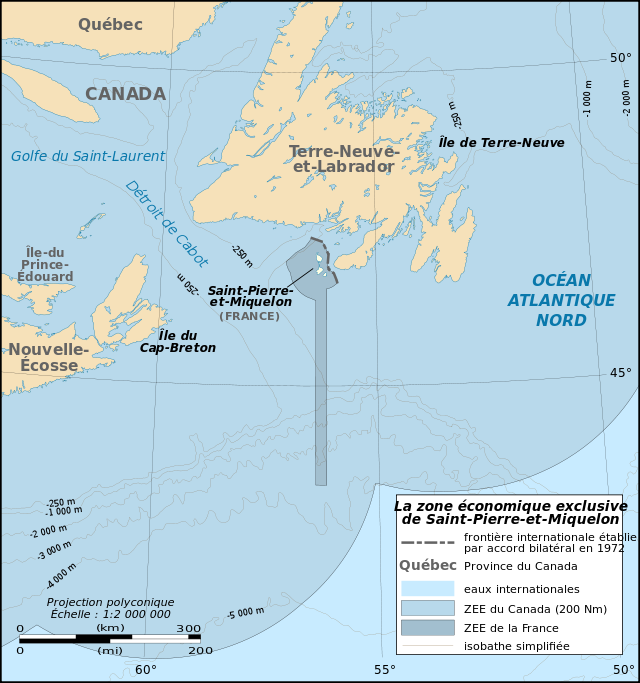

Though the islands tuned back to fishing as the chief economic activity in the postwar period, centuries of overfishing throughout the entire area had depleted cod stocks. A decision by the International Court of Justice in 1992 in a dispute between Canada and France (on behalf of the collectivity) left the islands an exclusive economic zone that runs 200 miles south, but just 10 miles wide, a zone that locals refer to disparagingly as the ‘baguette’:

That decision came the same year that the federal Canadian government ordered a moratorium on cod fishing off the coast of Newfoundland, sinking Canada’s easternmost province into an existential economic crisis. Whereas Newfoundland is now turning to offshore oil exploration to boost its economy, the 1992 ICJ decision means that Saint-Pierre’s dream of mineral wealth rests solely upon the chance that significant oil lies within the ‘baguette’ of its exclusive economic zone. That’s something of an insult for a community that’s been tied to the sea for centuries.

In the meanwhile, it costs the French government tens of millions of euros to subsidize the islands. A ship arrives from Halifax every week with fresh goods, but Saint Pierre et Miquelon still obtain many of their necessities — from cars to wine — from France. Remarkably, 68% of imports come from France, with just 23% coming from Canada. Increasingly in the past decades, economic development depends on large public works projects, such as an extension of Saint-Pierre’s port in the 1960s, a new airport in the 1990s, and more recently, a housing development and a new power plant (in truly retro French style, the island’s power is 100% diesel-based). You can easily imagine projects in alternative energy, such as wind, or oil exploration, for decades to come.

Nevertheless, from any economic standpoint, France’s investment in Saint Pierre et Miquelon would appear wholly irrational today, and I found myself wondering the whole time I was in Saint-Pierre what exactly France gets out of the arrangement today. If it made economic sense in the 18th and 19th centuries and, arguably, geostrategic sense in the 20th, the islands hold no real utility for France in the 21st century, barring some major oil bonanza or tourism boost. Can it be solely the pride of sovereignty? Why, after all, does the United Kingdom still care so much about 4,700 square miles of islands off the Argentine coast?

Chalk it up to the ghost of colonial pride. Or preserving cultural heritage. Or any of the other economically irrational reasons that win out for the sake of politics, sentimentality or even just the simple joy of maintaining a French jewel in the North Atlantic.

* * * * *

* Yes, there’s really just one major discotheque in the city, and the ‘step back in time’ effect was greatly enhanced by the fact that after more that two hours of music and revelry, I didn’t see anyone pull out a single smartphone. They also still play Partenaire Particulier.

Excellent article, and beautiful photos, thanks!

A couple of remarks, on transportation and maritime economic zones (EEZ):

Saint-Pierre & Miquelon has its own airline, Air Saint-Pierre, which serves every week the airports of Montreal, QC, Halifax, NS, and Saint-John’s, NL.

Besides, and in addition to the freighter which does a weekly service between Halifax, NS, and Saint-Pierre, there is also a fast ferry, the mv Cabestan, which plies daily between Saint-Pierre and the port town of Fortune, which is 25 miles away from Saint-Pierre, on the Burin peninsula, on Newfoundland southern coast, a 4 1/2 hours’ drive from Saint-John’s. There is also a second freighter ship, currently the mv Aldona, which also plies between Saint-Pierre and Fortune, NL.

As to the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), France has publicly indicated in 2013 that it is in the process of building a file on Saint-Pierre & Miquelon with the UN “Commission on the limits of the continental shelf” which judges EEZ cases based on the UN “Law of the Sea”.