More than a month after Indonesia’s parliamentary elections, and with just less than two months until its presidential election, all eyes are on Jakarta governor Joko Widodo (most Indonesians refer to him simply as ‘Jokowi’), the frontrunner to become Indonesia’s next president. In particular, many Indonesians are watching to see who he will choose as his running mate in the July 9 vote. ![]()

Under Indonesia’s somewhat arcane system, a party (or a coalition of parties) must win either 25% of the national vote in the April parliamentary elections or hold 20% of the seats in the Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat (DPR, People’s Representative Council) in order to nominate a presidential candidate.

No single party — not even Jokowi’s — managed to surpass that hurdle. That’s led to a series of behind-the-scenes negotiations among Indonesia’s major parties to sort alliances for the July election. It makes for a uniquely Indonesian version of ‘veepstakes,’ a term normally applied to the drawn-out process whereby US presidential nominees painstakingly select a running mate. Just as in the United States, the Indonesian media is watching Jokowi’s every move this week to divine clues as to his choice.

* * * * *

RELATED: ‘Jokowi effect’ falls flat for PDI-P in Indonesia

RELATED: Who is Joko Widodo?

* * * * *

Among the more tantalizing names being floated is Jusuf Kalla (pictured above), who served as vice president in the first term of the outgoing incumbent, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, and who currently serves as president of the Indonesian Red Cross Society.

Final results from the election were announced late last week, and the presidential candidates have until May 18 to name their running mates, a decision that usually bridges two or more parties in alliance for the presidential elections. Jokowi is set to announce his own running mate on Friday.

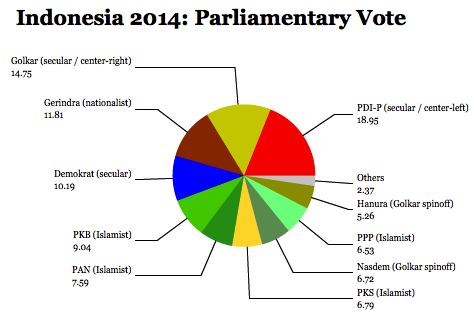

His party, the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P, Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan), emerged with 18.95% of the vote, well below of the 25% mark — that result was somewhat of a disappointment for the party, which had hoped its formal announcement that Jokowi would lead its presidential ticket would boost its parliamentary support to 30% or higher.

That, in turn, means that Jokowi, like Yudhoyono before him, will have to seek out a broad, multi-party coalition, potentially limiting the depth of economic and other policy that his administration might be able to pursue.

The PDI-P already has the backing of two small parties, Surya Paloh’s secular Nasdem (Partai Nasdem), which won around 7% of the parliamentary vote, and the Partai Kebangkitan Bangsa (PKB, National Awakening Party), which won around 9% of the national vote, making it the most successful of the four major Islamist parties in the April legislative vote. The PKB has strong ties to Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), a Sunni Islam group founded in 1926 that has traditionally played an important cultural and political role, and it’s the party of former president, Abdurrahman Wahid (also known as Gus Dur), who governed between 1999 and 2001 in alliance with the PDI-P.

Jokowi’s decision will come in coordination with both Nasdem and the PKB, as well as Megawati Sukarnoputri, who served as Indonesia’s president between 2001 and 2004, and who is the daughter of Indonesia’s first post-colonial president, Sukarno. As the leader of Indonesia’s main opposition party, Megawati tried, unsuccessfully to win the presidency in both 2004 and 2009. Until the announcement that Jokowi would lead the PDI-P ticket nearly a week before the parliamentary elections, Megawati was believed to be considering another run this year. Megawati remains incredibly influential within the party and she will almost certainly play a major role if Jokowi wins the presidency.

Though the PDI-P, together with its allies, has amassed a coalition that has won a cumulative 34.7% of the parliamentary vote, it’s expected that Jokowi will ally with one of the other major Indonesian parties.

Jokowi’s most formidable challenger, Prabowo Subianto, is waging a strenuous campaign against Jokowi, criticizing the frontrunner’s youth and lack of experience and espousing a platform of economic nationalism and protectionism with respect to Indonesia’s mineral resources. Though Megawati ran in 2009 on a ticket with Prabowo, he seems to have the best chance against Jokowi. Prabowo’s party, Gerindra (Partai Gerakan Indonesia Raya, the Great Indonesia Movement Party) surged into third place in the parliamentary elections, with nearly 12% of the vote, and it’s already formed an alliance with United Development Party (Partai Persatuan Pembangunan, PPP), another minor Islamist party that won around 6.5%.

Kalla, the man who could return to the vice presidency, belongs to Golkar (Partai Golongan Karya, Party of the Functional Groups), the party that governed Indonesia from 1967 to 1998 under Suharto’s one-party rule. If Golkar and the PDI-P join forces, it would mark a historic union of two one-time rivals, Sukarno and Suharto.

Kalla’s support would bring with it Golkar’s party machinery. Kalla, personally, is popular in Sulawesi, thereby balancing Jokowi, whose base is in Java — notably, in Jakarta, where he’s served as governor since 2012, and in Surakarta (Solo), where he previously served as mayor. Kalla, at age 71, is nearly 20 years older than Jokowi, a relative newcomer to national Indonesian politics, and Kalla could insulate Jokowi against charges of inexperience. As a member of the NU, Kalla’s candidacy would meet favorably with PKB and Islamist voters, too.

But Kalla is a wily politician, and he represents some of the most ossified interests in Indonesian society. When he first served as vice president, Golkar was the largest party in the Indonesian legislature. Though Yudhoyono won a strong presidential mandate in 2004, Kalla arguably became the more important person in Indonesia’s government because he had a greater support base in the Indonesian legislature. Not surprisingly, the two clashed over policy and politics, and Kalla ultimately ran against him in the 2009 election (he placed third with just 13% of the vote, behind Yudhoyono and Megawati). If he’s elected as vice president again, there’s a risk that he could similarly outmaneuver Jokowi.

Another open question is whether Golkar would still field a presidential candidate in the event that Kalla runs with Jokowi. Though Kalla is a former Golkar party leader, its current leader, businessman Aburizal Bakrie is running for president, though he seems to be far less popular than Jokowi and Prabowo. If he doesn’t agree to pull out of the race in favor of a Jokowi-Kalla ticket, it could split Golkar’s ranks. A meeting between Prabowo and Aburizal last week only added more mystery to the issue in advance of a Golkar executive meeting scheduled for later this month.

Another option is to ally with Yudhoyono’s governing party, the Partai Demokrat (Democratic Party), which won just 10% of the vote. It currently has no incredibly strong presidential contender, and it risks becoming irrelevant once Yudhoyono, its founder and leader, leaves the presidency after a somewhat mixed decade in office. Becoming the junior partner in a Jokowi-led administration might be the most viable way to secure its future.

Among the other figures being suggested as potential Jokowi running mates are Ryamizard Ryacudu, Indonesia’s former army chief of staff, former constitutional court chief justice Mohammad Mahfud, a member of the PKB, and Corruption Eradication Commission chair Abraham Samad.