The European parliamentary elections have claimed their first national leader in Alfredo Pérez Rubalcaba, the general secretary of the Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE, Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party), Spain’s traditional center-left party.![]()

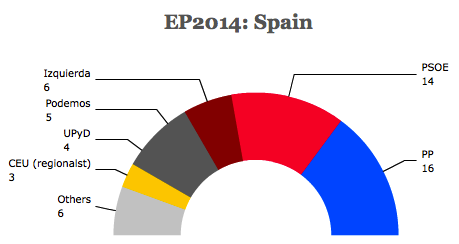

In Sunday’s elections, Spanish voters elected 54 members of the European Parliament. The ruling Partido Popular (the PP, or the People’s Party) of prime minister Mariano Rajoy won the largest share of the vote, around 26%, and the largest number of seats, 16.

The PSOE placed second with just 23% and 14 seats — that’s a loss of nine seats in the European Parliament.

Rubalcaba, taking the blame for his party’s losses, announced he would step down from the leadership, calling a meeting on July 19-20 to select a new general secretary of Spain’s largest center-left party:

“We have not managed to regain the trust of the citizens,” Mr Rubalcaba told a press conference in Madrid on Monday, adding that he would not stand for re-election at an extraordinary party conference in July. “We have to take political responsibility for the bad results, and this decision is absolutely mine,” he added.

There’s no guarantee that the next PSOE leader will be able to unite the Spanish left, which has fractured in the face of the economic crisis in the past five years.

The PSOE’s performance was hardly much worse than Rajoy’s party, which lost eight seats. Taken together, the two major Spanish parties won around 49% of the vote. That’s down from nearly 84% in the 2008 Spanish general election, 80% in the previous 2009 European elections and 73% in the 2011 general election.

So while the greater pressure fell on Rubalcaba and the PSOE, the results are hardly heartening for Rajoy.

Rajoy, at least, can argue that Spanish voters were punishing his government for two years of painful economic conditions. Unemployment in Spain is still around 26%, and the economy has contracted for four of the past five years. Rajoy’s government avoided a formal bailout from the European Union and the International Monetary Fund, but at a cost — Rajoy introduced nearly €15 billion in new budget cuts and other austerity measures, including a minimum wage freeze and income tax increases, upon taking office in December 2011. Rajoy’s efforts have helped stabilize Spanish bond yields and otherwise prevented further financial chaos in Spain, but the measures haven’t especially boosted economic growth.

Unfortunately for the PSOE, voters still want to punish it as well. Under former prime minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, the PSOE led Spain’s government between 2004 and 2011, presiding over Spain’s construction and credit boom in the mid-2000s. It was also Zapatero’s administration that launched the first painful attempts at austerity measures in the darkest days of the eurozone crisis.

Spanish leftward tilt hasn’t helped PSOE

If the PSOE’s fortunes are declining, it’s not because Spanish voters are rejecting the arguments of the left. The electorate has turned to even more leftist parties over the course of the last half-decade, largely at the PSOE’s expense, which is still as tainted with austerity as Rajoy’s PP.

A coalition of far-left parties, Izquierda Unida (United Left), which includes Spain’s traditional communist party, won 6.9% of the vote in the 2011 elections, and it won 10.0% of the vote in Sunday’s European elections, enough to win six seats in the European Parliament, its best result in 20 years.

A new anti-austerity group, Podemos, which translates to ‘We Can’, founded in February by academic Pablo Iglesias (pictured above), won 7.97%, enough for five seats, and it finished third in Madrid:

A pony-tailed professor of political sciences, Mr Iglesias is an outspoken critic of political elites in Spain and Europe, and their austerity-led response to the recent financial crisis. He has called for an end to the long era of dominance by Spain’s two established parties, and frequently takes aim at the German government, which is seen by many in Spain as the true architect of recent economic policy in the crisis-hit countries of southern Europe.

The five Podemos deputies say they will join the leftwing bloc in the European Parliament led by Alexis Tsipras, the leader of Greece’s Syriza party. “From tomorrow, we will work together with other partners from southern Europe to say that we don’t want to be a colony of Germany and the troika,” Mr Iglesias told supporters on Sunday night.

In Catalunya, the leftist and pro-independence Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC, Republican Left of Catalunya) continued to assert its dominance, winning more votes than the more conservative separatist Convergència i Unió (CiU, Convergence and Union). Though CiU is currently the largest party, and its leader Artur Mas is the Catalan regional president, it’s been forced to rely on the ERC to govern since the November 2012 snap regional elections. Both parties support a planned November 9 referendum on Catalan sovereignty, a gambit that Rajoy has declared unconstitutional. On Sunday, the ERC won around 23.7% of the vote, with CiU winning just 21.9%.

Rubalcaba, who led the PSOE to defeat in the 2011 national elections, has struggled in his three years leading the party in opposition. As interior minister for five years and, briefly, deputy prime minister in the Zapatero era, Rubalcaba was hardly the best choice to lead the party out of the political wilderness. No one has accused him of having a charisma surplus, and he’s struggled to articulate a coherent economic policy, given that the Rajoy government’s austerity policies picked up where Zapatero’s left off. Rubalcaba has also had a difficult time staking out a position in the polarized battle between Rajoy’s central government and Mas’s regional government in Catalunya on sovereignty. Rubalcaba refused to endorse the Catalan referendum, despite a mutiny from local Catalan Socialists over the issue. That’s one reason that Catalan leftists are turning increasingly to the ERC, and away from the PSOE.

Chacón, López, Madina and Díaz could all vie for leadership

The immediate frontrunner to succeed Rubalcaba is expected to be Carme Chacón (pictured above), a former defense minister in the Zapatero government. She’s already called for open primaries to determine the next PSOE general secretary, and she’ll almost certainly run for the position. Chacón narrowly lost a leadership bid to Rubalcaba in February 2012 following the PSOE’s disastrous 2011 election defeat. At age 43, and back in Spain after a year teaching at the University of Miami, she might be able to connect with younger voters, who face staggeringly high unemployment, and who flocked in high numbers to the UI and to Podemos in Sunday’s elections. Chacón is also Catalan, so she might be able to convince ERC supporters to give the PSOE a fresh look — if she can articulate a coherent PSOE policy on Catalan nationalism.

The immediate frontrunner to succeed Rubalcaba is expected to be Carme Chacón (pictured above), a former defense minister in the Zapatero government. She’s already called for open primaries to determine the next PSOE general secretary, and she’ll almost certainly run for the position. Chacón narrowly lost a leadership bid to Rubalcaba in February 2012 following the PSOE’s disastrous 2011 election defeat. At age 43, and back in Spain after a year teaching at the University of Miami, she might be able to connect with younger voters, who face staggeringly high unemployment, and who flocked in high numbers to the UI and to Podemos in Sunday’s elections. Chacón is also Catalan, so she might be able to convince ERC supporters to give the PSOE a fresh look — if she can articulate a coherent PSOE policy on Catalan nationalism.

Patxi López (pictured above), age 54, who served as the lehendakari, or regional president, of the Basque Country between 2009 and 2012, has, like Chacón, been a prominent voice for change within the PSOE. But if he seeks the national leadership, he may have a hard time making the case that he can restore the PSOE’s fortunes after he led the local Basque Socialists to a third-place finish in the October 2012 regional elections.

Eduardo Madina (pictured above), age 38, is another Basque Socialist, who has served as the secretary-general of the Congreso de los Diputados (Congress of Deputies), the lower house of the Spanish legislature. Unlike Chácon, he would mark an even greater rupture from the Zapatero era and a clean break from the Rubalcaba-Chácon leadership fight two years ago. He’s a popular figure throughout the country, and he has the added credibility of having survived a terrorist attack in 2002 when a car bomb planted by the Basque nationalist ETA destroyed part of his left leg.

Another less likely contender is the regional president of Andalusia, Susana Díaz (pictured above), age 39, who took power in September of last year, representing a generational and conceptual pivot from the region’s old-guard Socialist leaders, Manuel Chaves and José Antonio Griñán. Though Díaz may not run for the national leadership, she’s becoming an increasingly popular figure both in Andalusia and nationally.

Igelsias photo credit to ETA.