There’s not a lot of doubt about the outcome of Egypt’s May 26-27 presidential elections.![]()

Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi, the former army chief and defense minister who orchestrated the coup that toppled Islamist president Mohammed Morsi in July 2013, is the wide frontrunner in what will be the eighth national election — including constitution referenda and presidential and parliamentary elections — since the fall of former Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak in February 2011.

While there’s plenty of time to speculate about how el-Sisi will govern Egypt as its ‘civilian’ president, he still faces nominal opposition in the form of his only challenger, Hamdeen Sabahi.

Back in May 2012, Sabahi quite nearly made his way into the presidential runoff, and he actually won the greatest share of the vote in Cairo, the Egyptian capital. Though no one expected him to emerge as a major candidate, he slowly became a leading player in the campaign.

Unlike Morsi, he was a secular candidate, so there would be no risk that Sabahi would have turned Egypt over to the Muslim Brotherhood (الإخوان المسلمون), which largely happened once Morsi eventually won the president and took office.

Unlike Ahmed Shafiq, who unsuccessfully faced off against Morsi in the June 2012 runoff, Sabahi never served in the Mubarak administration, and so couldn’t be counted among the felool — or remnants — of the old regime. Rather, Sabahi was as a liberal activist and Mubarak critic in the 1990s and 2000s. During the Tahrir protests, he was on the front lines, urging Mubarak’s fall.

But more fundamentally, Sabahi seemed to capture the kind of nationalist spirit most often associated with Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt’s internationally renowned president in the 1950s. Like Nasser, Sabahi is a nationalist and a leftist and Sabahi campaigned on a ‘neo-Nasserite’ platform that included a fiercely independent Egyptian foreign policy and programs to alleviate poverty and unemployment. Though Egypt remains the world’s largest Arab country, it’s no longer the cultural, financial and political engine of the Arab world that it was during the Nasser era, but Sabahi’s 2012 campaign tapped into the same sense of Egyptian pride in the same way as the 2011 revolution centered in Cairo’s Tahrir Square, which culminated with the fall of Mubarak’s 30-year regime.

There’s almost no doubt that in a runoff against either Morsi or Shafiq, Sabahi would have easily won the presidency. Ultimately, Morsi won 24.8%, Shafiq won 23.7%, and Sabahi won just 20.7%, leaving Egyptians with a gruesome choice between a Muslim Brotherhood lackey and a Mubarak-era air force general.

Sabahi, like many liberals, reluctantly endorsed Morsi. Also like many liberals, he initially supported military intervention against the Morsi administration in June 2013, with Morsi and his Brotherhood allies pushing the boundaries of Egyptian democracy and constitutionalism.

Unfortunately for Sabahi, he isn’t the Nasser of the 2014 presidential election.

Sabahi isn’t even the ‘Sabahi’ of the race anymore.

That’s el-Sisi.

El-Sisi has made it clear that he’ll implement an economic program that features much budget austerity than Nasser-era socialism. To the extent there’s a major policy difference between El-Sisi and Sabahi, expect El-Sisi to phase out popular fuel subsidies and otherwise push through painful cuts and privatization measures. Expect Sabahi, if he somehow wins, to double-down on expanding employment through the public sector and other public works programs.

Furthermore, in a world where Egyptian-Israeli peace has been a fact of Middle Eastern life since the 1970s, and with no Suez Crisis to rally the Arab world, it’s difficult to imagine el-Sisi ever rising to anywhere near the same level of pan-Arab adulation as Nasser once achieved.

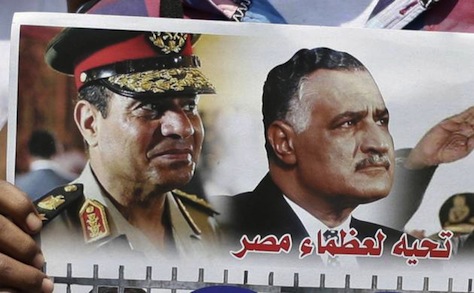

But on almost every other measure, el-Sisi is doing a strong impersonation — the promise of strong leadership, the charismatic style, the military background, the personality cult, the disdain for democracy. He has even compared himself publicly to Nasser, and supporters don’t hesitate to make the connection, either. Nasser’s eldest daughter, Hoda abdel Nasser, and Nasser’s son, Abdel Hakim Abdel Nasser, a former Sabahi supporter, have now both endorsed el-Sisi.

Consider this. Nasser played a behind-the-scenes role in the 1952 revolution that overthrew Egypt’s monarchy. Nasser eventually clashed with the post-revolutionary president, Muhammad Naguib, placing him under house arrest. After a member of the Muslim Brotherhood attempted to assassinate Nasser in 1954, he effected a harsh crackdown against the Brotherhood. By 1956, at the height of his popularity, he formally assumed the Egyptian presidency — and he held it until his death 14 years later.

It’s not a perfect analogy, of course, but you could be forgiven for believing that el-Sisi’s maneuvering since July 2013 (or even before) comes directly from the Nasser playbook. He’s protégé of Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, who served as Egypt’s army chief and defense minister from 1991 through more than a decade of the Mubarak era, through the intermediate period of rule by the Supreme Council of Armed Forces (SCAF) and for the first couple of months of the Morsi administration, until Morsi forced Tantawi out — in favor of el-Sisi.

As protests against Morsi’s unpopular administration mounted in June 2013, el-Sisi led the military coup that ousted Morsi, placed him and other top Muslim Brotherhood officials under arrest, and over the past 11 months, effected a brutal and often lethal crackdown against the Muslim Brotherhood (and other ‘terrorists’ in the eyes of the military regime). He then oversaw a comically lopsided ‘referendum’ to revise Egypt’s constitution on lines that eliminated Morsi-era changes, jailing or otherwise silencing critics in a process that ‘won’ 98.13% of the vote.

* * * * *

RELATED: Egyptian massacre, ‘state of emergency,’ mocks Arab spring with return to Mubarak-era tactics

* * * * *

As Egyptians prepare to vote early next week, the field of potential candidates has been so cowed that no one, excepting Sabahi, was even willing to participate in a race tailored for el-Sisi to win once the official campaign began in April, itself preceded by an unofficial months-long campaign designed to maximize el-Sisi’s appeal. The Salafist Al-Nour Party (حزب النور), once the chief Islamist competitors to the Muslim Brotherhood, is backing el-Sisi. The New Wafd Party (حزب الوفد الجديد), the leading Egyptian liberal nationalist, is also supporting el-Sisi, as are most of the leading members of the Tamarod (تـمـرد) movement that formed in protest of the Morsi administration in June 2013.

Though I’ve described el-Sisi’s gradual consolidation of power, which will climax with his victory in the presidential race next week as Egypt’s ‘re-Mubarakification,’ el-Sisi’s accent rises beyond the level of Mubarak-era control. At least in the Mubarak era, there were competing factions — a more statist group tied to the armed force and other Egyptian institutions, and a more liberal group unofficially led by Mubarak’s son Gamal. The el-Sisi era could find Egyptian power even more concentrated at the top.

As Ursula Lindsey eloquently wrote for The Arabist earlier this month:

One shouldn’t under-estimate the appeal of his displays of emotion or his paternalism (two sides of the same coin). Many Egyptians are waiting for a strong man to “take the country in hand”; they won’t bristle at the way he amalgamates the army and the state to his own person (rhetorically telling protesters and strikers: “I don’t have anything to give you!”, as if the country’s budget and his own bank account were one and the same). But it is hard to gauge the field marshall’s true level of support when the entire transitional period has been aggressively engineered to ensure his candidacy an aura of inevitability.

Both Sadat and Mubarak stumbled into their jobs. El Sisi is coming to the position as a savior. This is a man who doesn’t just want to be obeyed; he insists on being loved. This is a man who thinks he’s the smartest guy in the room (with some cause: he has outwitted all his adversaries over the last few years).

So what’s Sabahi to do? And why is he even still bothering to campaign against such long odds?

In one sense, Sabahi, too, is facilitating el-Sisi’s by lending him the credibility of a serious challenger.

But Sabahi is also laying a marker. In the el-Sisi era, to the extent that opposition will even be allowed to flourish, Sabahi will become the leading liberal critic of the new administration, and that will count for at least something. If, somehow, el-Sisi falls flat in the next four years, Sabahi will be a familiar face to whom either the military, Egypt’s business elite or even a future Egyptian electorate might turn. So there are clear advantages to Sabahi’s David-versus-Goliath fight.