Depending on your age, your nationality and your perspective, you’ll remember Eduard Shevardnadze, who died three days ago, as either a progressive reformer who, as the Soviet Union’s last foreign minister, helped usher in the period of glasnost and perestroika under Mikhail Gorbachev that ultimately ended the Cold War, or a regressive autocrat who drove Georgia into the ground, left unresolved its internal conflicts, and ultimately found himself tossed out, unloved, by the Georgian people after trying to rig a fraudulent election in a country was so corrupt by his ouster that the capital city, Tbilisi, suffered endemic power outages.![]()

![]()

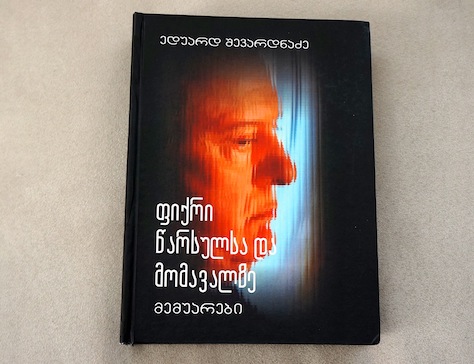

Both are essentially correct, which made Shevardnadze (pictured above) one of the most fascinating among the final generation of Soviet leadership. It’s not just a ‘mixed‘ legacy, as The Moscow Times writes, but a downright schizophrenic legacy.

His 2006 memoirs, ‘Thoughts about the Past and the Future,’ have been sitting on my bookshelf for a few months — I ordered the book from a Ukrainian bookstore, and I hoped to find a Georgian language scholar to help translate them. I would still like to read an English translation someday, because I wonder if his own words might offer clues on how to reconcile Shevardnadze-as-visionary and Shevardnadze-as-tyrant.

Gorbachev and Russian president Vladimir Putin had stronger praise for Shevardnadze than many of his native Georgians:

Gorbachev, who called Shevardnadze his friend, said Monday that he had made “an important contribution to the foreign policy of perestroika and was an ardent supporter of new thinking in world affairs,” Interfax reported. The former Soviet leader also underlined Shevardnadze’s role in putting an end to the Cold War nuclear arms race.

President Vladimir Putin expressed his “deep condolences to [Shevardnadze’s] relatives and loved ones, and to all the people of Georgia,” his spokesman Dmitry Peskov said. Russia’s Foreign Ministry also issued a statement on Shevardnadze’s passing, saying the former Georgian leader had been “directly involved in social and historical processes on a global scale.”

Even Mikheil Saakashvili, who came to power after Georgians ousted Shevardnadze in 2003’s so-called ‘Rose Revolution’ had somewhat generous, if begrudging, words for the former leader:

…Saakashvili said that Georgia’s second president was “a significant figure for the Soviet empire and for post-Soviet Georgia.” He said that historians will have to work for a long [time] to “assess more precisely the role” of Shevardnadze.

Shevardnadze served as the Soviet Union’s foreign minister between 1985 and 1990 and who served as the general secretary of the Georgian Communist Party from 1972 to 1985, making him the de facto ruler of the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic throughout much of the Soviet Union’s sclerotic decline under the aging Leonid Brezhnev. Though he rose though the ranks in the rigid Soviet hierarchy as a Brezhnev sycophant, he won the top job in Georgia on the merits of his successful anti-corruption campaign, the first of several hints of the reformist role he would eventually play at the national level. He was a more capable economic steward and a more liberal autocrat, as far as Soviet republic-level secretaries go. He served as a skillful interlocutor between the Soviet leadership and Georgian protesters in 1978, who demanded that Georgian remain the sole language within the GSSR.

When Gorbachev came to power in the Soviet Union in 1985, he and Shevardnadze formed the core, along with Boris Yeltsin and Alexander Yakovlev, of the liberal reformist camp within the Soviet Politburo. It was a battle that, even as general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Коммунистическая партия Советского Союза), Gorbachev would struggle to win. As foreign secretary, Shevardnadze forged strong relationships with two US secretaries of state, George Shultz and James Baker, leading to détente, as well as a series of nuclear anti-proliferation agreements, that would have been unthinkable upon Ronald Reagan’s election to the US presidency in 1981.

In the face of a growing conservative backlash against Gorbachev’s reforms and the rising tide of Baltic independence and calls for greater autonomy and freedom in eastern Europe, Shevardnadze dramatically resigned as foreign minister in December 1990, sounding alarms against hardliners that would have been unthinkable among previous generations of Soviet leadership, in essence predicting the August 1991 coup against Gorbachev that would follow.

As David Remnick writes in his indispensable work on the end of the Soviet Union, Lenin’s Tomb: The Last Days of the Soviet Empire, Shevardnadze’s resignation stunned the world:

Shevardnadze had warned that ‘dictatorship is coming and that the democrats had scattered ‘to the bushes.’ Shevardnadze had not told anyone that he would make his speech except his family and a couple of his closest aides. As he spoke, his Georgian accent made thicker by the anger in him, the sense of moment, Gorbachev sat at the Presidium as shocked as anyone else in the hall. It was one thing for Moscow intellectuals at the kitchen table to talk about a nascent dictatorship, quite another for Shevardnadze, the second-most-recognized face in the leadership, to put an end to his career.

When he returned to Georgia in 1992, he found a nation, suddenly independent, in chaos. Though he eventually consolidated power by 1995 to become Georgia’s president, it came only after a bloody coup in 1992 to oust Sviad Gamsakhurdia, a Georgian nationalist and Shevardnadze opponent in the Soviet era, and civil war that ended only after Russian intervention on his behalf. He also faced significant unrest in the Russian-majority enclaves of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, which would, of course, force another national crisis over a decade later.

As Natalia Antelava writes in The New Yorker, it’s not that Shevardnadze didn’t have achievements in post-Soviet Georgia, it’s that they were so overshadowed by his shortcomings:

Shevardnadze, as Georgians saw it, was born in a small village, the son of a teacher, and joined the Communist Party at the age of twenty and then ascended global heights. They wanted him to do so again and bring the country with him. He brought bitter disappointment. Instead of prosperity, he ushered in a decade of corruption, nepotism, and missed opportunities. Every achievement of Shevardnadze’s rule was offset by a great failure: He ended a civil war, but allowed lawlessness and violent crime to rule. He signed some pro-Western reforms, but Georgia approached the very top of Transparency International’s corruption index. His connections in the West helped him turn Georgia into one of the largest per-capita recipients of U.S. aid, but little of it reached the population. He introduced the national currency, the lari, but the economy was in tatters.

As president, he was powerful enough to hew a careful balance among Russia, the United States and the European Union, a gracefulness that his successor Saakashvili lacked, which became horribly apparent when Saakashvili misjudged Russia in the 2008 crisis over Abkhazia and South Ossetia. In many ways, it was Shevardnadze that set Georgia on its path today, with its hopeful eye turned west and to eventual NATO and European Union membership with a zeal that hasn’t rooted in Armenia and Azerbaijan, its neighbors in the Caucasus.

Yet Shevardnadze wasn’t strong enough to nourish the rule of law within Georgia, and under his reign, democracy faltered and corruption soared. By the time that Saakashvili took power in 2003, Georgia was an utter mess economically, legally and politically, much of it due to the neglect or outright graft of Shevardnadze’s circle. When the end came, following a comically transparent attempt to steal the December 2003 parliamentary elections and the first of several ‘color revolutions’ in the former Soviet Union, he wisely stepped down rather than force a bloody confrontation with protesters.

For all his faults, Saakashvili, nine years later, will be remembered as the leader who secured the foundations of Georgian democracy when he admitted defeat and facilitated an orderly, peaceful transfer of power after the anti-Saakashvili coalition, Georgian Dream — Democratic Georgia (ქართული ოცნება–დემოკრატიული საქართველო) defeated the ruling United National Movement (ერთიანი ნაციონალური მოძრაობა) in the October 2012 parliamentary elections.

It could have been Shevardnadze, and it should have been Shevardnadze, to set that precedent. If he had recognized that he had lost the confidence of the Georgian people and acted accordingly, he would be remembered this week as the father of the modern Georgian nation.

Instead, his legacy will always be much more complex.

What does that mean for Georgia today in 2014?

Perhaps the most important challenge for Georgia’s new, young prime minister, Irakli Garibashvili, an ally of former prime minister Bidzina Ivanishvili, the powerful businessman who bankrolled the Georgian Dream coalition, is to embody the best of both of his predecessors — to embrace the modernizing zeal of Saakashvili, the anti-corruption reformism of GSSR-era Shevardnadze and the statesmanlike foreign policy of the post-independence Shevardnadze.