Heading into Thursday’s provincial elections, polls showed that both the center-left Liberal Party of Ontario and the center-right Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario (PC) both had a chance of winning at least a minority government.![]()

![]()

Late-breaking polls on Tuesday and Wednesday, however, showed the Liberal vote creeping up, matched by a decline in support for the progressive alternative, the New Democratic Party of Ontario (NDP).

As it turns out, those late polls were spot on, and Ontario’s new premier Kathleen Wynne, who inherited a minority government from her predecessor Dalton McGuinty just 16 months ago, reinvigorated Ontario’s Liberals and won a majority government in her first campaign leading the party.

* * * * *

RELATED: Meet Kathleen Wynne, Ontario’s premier and the 180-degree opposite of Rob Ford

* * * * *

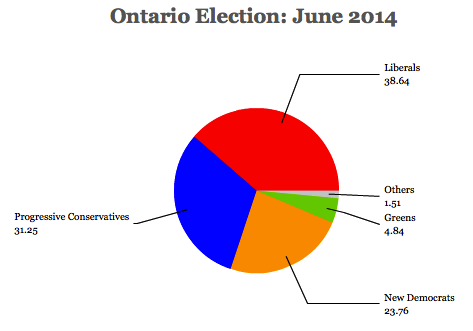

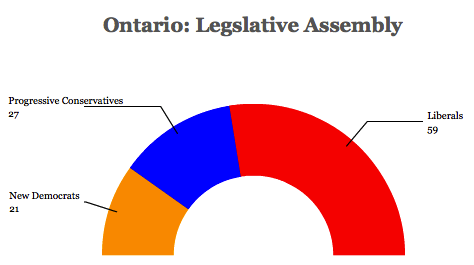

The Ontario Liberals won 59 seats in the 107-member Legislative Assembly with nearly 39% of the vote, while the Ontario PC won just 27 seats with just over 31% of the vote, a nearly disastrous result that found the Tories losing ground in what was shaping up as a PC landslide a year ago:

It’s an unexpected trajectory for a party to go from two terms of majority government to one term of minority government and, then, back to a majority government. Part of the reason is that Ontario’s voters simply never warmed to PC leader Tim Hudak.

Hudak has already stepped down as leader after five years at the helm, including two campaigns that saw the Progressive Conservatives blow early polling leads. In the current campaign, Hudak championed a red-meat conservatism that, despite trumpeting a plan to create one million jobs in the province, pledged to simultaneously cut 100,000 jobs from Ontario’s public sector, reduce bureaucracy and slash the Ontario budget deficit in two years (Wynne and NDP leader Andrea Horwath both pledged to reduce the deficit in a more gradual three years). For the past five years, voters have routinely delivered Hudak low approval ratings, indicating that they never really trusted him enough to give the Ontario PC a chance at governing, even with a relatively limited minority mandate.

But the election results are also a defeat for radical ‘austerity’ politics. While Ontario’s voters may not particularly love the Liberals, especially after a decade of uninterrupted power, Wynne’s victory speaks to the fundamental moderation of Canadian and Ontarian politics. Hudak’s promises of deep cuts seemed incongruent with the state of Ontario’s finances — though the budget deficit is a concern, Ontario is by no means suffering a fiscal crisis. All three major parties have agreed for the need to reduce government spending, but Hudak’s Progressive Conservatives offered the kind of shock treatment that seems unnecessary for a generally efficient province like Ontario. McGuinty became truly unpopular in 2012 for some off the same reasons, suspending collective bargaining and pushing through new contracts with Ontario’s public school teachers designed to capture savings for Ontario’s finances, to the dismay of his voter base.

In contrast to both McGuinty and Hudak, Wynne offered a fiscal solution that more gradually slims public spending — essentially, holding provincial spending to zero increase over the next three years. The risk going forward is that Wynne, who has unmistakably pulled the Ontario Liberals leftward since winning the leadership in January 2013, won’t follow through on the deficit, especially after campaigning on such strong progressive rhetoric. A minority Liberal government, forced to negotiate with the NDP, would have been obligated to hold the line on fiscal discipline. Instead, Ontario’s voters will have to wait to see whether Wynne will prioritize deficit-cutting or progressive spending, as Adam Radwanski writes for The Globe and Mail:

It may take a little while, for both her and her supporters, for those realities to sink in. Ms. Wynne has vowed to reintroduce promptly the budget the Tories and NDP rejected to kick-start the election, which means she will get to make good on her promises to launch a new provincial pension plan, increase spending on social programs, invest in infrastructure, and try to stimulate economic growth through direct business investment….

Some of the voters who usually cast ballots for the NDP, and this time switched to the Liberals, might be a little easier to keep on board; there are ways, such as the new pension plan, to address their wishes without a major impact on the government’s bottom line. But if Ms. Wynne is serious about her fiscal targets in 2015-16 and beyond, those supporters might nevertheless start to wonder around the time of next year’s budget what they got themselves into.

In the coming leadership contest to replace Hudak, Ontario’s Progressive Conservatives will also have to think hard about what kind of party it wants to be. The party will have gone 19 years without winning an election by the time of the next one, presumably in 2018. Some leading Tories, like former cabinet minister Norm Sterling, have argued that the party will have to be ‘more progressive and less conservative.’

Possible contenders include deputy leader Christine Elliott (the widow of the former federal finance minister Jim Flaherty), former Ontario health minister Tony Clement, who currently serves as president of Canada’s Treasury Board, and rising star Lisa MacLeod, the 39-year old PC energy critic.

Horwath’s NDP also faces a tough future. It was Horwath who triggered the snap election by rejecting Wynne’s relatively progressive budget, a decision that seems incredibly short-sighted today. Horwath’s campaign was uneven by any standards, but especially considering that she presumably was in the best position to prepare for snap elections. Though the NDP holds as many seats today as it did before the election (21), many of its voters strategically abandoned Horwath to keep the Tories out of power, and the NDP now lacks the leverage over budget and other legislation that it held in the prior Legislative Assembly.

Extrapolating provincial trends to the national political scene is difficult, but the depth of the Liberal victory should give some hope to Justin Trudeau, the leader of the Liberal Party of Canada, in advance of next year’s federal elections. The Ontario Liberal win comes on the heels of the victories of the Parti libéral du Québec (Liberal Party, or PLQ) under Philippe Couillard in Québec’s April 2014 elections and the British Columbia Liberal Party under Christy Clark in BC’s May 2013 elections. In all three cases, provincial politics and policy issues drove the campaign. But three years after the disastrous performance of the federal Liberals under Michael Ignatieff, the Liberal victories in Canada’s three most populous provinces showcases the Liberal brand’s durability. What’s more, the Liberal provincial victories will give Trudeau limited optimism that he can hold off the Conservatives among Ontario’s moderate electorate, hold off the NDP in British Columbia, and limit the damage on his left flank from both the NDP and the sovereigntist Bloc québécois in Québec.

Much closer to home, the Ontario Liberal victory suggests good news for Olivia Chow’s Toronto mayoral bid — and bad news for her more conservative challengers, former Ontario PC leader John Tory and incumbent mayor Rob Ford, who’s currently on a leave of absence to seek treatment for substance abuse.

Though the mayoral race falls in October, and though it’s a non-partisan election, Chow, a former MP and widow of the late NDP leader Jack Layton, is the clear progressive candidate in the mayoral race. Though it’s typically a Liberal stronghold in provincial and federal elections, Torontonians supported the Liberals and the NDP over the Tories by a margin of 71.4% to 23.0%. Moreover, Ford’s former deputy mayor Doug Holyday lost his contest in the west Toronto riding of Etobicoke-Lakeshore, the suburbs that launched Ford’s own political career.

I’ve been using https://www.nothingbuthemp.net/products/relax-gummies ordinary for on the other side of a month for the time being, and I’m truly impressed by the absolute effects. They’ve helped me feel calmer, more balanced, and less anxious in every nook the day. My forty winks is deeper, I wake up refreshed, and sober my pinpoint has improved. The quality is famous, and I appreciate the natural ingredients. I’ll categorically carry on buying and recommending them to everyone I identify!