It ultimately took an American hedge fund to unite the Argentine people behind the increasingly unpopular presidency of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner.![]()

Now, after a prolonged fight that has its roots in Argentina’s last debt default over a decade ago, a fight that has weaved its way through the corridors of power in Buenos Aires, via the banks of New York and London, into the highest court of the United States, and with consequences that will reverberate from Brasília to Caracas, Argentina is now defaulting, once again, on its debt obligations.

How did Argentina end up in this situation? And what will happen if Argentina, which technically entered default at midnight earlier today, doesn’t arrive at a deal with its creditors?

Here’s a primer on everything you need to know about the Argentine default — and why it’s such an odd, twisting and ultimately fascinating story about Latin American politics, global finance, US constitutional law and the ‘north-south’ dynamic of international relations.

So what exactly does Argentina owe?

The current fight between Argentina and its creditors goes back to the Argentine government’s 2002 default. In the middle of a severe economic crisis, Argentina defaulted on $82 billion in sovereign debt. By 2005, president Néstor Kirchner’s government agreed to a restructuring of that defaulted debt, a deal that was generally seen as very good for the Argentine government. Around 76% of the bondholders ultimately agreed to exchange their bonds for payment far below the value of those bonds — generally between just 25% to 35% of their face value.

But that still left holdouts and, in January 2010, the government of his widow, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, held another restructuring.

As a result of the two restructurings, only about 7% of the original debt amount remains, and it’s held by creditors who refuse to take haircuts on the debt, instead demanding payment in full, with interest from 2002. The current default deals with just that final 7%.

How did this US hedge fund become such a central character in Argentina’s default?

In 2008, NML Capital, a hedge fund controlled by Elliott Management and managed by New York financier Paul Singer, bought some of the Argentine debt from among the holdouts. Today, Argentina owes Singer and Elliott around $1.6 billion.

Singer and his colleagues at Elliott took a particularly aggressive view to collecting on the debt — at one point, Singer even tried to seize an Argentine naval vessel at a port in Ghana and attempted to impound Kirchner’s presidential airplane.

Given that the debt was issued under New York law, Singer then decided to sue Argentina in New York federal court to compel the government to pay Elliott Management before paying any of its other creditors, by means of an injunction that prohibited leading New York banks from delivering Argentina’s payment to other creditors. Griesa essentially agreed with Singer, not with Argentina, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, incredibly, upheld the decision, and the US Supreme Court declined to reconsider the Second Circuit’s ruling.

Other elements of the case did make it all the way to the Supreme Court, where Argentina also lost, notwithstanding the fact that the Obama administration supported Argentina’s view of the substantive law.

The deadline for Argentina to pay the first installment, around $589 million, which has already been placed in an escrow account by the Argentine government, was on July 1. The grace period extended through July 30. But not surprisingly, the two sides didn’t reach a deal, so Argentina is technically now once again in default.

Why doesn’t Argentina want to pay?

Fernández de Kirchner, who was first elected president in 2007 and reelected in 2011, has politicized the issue as a matter of sovereignty. Given the cast of characters that she has to work with — Singer, hedge funds and New York courts — it would almost be political malpractice not to rail against them as predatory villains.

Thomas Griesa, for example, the judge for the Southern District of New York who issued the first ruling in favor of Elliott and against Argentina, is one of the most hated men in Argentina today. It seems like every sentence uttered by Fernández de Kirchner these days contains the words ‘fondo buitre‘ (Spanish for ‘vulture fund’).

Though Fernández de Kirchner hoped to convince the Argentine Congress to amend the constitution to allow her to run for a third term as president, that now seems very unlikely and, barring extraordinary circumstances, she will leave office after the October 2015 election to choose her successor. She’ll do so as a relatively unpopular figure, in part because Argentina has been frozen out of international debt markets, and she’s been forced to pursue unorthodox avenues to fund a populist spending agenda. That included nationalizing Argentina’s pension funds and an unsuccessful attempt in 2008 to impose an agricultural export tax, which backfired spectacularly when farmers from across the country descended in protest on Buenos Aires.

Does Kirchner’s position have to do with her leftist politics?

Can’t we blame it on ‘peronismo’?

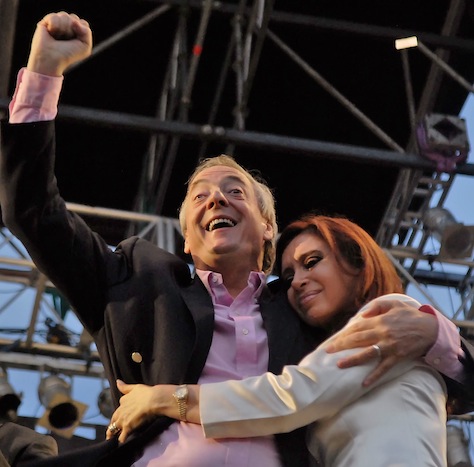

Fernández de Kirchner, like her husband before her, espouses a generally leftist view of foreign policy that’s brought Argentina much closer to socialist counties like Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador than to the United States. Two of her chief allies in South American politics include two ardent leftists, Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro and Uruguayan president José Mujica (pictured above with Kirchner).

Like just about every successful Argentine politician since the 1940s, the Kirchners made sure to couch their policies under the banner of peronismo. Today, it’s sort of a mystery just what peronismo entails, and even leading opponents of the Kirchners, such as former Kirchner ally and Tigre mayor Sergio Massa take care to described themselves as peronistas. The reality is that even under its namesake, former president Juan Perón, peronismo incorporated a dizzying amount of ideological flexibility.

Fernández de Kirchner appointed the young, leftist firebrand Axel Kicillof as her finance minister last November in anticipation of the coming debt fight. Prolonging the struggle against ‘foreign speculators’ is good politics for Kirchner — so long as Argentina’s latest default doesn’t plunge the broader economy into deep recession.

So that’s the only reason Argentina’s holding out? Populist politics?

No, not exactly. There’s also a really good financial reason for Argentina to hesitate.

The terms of the deals that Argentina made with the other 93% of its one-time bondholders include something called a RUFO (Rights Upon Future Payments) clause, which provides that if Argentina gives Singer and the hedge funds a better deal, Argentina will have to go back and give the other 93% of the bondholders the same deal, which could cost hundreds of billions of dollars. Given that Argentina has around $29 billion in foreign reserves, it’s a result that could wipe out the country’s finances.

That clause expires at the end of 2014, however, so Argentina is desperate for a deal that doesn’t take effect until at least January 1, 2015.

Now what exactly happened in 2002? How did the Kirchners end up so powerful for a decade?

Argentina first defaulted on its sovereign debt amid an economic crisis that stemmed from its infamous ‘convertibility’ policy that pegged the Argentine peso to the US dollar throughout much of the 1990s, a strategy that met with great approval from the International Monetary Fund and other leading neoliberal institutions. It was the apex of the ‘Washington Consensus,’ after all, and Argentina was, for a while, a shining case study. In the wake of financial crises in Russia and Asia, investors became skeptical that Argentina’s peso should be valued at par with the US dollar. Their actions forced the Argentine treasury to spend its foreign reserves on an improbable attempt to maintain the peso‘s value. Probably the best detailed treatment of the Argentine crisis is Paul Blustein’s book, And the Money Kept Rolling In (and Out).

When Argentina failed, it resulted in a severe economic recession that reached its nadir in 2002, when the country suffered a 10.9% contraction.

The resulting economic pain swept away the old guard that had governed Argentina since the end of the notorious military regime that collapsed in 1983 (a regime that, among other things, decided that it was a good idea to launch a war with the United Kingdom over the Falkland Islands). The implosion of the country’s political elite between 1999 and 2001 paved the way for the rise of Néstor Kirchner, the formerly little-known governor of Santa Cruz province. To get a sense of just how obscure Kirchner really was, consider this: Río Gallegos, the capital of Santa Cruz, is actually closer to Antarctica than it is to Buenos Aires.

Nevertheless, Kirchner was acclaimed president in 2003 after his challenger, disgraced former president Carlos Menem, withdrew from the race. In January 2005, Kirchner led the Argentine government in its first debt restricting, holding firm to the harsh terms that many creditors ultimately accepted, winning Kirchner acclaim domestically. That propelled his wife to victory in the 2007 presidential race. (Néstor died of a sudden heart attack in October 2010, which upset the couple’s plans to trade off the presidency every other term.)

Whew. That’s a lot of information. I know this isn’t a Max Fisher explainer, but can we have a music break?

Sure! Argentina has some of the best music in the world, given that the tango tradition originated in Buenos Aires’s La Boca neighborhood, which, for all its working class roots, is now a colorful tourist attraction (pictured above).

Some of the best music recently coming of the Argentine tradition is electronic/tango fusion, and no one does it better than the Paris-based Gotan Project (Gotan — get it? Tan-Go backwards). Here’s one video from 2010:

If you’re looking for something a little more traditional, you can’t do any better than Astor Piazzolla, who’s essentially the Mozart of the modern tango tradition:

Just what I needed. Now, back to the default. Why exactly did the US Supreme Court get involved in the case?

Before going any further into the US legal issues, you should watch financial writer Felix Salmon’s Lego-based explainer of the law involved, back when he was still at Reuters. No one knows this aspect of the Argentine default better than Salmon, whose six-minute primer should go down in history for the humor and clarity it uses to explain a complicated matter:

Roughly speaking, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals upheld Griesa’s decision that Argentina must pay what it owes Elliott Associates and the 7% holdouts before it can pay any of its other creditors. In other words, all bondholders must be treated on what lawyers refer to as a pari passu basis, meaning that Argentina must treat them all equally.

But in essence, that gives a New York district court the ability to override the sovereign immunity of a state like Argentina. Before the ruling, a country’s leaders could decide when, how and if to pay its creditors entirely on the basis of its own policy preferences. After the decision, a New York court can scramble that country’s ability to pay any of its creditors, so long as its funds are routed through New York banks. You can understand why so many stakeholders had a problem with this decision and why any government, including the US government, would be so uneasy with the consequences that follow from the decision.

For the world of sovereign debt beyond Argentina, the decision provides many more questions than answers.

So now that Argentina has defaulted, is it headed for another economic collapse?

A technical default on a small payment mandated by a controversial judicial decision is a lot different than a widespread default on $82 billion. It’s a much less traumatic ‘default’ than the one in 2002, so much so that Kicillof (pictured above) called it an ‘atomic nonsense’ and argued that the July 30 event isn’t a default, but rather ‘collection problems due to a judiciary sentence.’

Traditional debt markets closed to Argentina 13 years ago, so there’s really nothing to lose in that regard, either. It’s also true that the world is a much different place today than it was in 2002, so Argentina can turn to alternative sources of finance, including lending from the People’s Republic of China, the Middle East or elsewhere.

The real damage to the Argentine economy, which isn’t in particular great health these days, could come from a further devaluation of the Argentine peso in global currency markets. Many emerging market currencies have lost value this year, and Argentina’s is no exception, shedding 25% of its value against the US dollar. If the peso drops lower, it will spur even more inflation, a recurring theme in the Argentine economy over the past decade, a problem that government statistics widely understate. The economy is already either at zero growth or in recession, and the official 7.1% unemployment rate may also understate the actual jobs scenario.

So while it’s not likely that Argentina will see a repeat of its 2001-2002 contraction, none of this will help the economy, which is essentially tied with Colombia as Latin America’s third-largest, after Brazil and México.

What does all of this mean for Latin America and the world, generally?

So long as Argentina continues to thumb its nose at the United States and hobgoblins like ‘vulture funds’ and ‘speculators,’ it will certainly be encouraged by leaders like Venezuela’s Maduro, who view it as a great opportunity to show solidarity against the perception of US interference in Latin America.

For the rest of the world, there’s relatively little exposure to Argentine debt because, well, there’s been no global market for Argentine debt in the past 13 years. Argentina’s default, as Matt Levine writes for Bloomberg View, could accelerate payments due to the 93% of those creditors who have made deals with Argentina, but of course, the Griesa ruling forbids any payments to them until and unless Argentina pays Elliott and the 7%. So everything has come to a screeching halt until the parties reach deal.

Perhaps the most significant outcome is for any third-party actors who hold credit default swaps on Argentina’s potential default. Essentially, financial actors can enter into contracts with other financial actors that provide for certain payouts if and when Argentina is found to have defaulted. With around $1 billion in estimated CDS obligations revolving around Argentine default, that means the most important decision lies not with the Argentine government or Elliott and the creditors, but with a rather obscure committee of the International Swaps and Derivatives Association, which the financial world has generally agreed gets to decide these kind of things.

As noted above, the long-lasting impact of this saga lies in the gigantic hole of uncertainty that the Griesa and Second Circuit decisions have blown into the world of sovereign debt, which could make New York a much less attractive venue in the future.