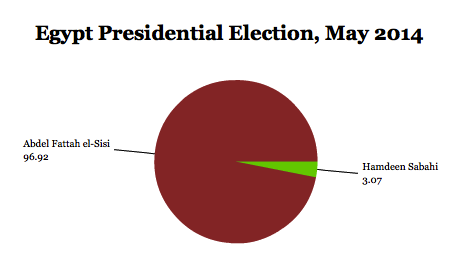

As the results come in from Egypt’s presidential election, here’s one thing to keep in mind about the extent of Abdel Fattah El-Sisi’s staggering margin of victory: ![]()

If his margin holds up in the final official results, el-Sisi will have won the election with a larger share of the vote than Egypt’s longtime strongman, Hosni Mubarak in both 1999 (93.79%) and 2005 (88.6%).

That’s all you really need to know about whether this was really a fair election — after months of pre-campaigning designed to paint el-Sisi as Egypt’s national savior and the military-led crackdown on journalists and dissent of all stripes, not just among the Muslim Brotherhood (الإخوان المسلمون) and supporters of former president Mohammed Morsi, who was deposed in July 2013 by el-Sisi, then in his capacity as army chief of staff and defense minister.

But if the margin is impressive, the turnout was not. Amid reports that just 7.5% of the electorate bothered to turn out in the two days in which polls were open, Egypt’s presidential election commission decided to allow voting for a third day, and the military government’s threats to fine non-voters helped boost turnout to around 47.3%, according to government reports (that may or may not be entirely accurate).

El-Sisi’s opponent, the secular leftist Hamdeen Sabahi, has already conceded defeat, but he also attacked the entire electoral process:

Sabahi also criticised what he called “not enough fairness and objectivity” from state institutions and media “choosing to mobilise people and not to make them aware.”

“We have chosen, with a full awareness of the challenges, to lead the battle. We did not run away from our duty of presenting the alternative that represents people’s dreams … digging a democratic path for the freedom of choice,” he said on the podium, followed by cheers and clapping from his supporters.

He saluted his campaigners, who he said proved they could do more than getting to the streets and competing, “even in unequal elections.”… “We were morally assassinated,” he said.

In Cairo, for example, which Sabahi carried in the 2012 election, despite his national third-place finish to Morsi and former Mubarak air force commander Ahmad Shafiq, Sabahi apparently won just 3.43% of the vote.

* * * * *

RELATED: How Egypt’s el-Sisi out-Nassered (and out Sabahi’ed) Sabahi

* * * * *

And yet, though the low turnout and the extra day of voting are something of an embarrassment to el-Sisi and the interim military regime, there’s a significantly large constituency that genuinely supports el-Sisi.

Though el-Sisi will undoubtedly share much in common with Mubarak, or even Egypt’s most famous 20th century leader, Gamal Abdel Nasser, he will come to office indicating that he will cut Egypt’s wasteful fuel subsidies, privatize what’s still a too-large public sector and otherwise cut the Egyptian budget in the hopes of boosting the country’s long-term growth. On the basis of remarks earlier this spring, el-Sisi seems set for a long-term program of austerity:

“Our economic circumstances, in all sincerity and with all understanding, are very, very difficult.” “I wonder, did anyone say that I will walk for a little bit to help my country?” “The country will not make progress by using words. It will make progress by working, and through perseverance, impartiality and altruism. Possibly one or two generations will [have to suffer] so that the remaining generations live.”

Given the significant economic component of the January 2011 protests in Tahrir Square that led to Mubarak’s ouster, however, and given that neither Egypt’s two subsequent military governments nor the Morsi administration have effectively addressed staggering youth unemployment or sclerotic GDP growth, it’s not clear that the Egypt people are willing to give el-Sisi one or two years to effect an economic turnaround, let alone one or two generations. So it will be fascinating to watch how Egypt’s economic policy unfolds in the months ahead.

In the meanwhile, Egypt’s revolution and its experiment with true democracy has come to an end. The Muslim Brotherhood, just 11 months of power, is today designated a terrorist organization, has fully reverted to its clandestine nature of earlier decades, with its top leaders imprisoned (or worse) in the increasingly authoritarian Arab state.