Just two months after Québec’s extraordinary election, which devastated the sovereigntist Parti québécois (PQ) and replaced the minority government of Pauline Marois with a federalist majority government under Philippe Couillard, Ontario voters will choose their own provincial government on Thursday in what has become a tight two-way race.![]()

![]()

Politics in Anglophone-majority Ontario, however, looks nothing like politics in Francophone-majority Québec.

As in most provinces, Ontario’s political parties have only informal ties to federal political parties. But Ontario’s political framework largely maps to the federal political scene. Accordingly, the center-left Liberal Party of Ontario is locked in a too-close-to-call fight with the center-right Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario (PC), with the progressive New Democratic Party of Ontario (NDP) trailing behind in third place.

All three parties have led provincial government the past 25 years. The Liberals are hoping to win their fourth consecutive election, after Dalton McGuinty won majority governments in 2003 and 2007 and a minority government in 2011. Under the leadership of popular former premier Mike Harris, the Progressive Conservatives won elections in 1995 and 1999. Bob Rae, formerly the interim leader of the Liberal Party of Canada, led an NDP government between 1990 and 1995.

ThreeHundredEight‘s current projection, a model based on recent polling data, gives the Liberals an edge over the Ontario PCs of just 37.3% to 36.5%, well within the margin of error. The Ontario NDP is wining 19.8% (though individual polls show that the Ontario NDP could win anywhere from 18% to 27% of the vote) and the Green Party of Ontario is winning 5.2%.

Voters elect all 107 members of Ontario’s unicameral Legislative Assembly in single-member ridings on a first-past-the-post basis. That, according to ThreeHundredEight, could result in anything from a Liberal majority government to, more likely, a hung parliament with either a Liberal or PC minority government.

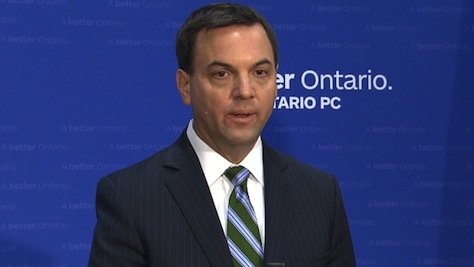

Though Toronto mayor Rob Ford may be more well-known internationally than either PC leader Tim Hudak (pictured avow, top) or Liberal leader and premier Kathleen Wynne (pictured above, bottom), the battle for Ontario could hold wider consequences across Canada. In some ways, it’s as close to a dress rehearsal for Canada’s expected federal elections in October 2015 as can be reasonably expected for a provincial election waged largely on provincial issues.

Though the Liberals are looking to win a fourth consecutive term, Wynne is leading them for the first time following her own leadership election in January 2013, something of an upset over the more moderate choice, Sandra Pupatello. Wynne, Ontario’s first female premier and Canada’s first openly LGBT premier in any province, has spent much of the campaign defending herself against charges from both Hudak and Ontario NDP leader Andrea Horwath.

The conservative challenge

Hudak, meanwhile, is waging his second campaign for premier after narrowly losing the October 2011 election to the Liberals. Ontario voters have had five years to become acquainted with Hudak, who won the PC leadership in 2009. Though his party initially led polls in advance of the 2011 election, McGuinty’s Liberals still managed to win that race. Though Hudak prevented McGuinty from winning another majority government, the Liberals fell short by just one seat. Similarly, before McGuinty announced his decision to step down as premier, Hudak’s PCs held a double-digit lead in polls as recently as December 2012.

Though Ontario voters may well deliver Hudak a long-awaited victory on Thursday, there’s a sense that they just haven’t warmed to him the same way that they did to Harris over a decade ago. Hudak’s platform emphasizes a rather hokey ‘Million Jobs Plan’ that promises his government would create a million new jobs in Ontario, despite challenges from economists that his plan greatly exaggerates his ability to do so. Hudak simultaneously pledges to roll back government bureaucracy, cut 100,000 public sector jobs and otherwise slash government spending. If the Liberal/NDP base was disappointed in McGuinty’s third-term budgets, they’ll be downright horrified by what a Hudak budget might entail.

Though polls show that Hudak has incredibly high unfavorable ratings in the province, polls also show that Ontario voters believe Hudak won the sole leaders’ debate on June 3. Ontario voters also tell pollsters that they believe it’s time for a change in government. So just as Canadian voters only hesitantly embraced Stephen Harper in 2006 at the federal level, Ontario voters might prove willing to give Hudak a provisional shot at governing with a minority mandate, which could dilute Hudak’s plans to cut spending at breakneck speed.

Wynne’s make-or-break moment

That the Liberals have a shot at winning a fourth term largely speaks to Wynne’s strength as leader and as premier. Though she might not have waged a flawless campaign, the Liberals almost certainly much more competitive under her leadership than they would have been under McGuinty, who left office 16 months ago unpopular with swing voters as well as with many Liberal activists, including unions and teachers upset with his decisions to suspend collective bargaining, force new change to contracts with Ontario’s teachers, and introduce wage freezes for public sector workers.

Ontario is Canada’s most populous province, home to 13.5 million of Canada’s 34.9 million-strong population, and its economy, employment and income levels largely parallel Canada’s national trends. Ontario is home to Ottawa, the Canadian federal capital, and Toronto, Ontario’s provincial capital, is the country’s financial center and arguably the cultural center of English-speaking Canada. By and large, Ontario’s government is a model for subnational governance on any standard, and it’s one of the most efficient, least corrupt and most accountable provincial governments in Canada, and that will almost certainly continue under either Wynne’s Liberals or Hudak’s PCs.

Among the most pressing issues of the campaign is the province’s $12.5 billion budget deficit, a gap that the Liberals and the NDP pledge to close in three years and that the Progressive Conservatives promise to close in two years. There’s no doubt that Hudak would wage a more aggressive campaign to enact budget cuts, but it’s hard to know exactly how disciplined a Liberal government would be, especially after Wynne’s leadership has tugged the party leftward. Though McGuinty showed himself willing to take on the vested interests in his own base to cut spending, he also presided over a massive increase in health care spending in his first term in office, paid for in part by a controversial increase in health care premiums for Ontario residents.

The path to fiscal solvency is clear enough, on the basis of a set of recommendations that McGuinty solicited from economist Don Drummond in 2012. Drummond’s report set forth a series of steps that Ontario’s government could take to forestall fiscal imbalances in the years ahead. But Hudak has arguably taken on board more of the substance of the Drummond report than Wynne’s government.

Will it all come down to the NDP?

Ironically, though the Ontario NDP has little chance of winning Thursday’s election, the result may come down to the NDP’s performance. It was Horwath’s decision not to support Wynne’s budget in May that ultimately led to the June snap election in the first place. But with such a tight race, NDP voters, as well as Green voters, may strategically support Liberal candidates in order to prevent the threat of a Hudak-led conservative government, especially in light of Horwath’s campaign, which has been more an indictment of Hudak’s plans and the McGuinty/Wynne legacy than any real plan for government. Wynne, over the weekend, has increasingly urged left-leaning voters of all stripes to unite behind her, a tactic that Horwath has dismissed as a fear campaign. No one is watching the Liberal/NDP dynamic in the Ontario election more than their federal counterparts, Liberal Party leader Justin Trudeau and NDP leader Thomas Mulcair, who might also find themselves battling over the anti-Tory vote in next year’s election.

That may not matter, because if, as widely expected, the result on Thursday is a hung parliament, Horwath and the NDP will almost certainly hold the balance of power. Back in 2011, McGuinty pledged not to form any coalitions, but rather to build legislative majorities on a vote-by-vote basis, a strategy that worked when the Ontario Liberals were already so close to a majority.

Horwath has tried to rule out the notion that she will align with either party, insisting that she is running for premier, not kingmaker. But she’s been more consistently resistant to forming a government with Hudak — earlier today, she called rumors of a PC-NDP coalition ‘bullspit.’

That doesn’t mean Horwath will work easily with Wynne, given that Horwath believes the Liberals failed to follow up on their promises to secure her support for the 2013 budget. But after the voting ends, Wynne and Horwath will find that they share much more in common on policy than they might have admitted on the campaign trail.

If so, there’s always a chance that Hudak and the Progressive Conservatives could win the election and still find themselves in opposition to a joint Liberal/NDP coalition government. Again, no one will have a keener interest in the post-election maneuvering than Trudeau and Mulcair, who might face a similar choice in 2015.

You ought to take part in a contest for one of the best websites on the internet.

I will highly recommend this website!

my web-site :: fashion [http://www.shopious.com]