With US and Iranian officials publicly pressuring Iraq’s parliament to form a new national unity government as quickly as possible, Sunni and Kurdish (and, increasingly, many Shiite) leaders seem united on one thing — they’re not enthusiastic about giving Iraqi prime minister Nouri al-Maliki a third term in office.![]()

Iraq’s parliamentarians took a small step toward forming a new government yesterday when they elected Salim al-Jubouri as the new speaker of the 328-member Council of Representatives (مجلس النواب العراقي). In post-Saddam Iraq, the speakership is reserved for a Sunni, the presidency is reserved for a Kurd, and the premiership for a Shiite. Each official has two deputies such that each group — Sunni, Shiite and Kurdish — winds up with one major office and two deputy offices. Accordingly, when the Iraqi parliament chose Jubouri as the speaker, it also chose his two deputies.

It was the vote to appoint Iraq’s Shiite deputy speaker, however, that may hold some clues to the rest of the government formation process. The new speaker has fully two weeks to nominate a candidate for the Iraqi presidency, which means it could take a full month to appoint the president who thereupon has another 15 days to appoint a prime minister.

Though Haidar al-Abadi, a Maliki ally, ultimately won the deputy speakership, he faced an unexpectedly stiff challenge from Ahmad Chalabi, who’s gunning for the premiership.

* * * * *

RELATED: Don’t blame Obama for Iraq turmoil — blame Maliki

* * * * *

There’s been a considerable amount of chatter inside and Iraq about the sudden rehabilitation of Chalabi, a figure upon whom US officials relied heavily in their decision to launch a military invasion against Saddam Hussein in 2003. But for all the talk of his sudden rise, he remains a longshot to become Iraq’s next prime minister.

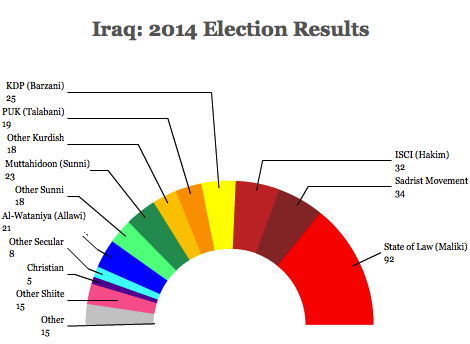

All the same, Abadi’s rise also signals that Maliki won’t continue as Iraq’s prime minister, either. Abadi is not only a member of Maliki’s State of Law Coalition (إئتلاف دولة القانون), he’s a member of Maliki’s party, Islamic Dawa (حزب الدعوة الإسلامية). In April’s parliamentary elections, which now seem a lifetime ago in Iraqi politics, Maliki’s State of Law Coalition (SLC) won 92 seats, by far the largest bloc in the parliament, itself holding a majority within the Shiite majority. Though , the State of Law Coalition will continue to drive the process within the Shiite bloc, generally, it’s farfetched to think that other SLC leaders, not to mention the legislators of the two other Shiite groups, Muqtada al-Sadr’s Sadrist Movement (التيار الصدري) and Ammar al-Hakim’s Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ICSI, المجلس الأعلى الإسلامي العراقي), would agree to hand over two of the three top offices, including the premiership to Islamic Dawa.

That makes it very likely that the Shiite leadership will turn to another figure, such as Iraq’s former oil minister, deputy prime minister and, as of four days ago, its new foreign minister, Hussain al-Shahristani (pictured above), who is a top SLC figure from outside Islamic Dawa.

SLC’s strength means that it will still likely produce Iraq’s next prime minister, even as Sunni and Kurdish (and other Shiite) leaders, not to mention US and Iran officials, are taking a stronger line that Maliki must go. Even Ali al-Sistani, Iraq’s leading Shiite cleric, who largely stays out of day-to-day political matters, has signaled that he, too, opposes Maliki’s reelection.

Despite campaigning as a nationalist leader in the 2010 parliamentary elections and assembling a national unity government, both Sunni and Kurdish leaders resent the Maliki administration for its failure to share true power across ministries, instead centralizing as much power as possible — power ultimately wasted on corruption or ineffective governance.

Sunni leaders, many of whom oppose the rise of the hardline Islamic State (الدولة الإسلامية), formerly ISIS or ISIL, are angry at Maliki’s increasingly sectarian rule, nevertheless frowned upon Maliki’s decision to attempt to use force to eject ISIS from Fallujah and Ramadi in January. That severed what remaining goodwill existed for Maliki within the Sunni community, especially after Maliki essentially exiled Iraq’s Sunni vice president Tariq Hashemi.

For all their internal differences, Kurdish leaders, who only last month finalized a regional government after last autumn’s Kurdish election, remain universally angry with Maliki. They’re mostly disenchanted with Baghdad’s inability to attract investment for ramping up oil production, and Maliki’s simultaneous unwillingness to permit the autonomous Iraqi Kurdistan region to accelerate its own oil production efforts independent of Baghdad. When Kurdish leaders moved forward with a pipeline last year linking Kurdish oilfields directly to Turkey, Maliki stopped payment of what had become a customary 17% share of the Iraqi national budget.

But in the arithmetic of forming a new Iraqi government, a wholly united Sunni bloc would hold just 41 seats and a united Kurdish bloc just 62. Meanwhile, Shiite legislators hold 176 seats in the 328-member Council. Secular parties hold another 29 seats, Christians have five seats reserved for them, and other reserved groups and independents hold the rest.

The obvious difficulty is that while a united Shiite bloc could easily name a prime minister, it’s currently far from united. Neither, by the way, are the Sunni and Kurdish blocs. But Abadi’s appointment this week as deputy speaker might indicate that there’s a working majority of Sunni, Shiite and Kurdish legislators opposed to a third term for Maliki.

If not Maliki, who?

The inestimable Kirk Sowell argues that there are now essentially three major contenders, with some room for a potential surprise.

The first is former prime minister Ibrahim al-Jaafari, who governed Iraq in a tumultuous year from May 2005 to May 2006. Once the secretary-general of Islamic Dawa, Jaafari formed his own party in 2008, the National Reform Trend, so while he’s no longer associated with Islamic Dawa, he remains a key SLC leader. Though his record as prime minister isn’t incredibly distinguished, the intervening eight years, and Maliki’s current missteps may place Jaafari in a better light.

The second is Falih al-Fayyad, Maliki’s national security advisor, though he hasn’t exactly been successful over the past four years, either in Iraq or in efforts to bring Syria’s warring parties into negotiations.

The third is Shahristani, who served as oil minister between 2006 and 2010 and as deputy prime minister since 2010. When all of the Kurdish ministers resigned last week, including foreign minister Hoshiyar Mebari, Maliki appointed Shahristani as foreign minister in the caretaker government that will continue to reign until the Iraqi parliament elects a permanent one.

An engineer who served in a minor capacity in Saddam’s Baathist government in the 1970s, his opposition to Saddam’s nuclear weapons program landed him in the infamous Abu Ghraib prison for over a decade. He escaped to Canada in 1991 amid the Gulf War, returning to Iraq in 2003.

Though Shahristani often tangled with the Kurdish regional government over oil revenue-sharing and other messy issues during his tenure as oil minister, he has a strong relationship with Jalal Talabani, the current Iraqi president and the leader of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK, یەکێتیی نیشتمانیی کوردستان), one of the two traditional powers in Kurdistan. If Talabani can bring along Massoud Barzani, the leader of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP, پارتی دیموکراتی کوردستان) and the Kurdish regional president, Shahristani could emerge as the candidate who could unite all three camps — at least in contrast to Maliki.

Photo credit to Sabah Arar / AFP/ Getty Images.